Bob Dylan’s 62 Greatest Songs of All Time, Ranked

This is our tribute to Judas—the best there is, the best there ever was, and the best there ever will be.

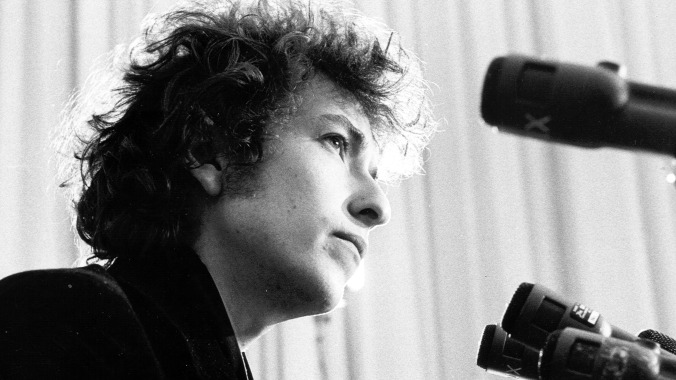

Photo by Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

There is, perhaps, no greater fool’s errand than trying to make any kind of ranking about Bob Dylan’s music. I know this as well as anyone, considering that a year ago this month I ranked all of Dylan’s albums from worst to best. But, with the recent release of A Complete Unknown, the most important songwriter of all time is in clear cultural focus. I figured, hey, why not try to make a stance on what his “greatest” work is? But, like I said, ranking Bob Dylan’s music is a task with no resolution. This list would look completely different tomorrow if I had to re-rank everything again.

So, in the spirit of Dylan himself, I have come up with a strange, contrarian amalgamation of studio songs, demos, outtakes and live performances and put them in an arbitrary order (except for #1 and #2). I am not really concerned with the typical cultural mapping of Dylan’s career. The only requirement for this list is that the songs all have to feature Dylan as either a co-writer or primary songwriter, so there are no entries from his Shadows in the Night, Fallen Angels and Triplicate era. I’ve also opted to forgo including any songs by the Traveling Wilburys. How did I land on 62 songs? Well, his first album came out in 1962 and I didn’t feel like writing 100 blurbs. Thanks for taking this ride with me, and let me know in the comments which entries you agree with and which you think need to be nuked immediately. Here are Bob Dylan’s greatest songs, ranked.

62. “Love Minus Zero/No Limit” (Bringing It All Back Home, 1965)

Pronounced like “Love Minus Zero over No Limit,” this is the unsung hero of Bringing It All Back Home, tucked into the middle of the album’s “electric side” in-between the lauded “Maggie’s Farm” and the oft-forgotten “Outlaw Blues.” It’s one of Dylan’s many great love songs, delivered with a melody that’s full of zen yet full of poetics that exist in a lineage shared with Edgar Allen Poe, the Book of Daniel and William Blake. Dylan does something profound on “Love Minus Zero/No Limit,” a song that certainly does not get enough flowers. “In ceremonies of the horsemen, even the pawn must hold a grudge / Statues made of matchsticks crumble into one another, my love winks, she does not bother, she knows too much to argue or to judge” is a tremendous, beautiful sequence.

61. “Went to See the Gypsy (Demo)” (Another Self Portrait (1969-1971): The Bootleg Series, Vol. 10, 2013)

The story goes that “Went to See the Gypsy” was written by Dylan after his meeting with Elvis Presley. The “He did it in Las Vegas, and he can do it here” lyric could be a reference to the King’s International Hotel residency! But Dylan told Douglas Brinkley that he’d never met Presley, nor did he want to. “I know the Beatles went to see him, and he just played with their heads.” “Went to See the Gypsy” appeared on side one of New Morning, but Dylan’s demo of the track is the version that I think about most—a demo featured on the Bootleg Series entry focusing on his Self Portrait era. It’s a stunning number, one with an acoustic guitar focus instead of the piano-and-bass arrangement that made the song’s final cut.

60. “Born in Time” (Tell Tale Signs: The Bootleg Series Vol. 8, 2008)

While “Born in Time” would wind up on Bob Dylan’s 27th album, Under the Red Sky, he wrote and began recording it while working on his 26th album, Oh Mercy. There are quite a few outtakes and demos from the Oh Mercy sessions, all of which appear on the Tell Tale Signs entry of the Bootleg Series, that are far superior than their final tracklist renditions, and “Born in Time” is one of the greatest instances of that. The outtake performance is dreamy and romantic, and one of his best post-Infidels recordings. The Under the Red Sky re-working is not bad, but Dylan had lost the magic of the Oh Mercy sessions in the transition.

59. “Fourth Time Around” (Blonde on Blonde, 1966)

“Fourth Time Around” was one of the first Dylan songs I ever loved, or at least that’s how I remember it. It’s one of the defining attributes of Blonde on Blonde, albeit one that is overshadowed by the usual suspects, like “I Want You,” “Visions of Johanna” and “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35.” But “Fourth Time Around” begins beautifully and never relents, morphing into this uber-pleasant pocket of plucky, baroque-folk splendor. Dylan “going electric” feels absent here, in the chamber-pop craft of harmonica pulls and dense, star-making acoustics. Is “Fourth Time Around” the best song about chewing gum ever made? Perhaps. If not, it being one of the best songs on Blonde on Blonde can be its consolation prize.

58. “Tomorrow Is a Long Time” (Greatest Hits, Vol. 2, 1971)

Though it was recorded before The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan was completed, “Tomorrow Is a Long Time” only exists on The Bootleg Series Vol. 9 and Greatest Hits Vol. 2. The version we all know and love is from a concert on April 12, 1963, at Town Hall in Midtown Manhattan. Because of its inclusion in Dylan’s second greatest hits entry, “Tomorrow Is a Long Time” doesn’t have the mysticality of his other bootleg tracks. However, it remains one of his prettiest works. It’s familiar to other love songs Dylan wrote around the same time, including “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right” and “Girl from the North Country,” but it’s the first real, recorded instance of his ability to master the romantic quadrants of the American Songbook in novel ways: “Yes and only if my own true love was waitin’ / And if I could hear her heart a-softly poundin’ / Yes, only if she was lyin’ by me / Then I’d lie in my bed once again.”

57. “When the Ship Comes In” (The Times They Are A-Changin’, 1964)

Bob Dylan’s run of folk records, from his self-titled through Another Side, can sometimes blend together for me, but there is no doubting that “When the Ship Comes In” is one of his most melodic efforts of that era. I hate to say this, but “When the Ship Comes In” is arguably one of the most danceable folk songs ever written, as there’s a shake and a rattle in Dylan’s guitar that, while not intentionally poppy, has an undeniable groove to it. Though there is a songwriting nod to Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill’s “Pirate Jenny,” Joan Baez said that Dylan was inspired to write the song when a hotel clerk wouldn’t give him a room because he looked “unwashed.” What “When the Ship Comes In” became, however, was this massive, epic allegory about outmuscling oppression, fit with references to the Pharaoh’s drowning, the Red Sea and Goliath’s defeat. All of that because Bob Dylan was stinky… that’s rock ‘n’ roll history right there.

