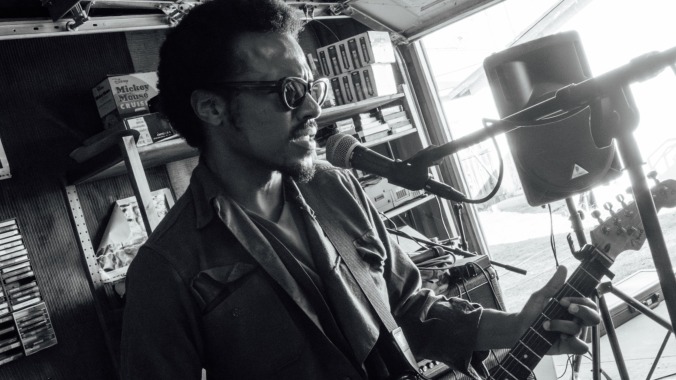

Benjamin Booker, Beyond Recognition

The New Orleans singer, songwriter and producer sat down with Paste to discuss the life-affirming powers of Kerry James Marshall’s art, his intercontinental collaborations with Kenny Segal and his first album in seven years, LOWER.

Photo by Trenity Thomas

In the diasporic religion of Haitian, Dominican and Louisiana vodou/voodoo, there are spirits called lwa that speak to humans in dreams and divinity. There are Petwo and Rada lwa, meant to symbolize something transcendent, something akin to saints in Roman Catholicism. They live beneath bodies of water, at the bottom of seas and rivers. The lwa are intermediaries between a supreme creator god and humanity, offering humans protection, healing and wisdom through possession in exchange for ritual sacrifice and ceremony. Every lwa is unique, understood through colors, days of the week and talismans. Vodouists say they are easily angered, but can be very loyal if devoted to correctly. Deriving from the Yoruba language in Niger-Congo, and phonetically identical in French and Creole, “lwa” sounds like “lower,” if it rolls off your tongue just right. In a street of blood, a lwa arrives by fire at night; “I want the world,” Benjamin Booker sings on his new record, LOWER. “I wanna live a good life.”

At the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles in 2017, Booker visited a Kerry James Marshall retrospective. Marshall’s penchant comes from making art derived from this phrase in Paul Garon’s book Blues and the Poetic Spirit: “Magic is evoked when frustration threatens desire.” He named one of his paintings after it, intrigued by voodoo symbolism, levitation and the Black experience in the United States, how Black people blended Western and African traditions. His work is cabalistic and magical, a tradition as vivid as it is folkloric and referential. He once said of the works of Constantin Brâncuși, Sam Doyle, Bill Trayler and Giotto, “It’s all material that can be combined to make something that nobody’s seen before.” All of the change in Booker’s life, he says, can be attributed to seeing Marshall’s exhibit. He wanted to “live that kind of life,” a life of magic and purpose.

“It’s all material that can be combined to make something that nobody’s seen before” is synthesized into an album like LOWER, Booker’s attempt at patching incongruous elements into something ridiculous—at making something in-between the divine and the ordinary. There was no blueprint, but the directions of Mobb Deep’s Hell on Earth and the Jesus and Mary Chain’s Psychocandy lingered nearby. “I realized that the combination of heavily distorted sounds mixed with boom-bap hip-hop does not exist,” Booker says. “You can’t find that. I remember telling the guy who ran my management company, I showed him a song and he was like, ‘I like this song.’ And I was like, ‘I think I’m going to throw some distorted guitar and boom-bap drums on it,’ and he laughed. I was like, ‘Yes, exactly.’ The idea of it just sounded ridiculous.” Once he made “LWA IN THE TRAILER PARK,” Booker had finally made the thing he’d wanted to hear for himself and no one else.

Back when I was still a Pandora Radio stumper in 2014, I discovered Benjamin Booker’s work through the shuffle of a rock station—I want to say it was Cage the Elephant Radio, or something of the like. I owe a lot to Pandora, admittedly; I wouldn’t have heard Frank Ocean’s “Pyramids” for the first time without it. It was good for algorithmic discovery, and it felt much more spectacular back then. The auto-play feature on Spotify and Apple Music just don’t hit like that nowadays. But Pandora pointed me towards a song of Booker’s, “Violent Shiver.” I was hooked immediately, sucked into the god-fearing, guitar-toting explosions like it was this feverish, irresistible tractor beam. This was my taste at the peak of its “loud guitars” era. Booker had this aura about him, punched into view thanks to his raspy, shredded howl. He just had a way of playing that pulled something out of me. 11 years on and I still can’t quite put a finger on what.

