Bob Mould: The Sun Shines Through the Apocalypse

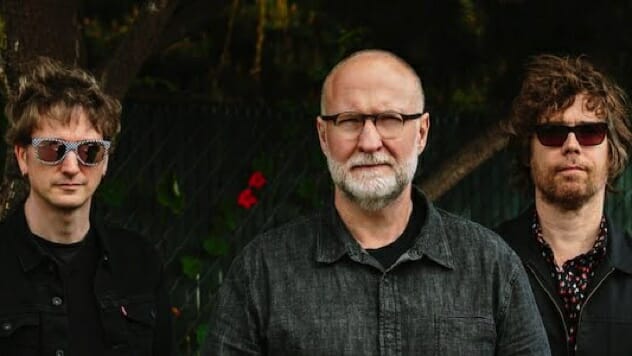

Photo courtesy of Merge Records (from left: Jason Narducy, Bob Mould and Jon Wurster)

The title track to Bob Mould’s new album, Sunshine Rock, opens with his signature guitar sound: that brisk succession of dense, beyond-triad rhythm chords that overlap with long-decay reverb and accumulate into a storm of sound that’s easily heard as a storm of feeling. They may be delivered with percussive force, but threading through them is always a melodic line that reinforces the emotion.

It was the sound of 1980s hardcore, which grew out of punk and soon morphed into grunge, a sound that Mould more or less invented for his first trio Hüsker Dü and continued to refine for Sugar and his solo recordings. It was one of the great rhythm-guitar innovations of the rock ’n’ roll era, right up there with those of Chuck Berry, Jimmy Nolen, Keith Richards, Freddie Stone, Roger McGuinn, Nile Rodgers and Johnny Ramone.

“Because I started in a three-piece,” Mould says, “I had to learn how to fill out the sound by myself, that Pete Townsend thing of having to play lead and rhythm at the same time, like Richard Thompson. It’s an art form that not a lot of people use today.”

In the popular imagination, Mould’s guitar attack is associated with the anger and angst of punk-rock—and not without reason. Punk was the perfect vehicle for venting youthful discontent, and bands from the Sex Pistols to Hüsker Dü to Nirvana did just that. So it’s a surprise when the lyrics to “Sunshine Rock” come into focus. “I’ll bring you with me into the sunshine rock,” Mould cries over his roiling guitar. “We watch the fireworks and stay so late we miss the train.” The major-chord melody is infectious, and in the song’s second half, the strings of the Prague TV Orchestra swell from underneath to make the buzzing guitar harmonies even denser.

“That guitar sound is my standard delivery model,” Mould points out. “Not to shortchange the Prague Orchestra, but that guitar approach is my signature; it defines the record. But it’s not like I’ve never used that sound with upbeat songs before. Think of Flip your Wig and F.U.E.L.”

Indeed Hüsker Dü’s Flip your Wig and Sugar’s File Under Easy Listening proved that the fast/hard ethos of punk could be applied to happiness as effectively as unhappiness. Even many of the Ramones’ early songs boasted a gleeful brattiness. Mould’s guitar sound is agnostic; it will intensify any feeling, whether positive or negative.

Listen to a Bob Mould solo show from 1996:

“I started writing this album at the end of 2016, over in Berlin,” he says. “It was pretty dark and wintery—the darkest, most wintery thing I’ve ever experienced. It was worse than even Minnesota. Yeah, Minnesota is really cold and gets a lot of snow, but the ground is white so you get a lot of reflected sun; it’s often very bright outside. In Berlin, it’s as if the clouds are hanging ten feet over your head, and it’s dark for months. I missed the sunshine.”

After spending most of the ’90s in New York City and most of the ’00s in Washington, D.C., Mould moved to San Francisco in 2009. Since 2016, he’s been splitting his time between Frisco and Berlin. He has always maintained that his environment influences his songwriting, and that was especially true for this album. “It’s a long way from California to Berlin, so filled with melancholia” he sings on the new album. “Winter came and paralyzed me…. I’m like a polar bear crawling through the tundra.”

“It was in the midst of all that darkness that ‘Sunshine Rock’ tumbled out during a writing session in 2017,” he continues. “When it fell into my lap, I said, ‘Maybe that would be a good place to write from, a more optimistic point of view. Maybe that could be the basis of the next record.’ You know my previous work; I’m not always so optimistic, so I had to constantly remind myself to stick to the agenda.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-