Chloë and the Next 20th Century Is Father John Misty Like You’ve Never Heard Him Before

On his fifth record as Father John Misty, Josh Tillman cedes center stage

A decade or so ago, Josh Tillman created the Father John Misty character after he realized how much more people paid attention to his stage banter than his songs, recorded then under the name J. Tillman. “I could see the audience come to life,” he said in 2012. “Their eyes would light up and they were listening and captivated, and then I would start playing … and their eyes would glaze over.”

That experience, which happened over and over again as he released eight albums that were pretty much ignored completely, led him to create the persona that the audience was actually responding to, this time as the singer/songwriter himself, not just the pseudo-stand-up comedian performing between the melancholic folk songs.

But whether through unnamed major life events or simply personal growth, Tillman outgrew Father John Misty at some point during the Pure Comedy press cycle, when he was the most visible and talked-about indie musician on the planet. The vast majority of the qualities that made Father John Misty such a lovable, yet cynical songwriter were gone by 2018’s God’s Favorite Customer, his first album without the extra snark.

Fast-forwarding four years to the present day, Father John Misty is basically nowhere to be seen on Chloë and the Next 20th Century. Tillman sounds like a completely different artist from the one who wrote “The Night Josh Tillman Came to Our Apt.”—and that’s not a bad thing. After the many layers of irony and satire have been stripped away from his songwriting, we’re left with the prettiest and most heartfelt collection of songs he’s released to date.

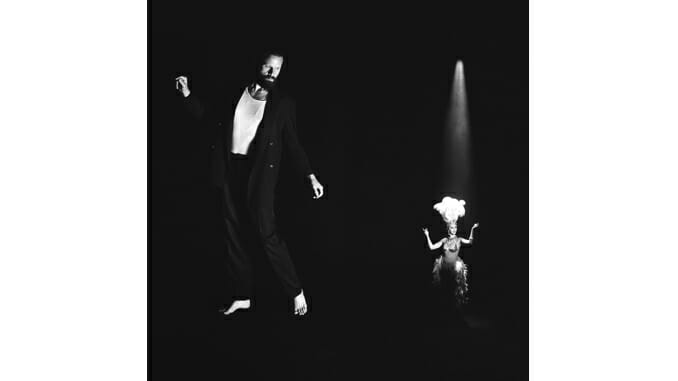

The differences between Chloë and the rest of Father John Misty’s discography are immediately apparent: Album opener “Chloë” begins with old-timey horns before launching into a 1920s-esque big band track that sounds like some long-lost entry in the Great American Songbook. It wouldn’t be surprising to see Tillman bust out a top hat and tap shoes for some of the instrumental breaks at any of his upcoming shows where he’ll be playing with full symphonies.

Though “Chloë” is a major departure for Tillman musically, it also represents some of his most vivid storytelling thus far, telling the tale of his narrator’s relationship—unclear whether romantic or not—with Chloë, “a borough socialist” who likes “drinks with a certain element of downtown art criticism.” The details are strong throughout, from the specific (“How you could have dropped the cigarette on the trip your boyfriend’s canoe flipped”) to the metaphorical (“Her soul is a pitch black expanse”). It all ends with one of the most heartbreaking and striking images in Father John Misty’s discography, Chloë’s apparent suicide: “Summer ended on the balcony / She put on Flight of the Valkyries / At her 31st birthday party / Took a leap into the autumn leaves.”

Those two main strengths of “Chloë”—the expanded instrumentation, complete with a full orchestra, and a new propensity to tell stories with vivid detail, absent any hint of that trademark snark—are what makes the whole of Chloë and the Next 20th Century such a songwriting triumph that continues to reveal more about itself upon each listen. Fans of Father John Misty’s past, more straightforward tracks, from the heavier “Hollywood Forever Cemetery Sings” to the catchy folk-rock of “Total Entertainment Forever,” might be disappointed at first to hear a full album that takes after Randy Newman, or the kind of songs that would’ve soundtracked a Gene Kelly dance routine. But let its full beauty sink in, and there’s just so much to love here.

Though we’ve heard some indie favorites experiment with strings lately—think Angel Olsen’s All Mirrors, Radiohead’s A Moon Shaped Pool or Tillman’s old band Fleet Foxes’ Crack-Up—Father John Misty is the first of the bunch to fully commit to it. Chloë isn’t one of those “Oh, they added strings!” albums—it’s a full-blown symphony record where each instrument gets its time to shine. It’s still largely set to the backdrop of Misty’s ‘70s-indebted folk-rock, but it just feels like such a leveling-up by an artist who has been the standard-bearer of his genre for a full decade now.

Take “Q4,” for instance, perhaps the closest thing to a prototypical Father John Misty song on Chloë. The arrangement on “Q4” sounds like something entirely new to his catalog, like an expansive track that’d fit in some golden-age Western—or at least a Tarantino one. Propelled by harpsichord and a gorgeous string section that takes center stage on the bridge, Tillman’s voice soars as he imagines a writer named Simone Caldwell who stole the story of her memoir from her deceased sister. He takes a shot at the press—something he has loads of experience with—and publishers both, who say the book was “just the thing for their Q4 / ‘Deeply funny’ was the rave refrain.”

Chloë’s music offers more variety than ever before—just look no further than the song that follows “Q4,” “Olvidado (Otro Momento),” which sees Tillman experiment with bossa nova. Going from the wide-open plains to the beaches of Brazil, the transition shouldn’t work as well as it does, but the orchestral backing behind Tillman’s voice works wonders, particularly the fluttering piano and the woodwind section. Elsewhere, lead single “Funny Girl” would fit alongside any slower Tony Bennett classic, while the strings on “Only a Fool” would feel right at home on the score for Toy Story or even Ratatouille.

Perhaps the most understated instrumentals on Chloë are its most striking: The piano at the beginning of “Kiss Me (I Loved You)” is almost identical to that on “I Love You, Honeybear.” Yet on its sonic relative, seven years after the fact, there’s no driving percussion to propel it to an anthemic love song. Tillman’s beat up after the marital strife that marked God’s Favorite Customer, his voice shaky, distorted and distant. Gone are the “mascara, blood, ash and cum on the Rorschach sheets where we make love,” and it feels as if he’s now on the other side of the “Everything is doomed and nothing will be spared” refrain. Now, broken and emotionally spent, he simply pleads, “Kiss me like long ago,” before admitting, “Our dream ended like dreams do / But kiss me / I loved you”—note the past tense.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-