56. “Don’t Fall Apart On Me Tonight (Version 2)” (Springtime in New York: The Bootleg Series, Vol. 16 / 1980-1985, 2021)

As he made the transition back to secular music after his born-again trilogy concluded, Dylan found a muse in love and loss once again when he decamped to the Power Station to make Infidels. It’s the best thing he made in the 1980s, so it shouldn’t be shocking that the Bootleg Series focused on it is a damn goldmine. I think the second version of “Don’t Fall Apart On Me Tonight” is one of the best bootleg tracks in Dylan’s entire catalog, a recording that somehow magnifies the source material into even greater brilliance. The track, and all of Infidels, features one of Dylan’s greatest backing bands—Mark Knopfler, Robbie Shakespeare, Mick Taylor, Benmont Tench, Sly Dunbar and Alan Clark—and it’s a great gesture of jangling Heartland rock. “Don’t Fall Apart On Me Tonight” is, to me, a great example of one of the best Dylan eras—a perfect marriage of his protest singer origins and the jazz-infatuated crooner he’s become since 1997.

55. “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues” (Highway 61 Revisited, 1965)

Overshadowed by the song that follows it (“Desolation Row”), “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues” is a cracked-out gem on Highway 61 Revisited’s second side. Now, did Bob Dylan ever go to Juarez on Easter and witness a world of corruption, drinking and drugging, whores and saints? I’d say probably not, but there is an astonishing amount of mysticism on “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues,” so much scene-setting that it turns into a haunted, on-the-road-style “evocation of muddied consciousness,” as author Paul Williams once put it. “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues” features a bunch of verses and no choruses. It’s just Dylan throwing haymaker after haymaker. “I’m going back to New York City, I do believe I’ve had enough,” he says, before puffing his harmonica into dislocated oblivion.

54. “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere (Studio Outtake)” (Greatest Hits, Vol. 2, 1971)

Recorded in upstate New York with The Band, “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere” is one of Bob Dylan’s best country tracks—a proper and spiritual cousin to Nashville Skyline but with a looser, raggedy mysticism wrapped around it. I love how picturesque it is, as Dylan yearns for a “tree with roots,” “a gun that shoots,” kings “supplied with sleep” and a bride that’ll arrive tomorrow. The Byrds made the song their own in 1967, while Joan Baez, Loudon Wainwright III and Old Crow Medicine Show all have great versions of it, too. When I think about folk songs as timeless as what Guthrie and Seeger were writing, “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere” is in those conversations, too.

53. “The Groom’s Still Waiting At the Altar” (Shot of Love, 1981)

Written during the summer of 1980, “The Groom’s Still Waiting At the Altar” is the kind of song that, lyrically, belongs firmly in the context of Shot of Love. But sonically, it’s music that rivals the ferocity of Highway 61 Revisited. While Dylan’s born again trilogy left a lot to be desired by his fans, even when his surrealistic religious imagery splashed, “The Groom’s Still Waiting At the Altar” is a good example of one universal truth: Even at his “worst,” Bob Dylan is still much better than almost everyone else. We’re talking about one-four-five blues performed like a sharp-toothed gospel. From a language perspective, this is Bob at an apex. “Cities on fire, phones out of order, they’re killing nuns and soldiers, there’s fighting on the border” and “Prayed in the ghetto with my face in the cement, heard the last moan of a boxer, seen the massacre of the innocent” are some of his most arresting, page-turning lines post-Blood on the Tracks.

52. “My Back Pages” (Another Side of Bob Dylan, 1964)

To me, “My Back Pages” and “Mr. Tambourine Man” co-exist as a two-part anthem of past-self abandonment. “My Back Pages” is Dylan letting go of his “spokesman of a generation” title and writing for himself. It sounds like a protest song, and maybe it is in a less universal sense, as you can imagine Dylan on an empty stage, standing up straight and putting his proverb through the wires of a microphone. But there is a dismissal of old truths here. “Yes, my guard stood hard when abstract threats too noble to neglect deceived me into thinking I had something to protect,” he sings, burning the very template he made. Few choruses feel as painfully familiar as this one: “I was so much older then, I’m younger than that now.”

51. “I Shall Be Released (Live at Nippon Budokan Hall, Tokyo)” (The Complete Budokan 1978 (Live), 2023)

The Budokan 1978 recordings have been circulating around for years, thanks to the Bob Dylan at Budokan disc released that year. But The Complete Budokan package that came out in 2023 offered an expansive look into one of Dylan’s most polarizing concert performances—thanks to dense, full-band arrangements and stylings that would come to define his sound for the next decade. Look to The Complete Budokan and you’ll see a man certainly priming himself for the Slow Train Coming and Saved years to come. It’s hard to pick a definitive performance of “I Shall Be Released,” especially because the Band perfected it on Music from Big Pink in 1968, but I do believe that the way Dylan played it at Budokan rivals it better than most anything else.

50. “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)” (Rough and Rowdy Ways, 2020)

I watched Dylan perform this song live in 2021 on a very, very cold Columbus night, and it has stuck with me ever since. He played other songs I loved, too, like “Melancholy Mood,” “To Be Alone With You” and “Every Grain of Sand,” but his singing of “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)” brought the house down just halfway into his set. As the concluding track to Rough and Rowdy Ways‘s first side, it’s an improbable measure of the Dylan we became reacquainted with nearly five years ago. The multiplicity of the self, ever the perfect Bob Dylan concept, remains a fascinating one here—as he waxes poetic about an outlaw surfing radio stations while driving down U.S. Route 1. An accordion thrums along, while Dylan recounts the sights: Mallory Square, where Truman’s White House was, the land of Oz and the Fishtail Palms. Rituals bloom with summer and it’s hot down there, in the “tiny blossoms of a toxic plant.” “Key West is the place to be, if you’re looking for your mortality,” Dylan sings. “Key West is paradise divine.” To me, the Key West he is imagining is one that looks a lot like the music business, summed up in the song’s final moments: “If you lost your mind, you’ll find it there.”

49. “I Threw It All Away” (Nashville Skyline, 1969)

On the perfect Nashville Skyline, Dylan plucks his way through the remorseful reckoning of “I Threw It All Away,” a lost-love song backed by Kenneth A. Buttrey’s snare drum and Bob Wilson’s weeping, Highway 61-summoning organ. The track contrasts with Dylan’s previous failed-romance laments, like “One of Us Must Know (Sooner or Later)” and “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right,” with him adopting accountability for his failures, and its endearing, peace-be-with-you thesis is the centerpiece of Nashville Skyline’s affections: “Love is all there is, it makes the world go ‘round.”

48. “Not Dark Yet” (Time Out of Mind, 1997)

Put all of the Time Out of Mind songs on a door, throw a dart at them, and whatever you land on is probably one of Bob Dylan’s best songs. While its reverence was heightened by the “comeback” label quickly affixed to its release, Time Out of Mind is one of Bob’s greatest works no matter what anyone else is saying about it. He won an Album of the Year Grammy for it, casting his immortality in solid gold after, let’s be honest, almost 20 years of mostly piss-poor contributions to his post-Blood on the Tracks legacy. I think there are a few perfect songs on Time Out of Mind, but it’s hard to argue with the dynamic, splendid work of “Not Dark Yet.” A softball pick, especially in the company of “Love Sick,” “Highlands,” “Make You Feel My Love” and “Cold Irons Bound”? Sure, but it’s a song that’s lived a thousand lives on its own—marking the true renaissance of America’s greatest wordsmith.

