Music So Loud, Can’t Tell a Thing: Big Star’s Radio City at 50

A half-century later, the Memphis band's sophomore album remains a bright, beautiful portrait of young, big emotions and the way they intersected with the joy of music.

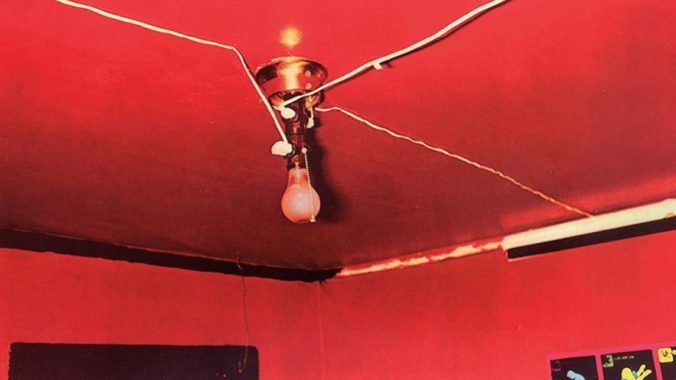

Photo by William Eggleston

Radio City begins with a guitar revving its engines, a slide that starts things up and never stops. Big Star’s 1974 sophomore album, which turned 50 this month, clears its throat with “O, My Soul,” a surfy, funky jaunt that’s the rock and roll equivalent of all of the lights flickering on at an arcade. “Go ahead and shake if you wanna,” sang Alex Chilton, then 23-years-old, having already learned how to shake, rattle and roll as the teenybopper frontman of The Box Tops. With that whirling organ part and Jody Stephens’ raucous, choppy drumming, the album’s opener finds Chilton trying to strut his stuff, projecting confidence to mixed success. “When we’re together, I feel like a boss,” he admits. “O, My Soul” chronicles a search for the transformative properties of pop—a lover, a hit song or a car—because Chilton was always in search of music’s catharsis.

In 1970, Chilton returned to Memphis, recently having left the Box Tops, best known for the late ‘60s hit “The Letter.” Local vocalist/guitarist Chris Bell invited Chilton to join, alongside drummer Stephens and bassist Andy Hummel, and form Big Star. The group toiled over their debut, #1 Record, sweating out 12-string acoustic guitar melodies and crisp harmonies at Ardent Studios. Chilton and Bell fancied themselves as a Lennon–McCartney-esque duo, producing meticulous pairings of T. Rex-like swagger and strict, Beatles-y arrangements. #1 Record was distributed and promoted poorly by Stax Records, leading Bell to quit the band after copious infighting—and Big Star eventually disbanded for a few months, only to reform and eventually get back to work at Ardent on Radio City, an album that became one of power pop’s ur-texts.

Just before Bell began work on the aching, heartbroken “I Am The Cosmos” and similar solo material, Chilton took the reins of the band. But the influence of Bell, “[Chilton’s] folkie counterpart” as Robert Christgau described him, still rears its head here. Bell wrote much of Radio City’s “Back of a Car,” a teenage fantasy about driving around, listening to music and not knowing how to say you love someone. Along with “I’m in Love with a Girl,” a rare, earnest tangent from Chilton, “Back of a Car” remains one of Radio City’s most hopeful songs. The band choreographs the track wondrously, centering the verses around Chilton’s struggle to admit his feelings. A soaring harmony and accented drums force him to spit out the sentiment, with the line “I love you, too” simply concluding the chorus.

Without Bell’s contrasting, direct sensitivity, Chilton’s songwriting reoriented towards confusion. He began writing harsher, more vicious sentiments while largely retaining the ringing guitars and Hummel’s hooky basslines of their debut. The production, covered primarily by the band, themselves, provides a throughline between Radio City and Big Star’s debut. But songs like “What’s Going Ahn,” most memorable for its moody Wurlitzer chords and airy, haunting “ooh’s,” pinpoint Chilton’s new indifference and uncertainty. “I like love but I don’t know / All these girls, they come and go,” he sings, offering a broad overview of Radio City’s diminished spirits.

Naturally, Chilton wasn’t content. He was forced to grow up quickly while on tour with the Box Tops, which came after having a #1 hit with them at just 16 years old. What remained was the acute resentment that fuels a song like “Life is White,” full of petty, selfish squabbles and chunking guitars that sync up with a wailing harmonica. “I know what you lack / And I can’t go back to that,” sings Chilton, before the band wanders towards a honky-tonk piano break. The result is blistering bubblegum, a precursor to the meanness of Bob Dylan’s “Idiot Wind” if it were made up of oversimplified feelings and Byrds guitar tones. While Chilton’s childishness isn’t always the easiest pill to swallow, “Life is White” understands the corrosive nature of apathy in a relationship.

Stephens’ drumming throughout Radio City surprises for how choppy or ambling it can be, a welcome disruption to pop rock’s normally perfunctory drummers. After three strikes of a snare drum on “Daisy Glaze,” the simmering resentment of “Life is White” erupts into an undercurrent of violence. The song begins woozy and dejected, Chilton’s discombobulating delivery staggers along with Stephens’ cymbal crashes, but suddenly the tempo shifts and the guitar leads are harmonized and bending. Everything ends in a frenzy, with Chilton singing arriving at a bar, looking to score, and getting ready to fight on the dance floor. In the album’s most crass, sexist moment, Chilton belts “Who is this whore?,” chastising his company before growing existential. As guitars ricochet higher and higher up the scale, “Daisy Glaze” is Chilton lashing out, tossing blame around for his lasting emptiness that informs Radio City.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-