Booker used to go around interviewing funeral home directors in Gainesville, where he was studying journalism at the University of Florida. He had a knack for talking with people. It was, more than a decade ago now, a big reason he kicked up a music career—talking to people about their craft, it became a holistic, mutually-gainful vocation. Booker found his bag: interviewing punk bands, especially his favorite band (at least once upon a time), No Age. Around 2012, after getting some sage advice from Chuck Klosterman, he began writing his own music, bringing “Wicked Waters” and “Have You Seen My Son” to life, along with “Spoon Out My Eyeballs” and, yes, “Violet Shiver.” He signed with the great ATO Records, joining the likes of Hurray for the Riff Raff and Margaret Glaspy, and the story goes that Jon Salter signed Booker after watching the Tampa-bread picker play a half-hour gig.

I liked Booker’s early material because I’d grown up listening to Motown, Wilson Pickett, Otis Redding and Booker T. & the MGs. I also liked Booker’s early material because, at age 16, I was starting to get stoked on punk music. Those worlds collided like gold on Benjamin Booker, a record so money it landed him at Coachella, Bonnaroo, Governor’s Ball, Primavera Sound, and on bills with Parquet Courts, Courtney Barnett and Bully. When Jack White went on his Lazaretto Tour, he brought Booker along with him. Few rock musicians were as interesting 10 years ago as Booker was.

His stardom rose so high he got Mavis Staples on a joint with him two years later. In fact, his entire sophomore album—Witness—was special, vaulting him into a reputation so meteoric that he was tapped as the opening act for three Neil Young gigs in the Midwest. And Witness feels as miraculous now as it did the first time I heard it. The title track and “Believe” arrived as these full-bodied ensemble pieces, dappled with string sections and vibrato pitch shifts. It was a gesture of change for Booker, who’d graduated from angular, bluesy tones and turned towards politicking, envelope-pushing gospel music. The move may have angered some of Booker’s faithful audience, and Witness may sound lifetimes away from LOWER, but the two records share a similar sense of defiance and social commentary.

But, of course, Booker all but disappeared by the end of the 2010s. His career went radio-silent. All we had were the two LPs and the self-released Waiting Ones EP, and I devoured them over and over and over again. After Witness came out, Booker gave himself permission to explore and see what he liked. He became more precious with his guitar, feeling “less tethered to riffs and playing notes” and becoming more interested in using the instrument as a way to articulate a feeling than as a weapon of garage-rock revivalism. “I was trying to get to something else,” he says. “When I first started playing music, it was the first 12 songs I had ever written. I didn’t think past one record, so when it came to do the second one, it felt like a very transitional record—where it was like, ‘I don’t know what I’m going to do, but I want to do something else.’” Booker, like a lot of us, had been using blogs to build out his own taste, but he wanted something more—he wanted to find the pockets that music journalists weren’t writing about. So he did the work, spending hours combing through African and Brazilian records, Chicago footwork and European ambient.

When he made his debut album, Booker says that he had a clear, literal vision of what he wanted it to be. He remembers fixating on this split-second image of him playing on a stage with the exact vibe the songs wound up catering to. But once the time came to make Witness, Booker didn’t know where to go. “I was lucky,” he admits. “I had songs that I felt were strong but, stylistically, I was trying to find something more.” You can hear elements of LOWER on that record, especially during “Witness,” which flashes glimpses of this Tribe Called Quest, boom-bap style mixed with a crushing, fuzzy, melodiless soundscape.

But seven years ago, those ideas didn’t feel nearly as realized as they do now. “I just wanted to write songs that I felt represented me in some way, that I enjoyed listening to and enjoyed playing,” Booker says. Plus, there was pressure on him detouring towards a style of music that was “safe” to make—from suit-type people, as he puts it. “I had to get away from all of those things. I couldn’t have survived in that world, and it had only just begun to happen.” He got to do what he wanted on Benjamin Booker and Witness, he clarifies, but he could see what was waiting for him. “It was like, ‘Oh, my God, this is only going to get way worse. And I don’t want to be in this at all.’”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-