47. “Jokerman (Live on Late Night With David Letterman)” (1984)

Infidels is the best album Bob Dylan released between 1977 and 1996, and that is thanks to the very good “Jokerman”—a syrupy, waltzing, Mark Knopfler and Mick Taylor-touched guitar tune that flirts with smooth jazz but is unequivocally what debris was left after his born-again trilogy concluded by 1983. I’ve never heard a bad version of this song, but one of Dylan’s all-time greatest moments came when he performed a noticeably punkier, unbridled rendition of the track on Letterman a year later. “The book of Leviticus and Deuteronomy, the law of the jungle and the sea are your only teachers” sounds like a much angrier proverb when Dylan funnels a swinging menace into it.

46. “Soon After Midnight” (Tempest, 2012)

When I think of Tempest, I think of the 14-minute, 45-verse title track about the Titanic. But, when I move backwards through the record, I am met by “Pay in Blood,” “Duquesne Whistle” and “Early Roman Kings.” I think “Soon After Midnight” is one of Dylan’s best jazz-era songs, rivaling anything on Modern Times, quite frankly. His gravelly vocals sound like a balm here, thanks to the arrangement of Donnie Herron’s pedal steel and the three-part guitar work from David Hidalgo, Stu Kimball and Charlie Sexton sitting beneath it. The Shakespeare-referencing “Soon After Midnight” is a gentle waltz done in A major, and it’s one of the best murder ballads ever written. With lyrical context, the “It’s soon after midnight, and I don’t want nobody but you” lines become far more sinister than their surface-level tenderness might initially suggest.

45. “Wedding Song” (Planet Waves, 1974)

It’s a song that Bob Dylan has rarely performed, and it’s greatly overshadowed by the two-part “Forever Young,” but “Wedding Song” is the best part of Planet Waves. Its meaning only gets heavier over time, too. “I love you more than ever and I haven’t yet begun” is just one of the great phrases Dylan works with here, as “Wedding Song” is a bounty of affirmations washed with a fear of loss. In marriage, in Dylan’s eyes, there are two souls worth saving and, in marriage, there is a love that “doesn’t bend” when faced with a crumbling world. To adore is to grieve, as devotion and tragedy are like siblings, even when you love someone more than you love yourself. I do not return to Planet Waves often enough, but when I do, I am reluctant to let the record slip into “Wedding Song”—it makes me weep far too often.

44. “Isis (Live at Boston Music Hall, November 1975)” (The Bootleg Series, Vol. 5: Live 1975 – The Rolling Thunder Revue, 2002)

Because he wrote “Isis” with Jacques Levy, Bob Dylan made Desire—so we can be thankful for its existence in that sense. But there is a spark of menace in Dylan’s voice on a track like this one, which was written and recorded at the same time his marriage to Sara was collapsing and re-building. But it’s a myth-driven, Odyssey-paralleling song, too. “What drives me to you is what drives me insane,” Dylan scorns. “I can still remember the way that you smiled on the fifth day of May in the drizzlin’ rain.” I think the Desire version of the song is great, but Dylan and The Band’s performance of it from November 1975 on the Rolling Thunder Revue Tour ought to go down as one of the greatest live songs ever captured—as Dylan stood at the microphone with his face painted white and blew flames into his harmonica without, for the first time, a guitar hanging off his shoulder.

43. “Sara” (Desire, 1976)

A spiritual sequel to “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands,” “Sara” is the crown jewel of Desire and one of Dylan’s all-time best love songs. It’s an autobiographical, referential waltz written like a eulogy but delivered like pillow talk. Dylan and his longtime wife Sara were on the brink of divorce, yet “Sara” is a token of great, mystified affection. To be called a “scorpio sphinx in a calico dress,” a “radiant jewel” and “glamorous nymph with an arrow and bow” is to not only be known but to be remembered. It is said that the first take Dylan and his band played is the one that made Desire’s final cut, and Scarlet Rivera’s violin paints an ever-sore-hearted picture of a once-fruitful marriage existing in memory only. “Sara” is a deliverance of preciousness and a reckoning of human love without an expiration date.

42. “She’s Your Lover Now (Studio Outtake)” (The Bootleg Series, Vols. 1-3 (Rare & Unreleased) 1961-1991, 1991)

Originally recorded for inclusion on Blonde on Blonde, “She’s Your Lover Now” didn’t see a release until The Bootleg Series Vols. 1-3 in 1991. Its chord progression is similar to “Like a Rolling Stone,” but Dylan’s vocal performance is done in the style of “Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blue Again.” The song took 12 hours to record, with 21 takes to choose from when it was all said and done. Unfortunately, Dylan hated all of them and cut the track off the album. But undeniably, “She’s Your Lover Now” is one of Dylan’s sharpest lyrical performances; the track is poetic in the esoteric way that most of Blonde on Blonde is. “She’ll be standin’ on the bar soon / With a fish head an’ a harpoon / An’ a fake beard plastered on her brow / You’d better do somethin’ quick / She’s your lover now,” he sings. The track is chaotic and cluttered, but in a linguistically harmonious way that only Dylan can pull off. Through mermaid imagery, castles and lost memories, “She’s Your Lover Now” is the closest thing we have to a Bob Dylan fairytale. Yet even that label feels unfit. The song gnaws away at you, as there’s something angry about its sound, even through all of its mysticality.

41. “Positively 4th Street” (Greatest Hits, 1967)

Asshole Bob Dylan is my favorite, and “Positively 4th Street” is the contemptous rave every songwriter worth their salt dreams of penning. The song is poisoned with jealousy not to a fault, but to a triumph. My friends and I used to listen to “Positively 4th Street” during free periods in the computer lab, blaring it in our video production class’ recording room near a hushed library. “I wish that, for just one time, you could stand inside my shoes,” Dylan’s voice rang out everywhere. “You’d know what a drag it is to see you.” “Positively 4th Street” got the single treatment right after “Like a Rolling Stone” in 1965, but it never landed on a studio album until Dylan’s Greatest Hits came out two years later.

40. “Brownsville Girl” (Knocked Out Loaded, 1986)

Knocked Out Loaded is one of Bob Dylan’s worst albums, but “Brownsville Girl” is, easily, one of his greatest efforts—especially in the 1980s. Co-written with Sam Shepard, it was brought into the studio (titled as “New Danville Girl”) while Dylan and his band were making Empire Burlesque in late 1984. It wasn’t until 1986 that he dusted off the outtake and re-worked it into something magical. Dylan paid tribute to the late Woody Guthrie with the song, as the folk hero had written something called “Danville Girl,” but the homage is much stronger on “New Danville Girl” than “Brownsville Girl.” I like the Springtime in New York rendition of the song, which went unreleased until 2021, but arguing with the gospel-evoking, blues-and-country magnitude of the Knocked Out Loaded cut would be one of the greatest fool’s errands. “I think that is one of the greatest things I ever heard in my life,” Lou Reed said in 1987. True to Reed’s words, “Brownsville Girl” is this epic, funny and implausibly tremendous opera of mystique that features a humungous horn section and Dylan waxing poetic on the plot of the Gregory Peck-starring film The Gunfighter.

