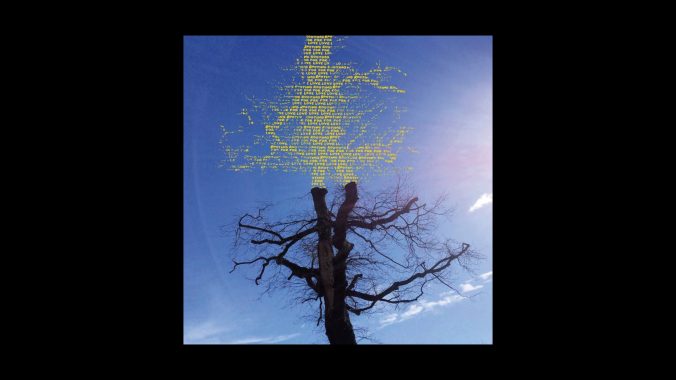

Laetitia Sadier’s Rooting for Love is a Transcendental Treatise on Healing

The Stereolab vocalist's fifth album verges on New Age frippery, but there’s an earnestness and even a level of chaos to the record that sets it apart as her best since her debut 14 years ago.

Over the last decade or so, the term “self-care” has quietly become one of the most egregious buzzwords in popular culture. Though originally coined as a medical term in the mid-century, the phrase was popularized in the 1960s by key women of color as a political term. Angela Davis and Ericka Huggins began meditating while sitting in jail cells; Audre Lorde wrote about self-care as an act of “self-preservation” and “political warfare.” To the disenfranchised and the radicalized, self-care is just as much a labor as direct action—it’s a restorative practice where we give ourselves the things we are systemically denied: education, time to reflect, healing from trauma and taking care of our bodies as an extension of our minds. Self-care may imply this is a solitary exercise, but only through communal care are we able to actualize any of this; after all, these are things denied to us on an individual level, so these resources are only made available when shared.

The synthesis of politics and spirituality have come to be seen as something distinctly feminine in our modern times, often because of the masculine, heterosexual bent Western leftism has taken in the new century. Spiritual growth is seen as superfluous, indulgent, and individualist. Change is only achieved through external disobedience. Laetitia Sadier has always rejected this notion. Born in 1968, she grew up in a conservative family and discovered the power of collective action in the late ‘80s after moving to London to pursue her music career—wedging her early life neatly between the rise of the New Left and the advent of third-wave feminism. Sadier recalls that even the men within her circle brushed against the riot grrrl movement.

-

-

-

-

-

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 3:10pm

-

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:57pm

- Urls By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:57pm

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:55pm

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-