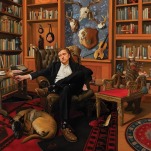

Biffy Clyro Looks Beyond Rock

It may come as a surprise that three bare-chested, tattoo-covered, hard rockers who have shared the stage together since their teens, tearing through sweat-soaked clubs, arenas and even stadiums, have two distinct fears. The first was of a small vacant room.

“We’ve always been a little bit afraid of the studio and we’ve always used it as a way just to document the sound of our band,” says 36-year-old Biffy Clyro singer-guitarist Simon Neil.

While Neil and the Johnston brothers—James (bass) and Ben (drums)—trust their instruments, the synths and various sound manipulators, with their knobs and switches, have always made them uncomfortable. That’s why on their seventh album, Ellipsis, they naturally went in that direction to overcome the obstacle.

The second fear is harder to overcome, and has Neil envisioning a best-case scenario of the band’s native Scotland separated from the United Kingdom and a member of the European Union or Scandinavia.

Brexit is “the worst decision that [the U.K.] has ever made apart from enslaving the entire globe hundreds of years ago. The politicians have lied to the purest people and the least educated people. It’s not fucking fair. I’m so incredibly angry and it’s really a depressing thing,” he says.

While Scotland has hope, England is screwed, he adds. The government has fallen apart and the politicians have fled the nest.

“David Cameron is a chickenshit. He just walked off. And you’ve got [U.K. Independence Party leader] Nigel Farage and [London mayor] Boris Johnson…All old, white men. All going to be dead by the time it impacts the future generations.”

Scotland voted definitively for the U.K. to remain in the European Union. The country’s votes didn’t make any difference. Until Brexit, Neil could never imagine fear winning over a nation. Now he has a message to the United States: “I now have a genuine fear for the world and it makes me think anything’s possible. I plead with you all, just keep Trump the fuck out!”

Simon Neil isn’t bashful with his words, and Biffy Clyro isn’t a traditional metal or post-rock band. They’ve explored other sounds in the past. On 2013 double album Opposites, they incorporated strings, church organs, a mariachi band and even tap dancers. But until now, those sounds had always been organic, made by running a hand across guitar strings, the stomping of feet, air passing through brass—never the push of buttons.

“We wanted to explore the tricks that [the studio] held,” he says. “Most rock bands still aspire to make records that sound like records by Black Sabbath or Led Zeppelin. The fact is these albums were 40, 50 years ago. I want us to evolve into something beyond just guitar, bass and drums.”

Approaching the band’s seventh album, Biffy Clyro didn’t want to lose their sense of discovery and adventure. They didn’t want to become stale. The trio’s first three, independent records were in the progressive metal mold, where they stuck every crazy idea in to a song they could think of. Their most recent three albums, including Opposites, were bigger, bolder statements with full orchestration. They were Biffy’s statement on arena rock.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-