39. “When I Paint My Masterpiece (Demo)” (Another Self Portrait (1969-1971): The Bootleg Series, Vol. 10, 2013)

“When I Paint My Masterpiece” is, infamously, one of Dylan’s songs made most famous by the Band, who recorded it for their 1971 album Cahoots. It was also heavily featured in Grateful Dead sets in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s. But Dylan’s attempts at recording the song have always won out, at least for me. He first worked on it at Blue Rock Studio with Leon Russell and Jesse Ed Davis, and he wound up making it around the same time as “Watching the River Flow.” Both tunes would find a home on his second greatest hits compilation, but the definitive performance of “When I Paint My Masterpiece” is the piano demo released on Another Self Portrait in 2013. The lyrics are slightly altered, but the song’s wisdom glows in the company of Dylan’s cracking croon.

38. “Tangled Up in Blue” (Blood on the Tracks, 1975)

The go-to Blood in the Tracks song is usually “Tangled Up in Blue.” It’s not my favorite from the record, but there’s no doubting what its legacy represents in the context of Dylan’s career. It’s the opening song from his, arguably, greatest existing work, and it’s as genius as it is shadowed by an immeasurably profound darkness. “All the people we used to know, they’re an illusion to me now,” Dylan sings. “Some are mathmeticians, some are carpenters’ wives—don’t know how it all got started, I don’t know what they’re doin’ with their lives, but me, I’m still on the road.” With allusions of Dante and Petrarch just out of focus, Dylan crafts an unreliable narrative out of “Tangled Up in Blue” with vague, collaged images that arrive abstract yet profound. Within the vignettes, however, is a mark of aching distance—a longing defined by Dylan singing “We just saw it from a different point of view.” “Tangled Up in Blue” is messy but observational, a powerful thumb pressed into Blood in the Tracks’s throbbing pulse.

37. “Ballad of a Thin Man” (The Real Royal Albert Hall 1966 Concert, 2016)

Historically, this is the song that comes right before someone calls Bob Dylan “Judas” in 1966. He was playing at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester, delivering a seven-and-a-half-minute sermon on an absolute dud of a human being named “Mister. Jones.” “Ballad of a Thin Man” is Bob Dylan at his most vengeful, dropping bar after bar of scorched-earth, fuck-you parables. Mister Jones simply doesn’t get “it”—the “it” being something “happening here”—but he’s handsome, lawyered up and he’s “been through all of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s books.” The circus laughs in his face; a sword-swallower says “here is your throat back, thanks for the loan” and a one-eyed midget calls him a cow. Mister Jones “should be made to wear earphones,” Dylan ridicules, as he fingers his piano and the band drapes him in shadowy, organ-glowed textures of doom.

36. “Oh, Sister” (Desire, 1976)

As soon as “Oh, Sister” begins, the unmistakable singing of Emmylou Harris sticks out. Her vocals pair well with Dylan’s, and her voice is, in part, what makes Desire one of his greatest works. The song became a live staple (and favorite) on the Rolling Thunder Revue tour just before Desire came out, and I believe it’s one of Dylan’s most hopeful performances. Here, “time is an ocean” and we may not see our loved ones again. But an apocalypse can be a dance, and our purpose can be one of affection by way of God and ourselves. “We grew up together, from the cradle to the grave,” Dylan sings. “We died and were reborn and then mysteriously saved.” Scarlet Rivera’s violin weeps in tandem with Dylan’s harmonica, while Howard Wyeth’s drums thud into us. “Oh, Sister” is a picture-perfect capsule of some of his strongest musicality.

35. “When the Night Comes Falling from the Sky” (The Bootleg Series, Vols. 1-3 (Rare & Unreleased) 1961-1991, 1991)

“When the Night Comes Falling from the Sky” first appeared on Empire Burlesque in 1985, but the outtake featured on the (Rare & Unreleased) edition of the Bootleg Series in 1991 remains one of Dylan’s greatest what-could-have-beens. Featuring E Street Band members Steven Van Zandt and Roy “The Professor” Bittan, the song comes to life with this pastiche of blue-collar rock sonics straight from a Springsteen session. Dylan sounds renewed here, singing with a glob of bite and quickness that measures up to Van Zandt’s guitar playing. The Professor’s keyboards sound like jumper-cables here, too, making “When the Night Comes Falling from the Sky” one of Bob Dylan’s most urgent pieces.

34. “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” (Bringing It All Back Home, 1965)

Howard Sounes called “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” Bob Dylan’s “grim masterpiece,” and I would have to agree with that assessment. The song is existential to a maddening fault, marking Dylan’s pivot away from the on-the-nose political dirges he’d been sketching for three years prior. When he gave Bringing It All Back Home to the world in 1965, he elected to make the epic, dense “It’s Alright, Ma” the album’s penultimate track—a startling, seven-minute nose-dive on the lauded “acoustic side” of the record. There are far too many lyrics to point out here—the “he not busy being born is busy dying” line is wisely beloved—but I’ve always been fond of “Disillusioned words like bullets bark, as human gods aim for their mark, make everything from toy guns that spark to flesh-colored Christs that glow in the dark” and the verse’s conclusion of “It’s easy to see without looking too far that not much is really sacred.” As far as “menacing” songs in Dylan’s career go, it doesn’t get much bleaker than “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding).”

33. “Blind Willie McTell (Studio Outtake)” (The Bootleg Series, Vols. 1-3 (Rare & Unreleased) 1961-1991, 1991)

Recorded in 1983 and released on The Bootleg Series Vols. 1-3, “Blind Willie McTell” is one of the tracks that failed to make it onto the final cut of Infidels. Dylan had based the song’s melody off of “St. James Infirmary Blues,” a jazz standard made popular by Louis Armstrong, and told the story of Blind Willie McTell, a Georgian Piedmont blues pioneer who revolutionized fingerpicking and the use of a 12-string guitar. It’s an allegorical reflection on the intersection of slavery and American blues, something Dylan would explore on “High Water (For Charley Patton)” on Love and Theft and “Goodbye Jimmy Reed” on Rough and Rowdy Ways. With Dire Straits frontman Mark Knopfler on guitar and Dylan on piano, “Blind Willie McTell” properly emphasizes the songwriter’s comeback after a string of three evangelical records. It was a return to impassioned lyricism, using Southern imagery and Bible scripture to tell the century-spanning history of oppression in America. Dylan disciples consider “Blind Willie McTell” as one of his best compositions, and for good reason.

32. “Up to Me” (Biograph, 1985)

The mystery of why “Up to Me” was left off of Blood on the Tracks remains unsolved. Though the album is widely considered a masterpiece, “Up to Me” might have skewed that designation, given how it contradicts the passive ethos sprinkled across the tracklist we all know and love. The song would later find a home on the Biograph box set in 1985, and later on Side Tracks and The Bootleg Series, Vol. 14. “Up to Me” is a beautiful track echoing the melancholia of the album it was scrapped from. However, on the other songs on the record, Bob Dylan’s character found himself in the throes of a heartbreak he couldn’t avoid. On “Up to Me,” his character is tasked with circumventing his despair; to be or not be alone is his choice. “Well I watched you slowly disappear down into the officers’ club / I would’ve followed you in the door, but I didn’t have a ticket stub / So I waited all night ‘til the break of day, hopin’ one of us could get free / When the dawn came over the bridge, I knew it was up to me,” Dylan sings. There are 12 verses, each sharing the same refrain. In the context of his catalog, “Up to Me” is that one track that benefits more from being albumless. It sounds too much like a Blood on the Tracks song to have wound up on Desire, yet it doesn’t align with the storytelling perspective of the former. It’s the only Dylan song that belongs in the purgatory of bootlegs. “Up to Me” does not need a forever home; it transcends the confines of one article of time.

