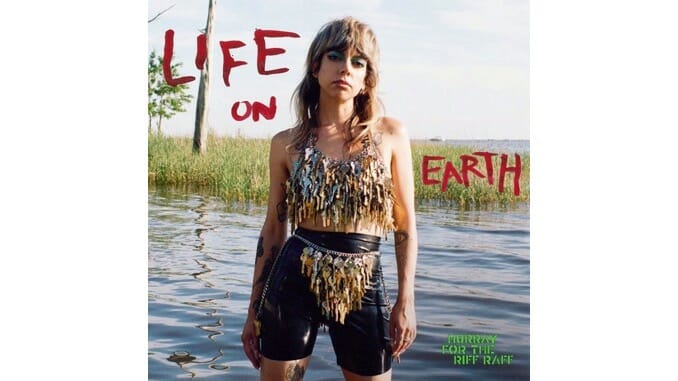

Hurray for the Riff Raff Finds New Life on Earth

The New Orleans folk artist gives audiences hope and survival tools on their latest album

Reinvention happens. Artists evolve over time, all the time: Against Me!, for instance, or Taylor Swift, or Joni Mitchell. Life on Earth, the seventh album by New Orleans-via-New York folk-blues-punk project Hurray for the Riff Raff, qualifies as reinvention on the same level, with a caveat: Singer/songwriter and frontperson Alynda Segarra has taken such leaps over the last decade and a half as a human being, as well as a musician, that their efforts on Life on Earth express reinvention less than they do rebirth. It’s rare for a record so deep in a band’s discography to function as a fresh start after establishing a style, not to mention a personality, over so many years.

Segarra pulls off that trick in part because Hurray for the Riff Raff’s last album, The Navigator, did heavy lifting setting the stage for change. On The Navigator, Segarra wrestled with their Puerto Rican heritage in transition after seamless transition from track to track, stringing together a tight, cohesive story about their background and the weight it lays on their shoulders; through each song, they considered Puerto Rico and their Puerto Rican-ness, and the responsibility they have to both as a child of the country and as a musician. That’s a big damn burden for one person to carry, but Segarra carried it with their own strength and their band’s combined strength, too-Casey McAllister, Dan Cutler, Sam Doores and Yosi Perlstein. Now, they carry that burden through to Life on Earth.

Seventh acts aren’t often this urgent or original. We’ll never know because we don’t live in an alternate timeline where Life on Earth is Hurray for the Riff Raff’s debut, but if you hear it without knowing the author, you might guess it’s the product of a new act instead of veteran talent. Obviously, you’d be wrong, but therein lies the album’s raw power as an act of awakening: With Segarra’s newfound sense of self and a new outlook on life and the world comes a new sound, and a new mission, both related to the old but attuned to the moment. Music is slightly better positioned to pick its time than, say, film and TV; had COVID never happened, Segarra might have made a different record than Life on Earth. But COVID is still happening, and so Life on Earth reads as a reaction to its effects on American life.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-