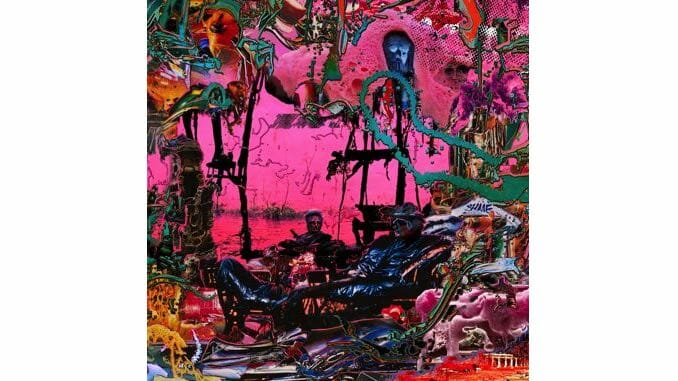

black midi Take You to Hell and Back on Their Thrilling Joyride Hellfire

The London band’s third album is a grotesque carnival of human misery that you’ll never want to turn away from

It’s difficult to describe exactly the way listening to black midi makes me feel. It’s even trickier to describe exactly what they sound like in general. Despite taking influence from progressive, avant-garde acts like Captain Beefheart, Primus and Frank Zappa, as well as classical sources like Tchaikovsky and Messiaen, the band has been lumped in with the popular canon of post-punk or, more dreadfully, the “Post-Brexit” wave. In truth, since the band made their breakthrough with the instantly iconic Schlagenheim, black midi has been on the forefront of some of the most dynamic, cutting-edge virtuosity in rock music, leaning heavier into their jazz influences on last year’s thrilling Cavalcade without losing a shred of their unique, energetic touch. However, where Cavalcade saw the band stripping back a bit and touching smoother, more atmospheric notes with songs like “Marlene Dietrich” and “Diamond Stuff,” Hellfire finds the group once again dialing up their hypnotic energy, pairing dizzying instrumentals with apocalyptic imagery for a result that sounds at times like you’ve found yourself in the middle of a Faustian Looney Tunes segment.

Lead vocalist and guitarist Geordie Greep has been flirting with calamity since the band’s beginning, but never before Hellfire have his lyrics been quite so pointed towards devastation. His gift for injecting spellbinding narratives into his tracks—delivered with an inimitable voice that wavers between full-bodied shouts and devious purring—is reminiscent of Tolkien’s desire to create worlds simply for the sake of having a place for the many characters in his head to reside. On “Sugar/Tzu,” he portrays a crafty, egotistical boxer with devious intent, as speedy arpeggios, elevated by Morgan Simpson’s incomparable drumming and the blaring saxophone of frequent collaborator Kaidi Akinnibi, punctuate the terrible tale. Boxing arenas serve as a very logical setting for a black midi track: a room full of piss, vigor, aggression and diametrically opposed characters who force a visceral reaction from the listener. By the time the narrator violently executes his opponent in the ring, the deep frenzy of the instrumental has provided something close to a justification for the fighter’s actions—an impressive feat for a track that weighs in at under four minutes long.

Elsewhere on the album’s pernicious voyage, multi-instrumentalist and vocalist Cameron Picton guides the listener through the disastrous effects of man’s ill intent within a variety of settings. “Eat Men Eat” calls back to the evil mining company that made its debut in “Diamond Stuff,” zeroing in on a small troupe suffering under the rule of a malicious captain. Picton injects the story with his own staggering, terrible mental images, such as, “I love you, but I can feel my chest bubbling” and “Each day you wake and each night you sleep / I’ll be camped in your chest, burning, burning,” while also cleverly alluding to the characters’ sexuality and broader motivations.

“Eat Men Eat” is not only notable for its compelling narrative or the rapid, flamenco guitars that aid in crafting its atmosphere, but also for the strength of Picton’s vocal delivery. Earlier songs from the band that featured his lead vocals tended to sound a little more muted, which, while providing a charm of their own, created a tonal dissonance between himself and the more exuberant Greep. When he steps to the mic on Hellfire, it’s with a confidence that was absent in the past, as he dynamically elevates the tension on “Eat Men Eat” with his harsh yells and gritty delivery and, later in the tracklist, provides a satisfying apex to “Still” by belting out some high notes.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-