31. “Forever Young (Concert Version) [ft. The Band]” (The Last Waltz, 1978)

I didn’t want to choose between the two recordings of “Forever Young” from Planet Waves, so, instead, I chose the greatest performance of it that exists: Dylan singing it with The Band on the Winterland Ballroom stage in 1976. It’s a powerful rendition and a Thanksgiving tradition as good as any. Garth Hudson and Richard Manuel do an organ-piano waltz while Robbie Robertson’s guitar breathes fire and Rick Danko and Levon Helm put a once-in-a-lifetime shine on their backing vocals. I hear this recording and I weep. Dylan had never sounded better than this and neither had The Band. That we got this performance on film remains one of humanity’s sweetest and most-plentiful fruits.

30. “One of Us Must Know (Sooner or Later)” (Blonde on Blonde, 1966)

Closing out one of the greatest side ones in rock ‘n’ roll history, “One of Us Must Know (Sooner or Later)” is the unsung giant of Blonde on Blonde largely overshadowed by tracks surrounding it—especially “I Want You,” “Visions of Johanna” and “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35.” If “Positively 4th Street” is the triumphant, brazen apex of Bob Dylan’s linguistic brutality, then “One of Us Must Know” is the heavenly aftershock full of just as much ache and disdain. “I told you as you clawed out my eyes that I never really meant to do you any harm,” Dylan sings while Al Kooper’s organ sprawls through a piano run from Paul Griffin’s fingertips. The Band’s Robbie Robertson and Rick Danko make an appearance alongside some vets from the Bringing It All Back Home sessions, folding into an ensemble that built “One of Us Must Know” into something brilliant after playing 24 takes in nine hours at Columbia A.

29. “Most of the Time” (Oh Mercy, 1989)

A song so good it makes Oh Mercy one of Dylan’s greatest albums, “Most of the Time” has lived a lot of lives in its near-36-year existence. Dylan imagined it as, initially, a stripped-bare folk song, but Daniel Lanois wanted it to sound more akin to the atmospheric, dreamy style that would consume most of Knocked Out Loaded, Oh Mercy and Under the Red Sky. That acoustic idea wound up on the Tell Tale Signs disc, but I really do prefer Lanois’s production than Dylan’s minimalist efforts. “I can smile in the face of mankind, don’t even remember what her lips felt like on mine most of the time” is among my favorite Dylan lyrics, and the string quartet of four Les Paul parts, paired with Lanois’s bass playing, makes for a sweeping blanket of blissful, quixotic rock music.

28. “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll (Live at Boston Music Hall, November 1975)” (The Bootleg Series, Vol. 5: Live 1975 – The Rolling Thunder Revue, 2002)

When he picked up his pen in mid-1963 and wrote about the death of a 51-year-old Black barmaid named Hattie Carroll at the hands of a wealthy white man in Charles County, Maryland, Dylan had already found his niche in telling stories. And “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” isn’t so much a protest song as it is a recounting of events—much like “Hurricane” would be more than a decade later. Considered the voice of a generation, many saw Dylan’s words as a mark of resistance. And, whether or not he was interested in being a mouthpiece for anything, him just saying the words, that William Zantzinger killed Carroll, was a radical act; him singing “Oh, but you who philosophize, disgrace and criticize all fears, bury the rag deep in your face for now’s the time for your tears” was a radical act. Perhaps his intentions were not long-term, yet his efforts were immense and without expiration. As he said himself, “[‘The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll’] wasn’t a protest song or a topical song and there was no love for people in it.” Zanzinger was convicted of manslaughter on the same day Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech at the March on Washington, an event Dylan and Joan Baez sang at together. He hocked the original melody from a traditional folk song called “Mary Hamilton,” but the live performances of the song later on gave it a much more dynamic sound. And, as is the case with numerous Bob Dylan songs, his performance of it with the Band on the Rolling Thunder Revue tour is superior and breathes new life into a key part of folk music’s canon.

27. “I’ll Keep It With Mine (Take 1, Piano Demo)” (The Cutting Edge 1965-1966: The Bootleg Series, Vol. 12, 2015)

There are a few versions of this song lingering around, but the one featured on both Biograph and The Cutting Edge is, to me, among Dylan’s greatest ballads. He’d recorded a demo in 1964, but this version got cut during the Bringing It All Back Home sessions in January 1965. It was once called “Bank Account Blues,” but now it’s called “I’ll Keep It With Mine” and it’s rough but beautiful. The second verse is one of Dylan’s finest: “I can’t help it if you might think I am odd. If I say I’m not loving you for what you are but for what you’re not, everybody will help you discover what you set out to find.”

26. “Boots of Spanish Leather” (The Times They Are A-Changin’, 1964)

No poet has ever understood the restlessness of love better than Bob Dylan. The epistolary wonder of “Boots of Spanish Leather” corroborates such a truth, as Dylan reckons with a hope entrenched in distance. His then-girlfriend Suze Rotolo was away in Italy, and “Boots of Spanish Leather” puts their relationship into a capsule of vulnerability. It’s a forlorn tale standing on the shoulders of two lovers at a crossroads. The titular boots arrive as a gift of affection, only to become a gift of goodbye by the song’s end—one of Dylan’s most gut-wrenching and evolving symbols ever sculpted into lyrics. “Boots of Spanish Leather” is not just the best song on The Times They Are A-Changin’, but maybe the most important love ballad of its time.

25. “When the Deal Goes Down” (Modern Times, 2006)

In 2004, Dylan told Newsweek that he was working on a song based on the melody of “Where the Blue of the Night (Meets the Gold of the Day),” and what came of it was “When the Deal Goes Down,” the likely Robert Johnson-inspired pinnacle of Modern Times. A proper end-cap to Dylan’s Y2K renaissance, “When the Deal Goes Down” chronicles a melting pot of blues, soul and singer-songwriter and charts this immaculate session of great players—Denny Freeman, Tony Garnier, Donnie Herron, Stu Kimball and George Receli—turning Dylan’s adaptations into cherry wine. “When the Deal Goes Down” is timeless and a proper example of the “transient joys” surrounding Modern Times altogether.

24. “Visions of Johanna” (Blonde on Blonde, 1966)

Known originally as “Freeze Out,” “Visions of Johanna” is often the consensus #1 draft pick from Blonde on Blonde, and I don’t begrudge those who make that choice—it’s very likely the song that bridges the gap of impressionism that exists between Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde. “Visions of Johanna” is written about two women, the ever-lingering Louise and our titular mystic, but remains a meditation on perfectionism, with a focus on a city honeymoon that’s brief and strange. It’s an elegy, an ode and a triumph all at once, wrapped in subtleties and full of delicate (“The ghost of ‘lectricity howls in the bones of her face”) and humorous (“Mona Lisa musta had the highway blues, you can tell by the way she smiles”) language. Much like the rest of Blonde on Blonde, “Visions of Johanna” is an epic tale of hopelessness summarized by one of the sharpest uses of “and all” in rock history.

23. “Sign on the Window” (New Morning, 1970)

I struggle to find many entries in rock’s pantheon as sublimely domestic and handsome as “Sign on the Window,” the greatest part of New Morning and my personal pick for Bob Dylan’s best song of the 1970s. I first heard “Sign on the Window” when I was still a novice Dylan fan, when it played at the end of the season eight finale of Friends. I was gobsmacked by its beauty, so taken aback by the “build me a cabin in Utah” verse that, some 10 years later, I wrote an entire poetry book based off of it. Dylan’s ability to rhyme “California” with “warn ya” is remarkable, as is his ability to lend such a gentleness to a couplet like “sure gonna be wet tonight on Main Street, hope that it don’t sleet.” The quiet-living era of Dylan’s career is unremarkable to some but necessary to most, and “Sign on the Window” is its come-one-come-all exhale. As the man himself says, that must be what it’s all about.

22. “Like a Rolling Stone” (Highway 61 Revisited, 1965)

Every time Al Kooper’s organ kicks in at the dawn of “Like a Rolling Stone,” you can hear exactly how it, at once, healed the musical world and burned down all of its pillars. It’s a treasure to still have this song forever, as it christened a new age of rock ‘n’ roll into existence. Here, the protest singer from Greenwich Village becomes a translator of the world at large, siphoning all of his best and most absurd poetics into this vacuum of raucous, blues-based energy. A million words or more have already been written about “Like a Rolling Stone,” but few songs in the English language have ever been as consequential—and someone new is discovering it every day. How incredible is that?

21. “Caribbean Wind” (Biograph, 1985)

An outtake from the Shot of Love sessions thrown onto the third disc of Biograph, it amazes me that Dylan left this off the final cut of the album. My argument is, had he actually left it on the tracklist, we’d be talking about Shot of Love being one of his all-time best albums—somewhere around the Love and Theft or Infidels. I mean, “Caribbean Wind” is as perfect a song as you can get—and it was mysteriously left off of the Trouble No More chapter of the Bootleg Series (there is, however, a rehearsal version included on the deluxe-edition). I look at Bob Dylan’s discography between 1979 and 1989 and see a lot of cracks, but “Caribbean Wind” is no such failure. There are a few other versions of the song out there, but this is, to me, the definitive one. The audio of women inhaling deeply is a fun touch.

20. “Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts” (Blood on the Tracks, 1975)

Let’s pour one out for Lily, Rosemary and that no-good Jack of Hearts. While it’s not the song from Blood on the Tracks, it’s easily one of the best of Dylan’s “epic” tracks—clocking in at a whopping nine minutes and defining the already-stacked side two of the album. It’s nestled in-between “Meet Me in the Morning” and “If You See Her, Say Hello,” and “Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts” is this smorgasbord of characters, including Big Jim, the Hanging Judge and the titular trio. An entanglement of romance and crime, Dylan turns love into, as writers Philippe Margotin and Jean-Michel Guesdon aptly put it, a comedy and life into “a game of chance.” It’s the outlier song on Blood on the Tracks, and it likely should have been substituted for the more thematically-adjacent “Up to Me,” but nevertheless, it’s one of the greatest stories ever told via song. Facades and consequences linger here just as they do in much of Bob Dylan’s best work, and “Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts” looks to justice in the wake of mercy.

19. “Mississippi” (Love and Theft, 2001)

A lot of the attention gets put on Time Out of Mind, because it’s one of the greatest comeback records ever made. But, I’d argue that Love and Theft being as good as it is almost a more impressive feat. Only Bob Dylan could follow up a masterpiece with another one; he’d done it twice before, in 1965/66 and in 1975/76. The crown jewel of Love and Theft is “Mississippi,” one of those songs that, in the context of Dylan getting likened to Shakespeare and Twain, is rich with a waltzing truth. Sheryl Crow said it best: “[Bob Dylan] never gets older to me. That’s what mythological characters are all about.” I don’t know if he’s the first person to ever say “Well, the emptiness is endless, cold as the clay / You can always come back, but you can’t come back all the way” in our long, always-changing humanity, but every syllable feels new rolling off of Dylan’s tongue.

18. “Tonight I’ll Be Staying Here With You (Live at Montreal Forum, December 1975)” (The Bootleg Series, Vol. 5: Live 1975 – The Rolling Thunder Revue, 2002)

“Tonight I’ll Be Staying Here with You” was written by Dylan at the Ramada Inn he was staying at in town during the making of Nashville Skyline, and you can hear the way it shares a cord with a John Wesley Harding cut like “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight.” It’s a tune about devotion, one not so shattered by the unsettled, imperfect love that so often plagued Dylan’s earliest love songs—like “Love Minus Zero/No Limit,” “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands” and “Boots of Spanish Leather.” It’s homely yet glacial, rolling in on the tail of a piano run and full of train imagery and subtle, implicating marks of sorcery: “Is it really any wonder,” Dylan sings, “the love that a stranger might receive? You cast your spell and I went under, I find it so difficult to leave.” The lyrics aren’t as baroque as the cinematic, herculean efforts on “Visions of Johanna” or “Mr. Tambourine Man,” but they gnaw at the universal truths of vacancy that Dylan has so impressively regaled in much of his work. While the Nashville Skyline recording is timeless, so is Dylan and The Band’s performance of the track at the Montreal Forum in late 1975—a life-altering four minutes miraculously caught on tape.

17. “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” (The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, 1963)

In popular culture, “Blowin’ in the Wind” is Dylan’s juggernaut protest anthem—a song so recognizable that even the most staunch “I’ve never heard a Bob Dylan song” practitioners can’t argue against knowing it. But, to me, the crown jewel of Dylan’s political songs is “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall,” the closing number on side one of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. It’s a symbolistic masterpiece, as Dylan takes aim at pollution and nuclear warfare in the wake of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Reading microfiche newspapers at the library, Dylan became “aware of nothing but a culture of feeling, of black days, of schism, evil for evil, the common destiny of the human being getting thrown off course.” In turn, he penned this “funeral song” that’s idiosyncratic yet resounding. The best way to remember it is in this way: Dylan, subtly, laughs as he sings “And who did you meet, my darling young one?” Without taking a beat, he follows: “I met a young child beside a dead pony.” May we weep at the feet of “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” in perpetuity.

16. “Every Grain of Sand” (Shot of Love, 1981)

“I felt like I was just putting words down that were coming from somewhere else,” Dylan once said of “Every Grain of Sand.” I’m inclined to believe him, as “Every Grain of Sand” is the biblically-minded effort of his that feels most touched by some higher power. “Sometimes I turn, there’s someone there, other times it’s only me” is one of his most powerful lines, and a glimmer of righteousness that is not selfish but clear-minded. Shot of Love gave Dylan’s audience a tremendous finale to his born-again trilogy—a radically well-intentioned conclusion to his hit-or-miss Christian phase. Clydie King’s backing vocals, too, bring triumph to such a simple, waltzing ode to salvation.

15. “Desolation Row” (Highway 61 Revisited, 1965)

“Desolation Row” is one of the greatest acoustic songs of all time. I won’t try to spin it any other way. It’s a collection of great images and memories told with a sharp sense of surreal grace. The titular place is, according to Dylan, a “place in Mexico” that’s across the border and has a Coca-Cola factory. Al Kooper said that it’s a part of Manhattan’s Eighth Avenue that’s “infested with whore houses, sleazy bars and porno supermarkets totally beyond renovation or redemption.” The song is evocative of the Beat Generation, a cowboy song that, whether it was intentional or not, properly encapsulated where the 1960s in America would go after ‘65. Name-dropping Cain, Abel, T.S. Eliot, Einstein, Bette Davis, the hunchback of Notre Dame, Robin Hood, Dr. Filth and the Phantom of the Opera, Dylan paints a superhuman view of anti-escapism—where even when you’re young you’re old, and your greatest sin is your lifelessness. “Desolation Row” is humanity at its grimmest, sung beautifully by rock’s great, disinterested prophet.

14. “Abandoned Love” (Biograph, 1985)

Recorded just before the Rolling Thunder Revue tour began, Desire quickly became this stroke of genius existing in the shadow of Blood on the Tracks’s legacy. Dylan quickly perfected the protest song and the love song, but “Abandoned Love” is him at his most tortured: a man who has said every word imaginable but is now tasked with stringing them together in a way that might save his marriage or provide catharsis and clarity to its ending. “We sat in an empty theater and we kissed / I asked ya please to cross me off your list / My head tells me it’s time to make a change / But my heart is telling me I love ya but you’re strange.” It’s hard to tell what is more astonishing: that Dylan could write such a momentous and perfect depiction of heartache, or the fact that he had the gall to leave it off of a record altogether. “Abandoned Love” is the kind of track that makes Bob Dylan’s genius so influential in the history of modern music. To know his most popular songs is a gift, but to take the time to mine through the irreplicable gems, which come aplenty in numerous iterations across decades, is an act of loving discovery.

13. “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue (Alternate Take)” (The Bootleg Series, Vol. 7: No Direction Home: The Soundtrack, 2005)

No song shouts “the party’s over!” louder than “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue.” After getting booed off the stage at Newport in 1965, Dylan returned with his acoustic guitar to perform this song and “Mr. Tambourine Man” to an audience of unhappy bohemians. Too bad the sea had already parted and the names had been changed—the Bob Dylan they were getting then was long gone from the Dylan sold to them as the “spokesman of a generation.” How he beckons us to leave ourselves behind, to “forget the dead you’ve left, they will not follow you”—it’s maddening to sit with a song as painfully pretty as “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue.” This alternate take from the Bringing It All Back Home sessions is, to me, far greater than the performance that made the record’s final cut. The melody is ever-so-slightly more charming and Dylan’s voice doesn’t feel so brittled and strained. When I was in high school, I was obsessed with the “the empty handed painter from your sheets is drawing crazy patterns on your sheets” couplet; now, I find more refuge in the words that come after: “The sky, too, is fallin’ over you.”

12. “Can You Please Crawl Out Your Window? (Take 1, Alternate Take)” (The Cutting Edge 1965-1966: The Bootleg Series, Vol. 12, 2015)

I do believe that, had Dylan included “Can You Please Crawl Out Your Window?” on Highway 61 Revisited, it would be the no-doubt choice for the greatest album ever made. The song originally came out as a standalone single in December 1965, right after “Positively 4th Street,” and it was recorded with the Hawks backing him up just a few months before Blonde on Blonde sessions began. This is my favorite Dylan song of all time, thanks in large part to his poetry that unravels across it. Some of his greatest phrasings exist here, like “religion of little tin women,” “come on out, the dark is beginning,” “genocide fools” and “a fist full of tacks.” There is something righteous about “Can You Please Crawl Out Your Window?,” as Dylan makes his own language out of menacing fragments. “He looks so truthful, is this how he feels trying to peel the moon and expose it, with his businesslike anger and his bloodhounds that kneel?” he asks. “Are you frightened of the box you keep him in?” he doubles down. Before The Cutting Edge came out, “Can You Please Crawl Out Your Window?” had become a single lost to the sands of an era filled with so much material. The official recording of it isn’t worth the hassle; the alternate take of the first take of it, however, certainly deserves your attention.

11. “Shelter from the Storm (Live at Hughes Stadium, 1976)” (Hard Rain, 1976)

Dylan’s performance of “Shelter from the Storm” at Hughes Stadium in 1976 is one of the greatest live songs ever captured on tape. While I remain a staunch Hard Rain disciple and believe you could make a case for any of the nine tracks on it (especially the 10-minute rendition of “Idiot Wind”), I cannot look away from “Shelter from the Storm,” which Dylan delivers with the ferocity of a devout cynic. With a band of T Bone Burnett, Steven Soles, Rob Stoner, Howard Wyeth and Gary Burke behind him, it’s impossible to not be swept away by the passion in this performance. It’s a fantastic encapsulation of Dylan’s life at the time, as his divorce from Sara Lownds would be finalized the next year and the songs from Blood on the Tracks were becoming more and more punishing with every Rolling Thunder Revue date played. The razor’s edge Dylan sings about on “Shelter from the Storm” swells into an ensemble-driven synthesis of hard-nosed, loud, loose and rollicking anger, changing the meaning of the song entirely.

10. “You’re a Big Girl Now (Take 2)” (The Bootleg Series, Vol. 14: More Blood, More Tracks, 2018)

Originally stashed in-between “Simple Twist of Fate” and “Idiot Wind” on side one of Blood on the Tracks, I didn’t come to appreciate “You’re a Big Girl Now” until much later in my Dylan studies, when I heard the second take of it on the More Blood, More Tracks compilation in 2018. The distance between most Bootleg Series outtakes and demos and the final cuts is not entirely wide, but there is something so deeply perfect about this version of “You’re a Big Girl Now.” Dylan’s voice is closer to us, and his acoustic guitar is nothing more than an afterthought. His singing cracks, warbles, strains and thins out. Listening to him labor through the ache of lines like “I’m going out of my mind, ooh, with a pain that stops and starts, ooh, like a corkscrew to my heart ever since we’ve been apart” brings Blood on the Tracks into view like never before. When people say this period was Dylan’s best, the second take of “You’re a Big Girl Now” is exactly what makes them right.

9. “Precious Angel” (Slow Train Coming, 1979)

While the born-again trilogy wasn’t perfect, it made religious music sound cool. It wasn’t tedious or repetitive; Dylan welcomed something sensual into the work he made in that era. “Precious Angel” is one of the finest examples of that. Dylan recorded it with the great Jerry Wexler at Muscle Shoals, and, thanks to Barry Beckett’s subdued keys and the three-part, church-pew harmonies from Carolyn Dennis, Helena Springs and Regina Harris, it’s punctuated, bluesy and tactile. “Precious Angel” a gospel without the preaching, Mark Knopfler’s guitar playing is among his all-time best (an accomplishment, considering that “Sultans of Swing” had been released in America the same year as Slow Train Coming). “Precious Angel” is the born-again trilogy’s version of “Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again,” at least in terms of how Dylan sings certain syllables. It’s got the same sweeping intensity, distilled into the velvety chords of one of the greatest six-string pickers to ever live. Shine a light on me, indeed.

8. “Mr. Tambourine Man” (Bringing It All Back Home, 1965)

Before the Byrds cut three of the verses and fashioned it into a #1 hit, Dylan put “Mr. Tambourine Man” at the beginning of side two of Bringing It All Back Home. It converts the electric-fueled musings of side one into this grand, sprawling requiem of surrealism. Many have interpreted “Mr. Tambourine Man” as a paean about LSD, while others have pointed to religion as Dylan’s muse on the track. Nevertheless, some of the very greatest phrasings in the history of the English language are present right here. I won’t go through them all, because there are far too many to point out, but I would argue that these lines are the best: “Yes, to dance beneath the diamond sky with one hand waving free, silhouetted by the sea, circled by the circus sands, with all memory and fate driven deep beneath the waves. Let me forget about today until tomorrow.” “Mr. Tambourine Man” is Dylan’s gospel to the world.

7. “Standing in the Doorway” (Time Out of Mind, 1997)

When Dylan and Daniel Lanois were working on Time Out of Mind, Lanois suggested that Dylan rip himself off and “steal” the “feel” of “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands.” During the session, a dozen players came together to make the best song on the album without crowding the space. You can sense its density without feeling the weight of every layer, and Dylan’s lament anchors the gorgeous and gentle arrangement. Few songs about loneliness are as memorable as “Standing in the Doorway,” and there’s a sense of hurt that Dylan contrasts with a kind of grace tolls from the church bells. Whether or not “Standing in the Doorway” is an autobiographical song, it’s hard not to buy into the honesty Dylan presents on it. “Maybe they’ll get me and maybe they won’t, but not tonight and it won’t be here,” he sings. “There are things I could say, but I don’t. I know the mercy of God must be near.”

6. “Idiot Wind” (Blood on the Tracks, 1975)

I don’t think there’s a crueler song in the rock lexicon than “Idiot Wind,” a track that was once just an angry acoustic performance but plumed into this great, furious band-driven alchemy. But you come to “Idiot Wind” for the story—a scorched-earth diatribe against a wife: “You’re an idiot, babe, it’s a wonder that you still know to breathe” is a chorus I still yell to the heavens with a touch of regret. The final couplet—“We’re idiots, babe, it’s a wonder we can even feed ourselves”—is a perfect camera turned inward moment for Dylan, as he chastises a lover before holding his own suffering up to the light and kissing the sanctity of marriage and the doggedness of memory goodbye. Blood on the Tracks is one of the greatest albums of all time because of “Idiot Wind.” Bob Dylan is the greatest songwriter of all time because of “Idiot Wind.”

5. “Queen Jane Approximately” (Highway 61 Revisited, 1965)

Not only is it the best song on Highway 61 Revisited, but the opening piano/organ melody in “Queen Jane Approximately” is one of the most important, splendid sounds ever created. Kudos to you, Al Kooper, for playing a lick as fabulous as this one.

4. “Tears of Rage” (The Basement Tapes, 1975)

Co-written with the Band’s Richard Manuel, “Tears of Rage” is the Basement Tapes cut I am always returning to. A King Lear take on the Vietnam War written as conflict was escalating (1967) but released two months after its end (1975), it’s one of Dylan’s greatest and most political post-Another Side works. “Oh, what kind of love is this, which goes from bad to worse?” he sings in a raw-hemmed vocal, backed by the Band’s uncanny, falsetto harmonies and Manuel’s aching melody. “Tears of Rage” is what made Music from Big Pink one of the best records of its time, and it’s what makes The Basement Tapes such a treasure in Dylan’s lineage. And the song ends on one of his greatest lyrics: “Come to me now, you know we’re so low. And life is brief.”

3. “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right (Demo)” (The Bootleg Series, Vol. 7: No Direction Home: The Soundtrack, 2005)

Even if Dylan himself said in the Freewheelin’ liner notes that “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right” isn’t a love song, we can at least acknowledge that his then-girlfriend Suze Rotolo leaving for a stay in Italy profoundly affected him and his songwriting. He wrote a bunch of songs during that period, but “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right” is the greatest work of his career’s first lifetime. Before he went electric and ditched his protest-singer responsibilities, he made a statement on distance and on the challenges of love. “Where I’m bound, I can’t tell, and goodbye’s too good a word, babe” remains one of my favorite Dylan couplets. I think the demo version of this song, which can be heard in No Direction Home, is superior to the Freewheelin’ recording. There’s an extra touch of sweetness here, even when Dylan is at his most bitter.

2. “Changing of the Guards” (Street-Legal, 1978)

There are very few instances in Bob Dylan’s catalog where he sounds better than he does here, on “Changing of the Guards.” I think these are six of the greatest minutes in all of music history. “They shaved her head, she was torn between Jupiter and Apollo,” Dylan sings at one point, and later he offers one of his greatest verses: “The palace of mirrors where dog soldiers are reflected, the endless road and the wailing of chimes, the empty rooms where her memory is protected, where the angels’ voices whisper to the souls of previous times.” The three-part backing vocals from Carolyn Dennis, JoAnn Harris and Helena Springs transform the song into this meadow of echoing gospel excellence, while Steve Douglas’s tenor saxophone imbues the melody with a warm, colorful turn of phrase. It’s a big-time rock beat and seismically paradoxical, segueing in and out of first- and third-person storytelling that, according to Dylan himself, “means something different” every time he sings it. “‘Changing of the Guards’ is a thousand years old,” he declared. Yet, every time I press play on it, the song hits me anew.

1. “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands” (Blonde on Blonde, 1966)

A few months before he started writing what would become Blonde on Blonde, Bob Dylan secretly married Sara Lownds. Their first child together, Jesse, was born in January 1966, and “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands” is a beautiful, biblical ode to the two of them—especially Sara—composed during an eight-hour stupor on a dead-air Nashville night. I do believe that this is not just Dylan’s greatest song, but, simply, one of the greatest songs any living being has ever written. It is a combination of everything that makes songs like “Desolation Row,” “Mr. Tambourine Man” and “Like a Rolling Stone” so revered—this collision of tranquil melody and esoteric, oft-absurd and poetically abundant lyricism. There are five verses on the song, each delivered with some of the sharpest phrasings of Dylan’s career. I won’t go on and on about them, but “magazine-husband,” “into your eyes where the moonlight swims,” “your cowboy mouth and your curfew plugs” and a “mercury mouth in the missionary times” deserve mentions. There is nothing flashy about “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands”; it is a track as splendid and profound as it is small and protected. When Dylan called his bandmates into the studio at 4 AM, they played and played—with minimal guidance—until they came out with an 11-minute song that, according to Dylan, they all nailed on the first take. But what speaks loudest to me about “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands” is that, even after eclipsing the 11-minute mark, Dylan served us his entire world—the gate where his warehouse eyes met Sara’s ghostlike soul, the bowery where they both still wait.

Matt Mitchell is Paste’s music editor, reporting from their home in Northeast Ohio.