Lindsey Buckingham on Going His Own Way

The rock legend discusses his first new solo album in a decade, its roots in Fleetwood Mac's '70s/'80s heyday, and the "raw nerve" in his songwriting

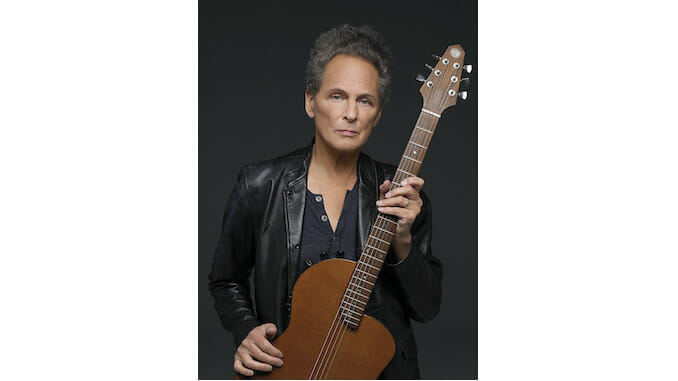

Photo by Lauren Dukoff

This summer’s single “On the Wrong Side” sounds like a long-lost gem from Fleetwood Mac’s heyday in the ’70s and ’80s. It has all the hallmarks of that period: confessions of ill ease while “living life in overload,” the lyrics counteracted by sumptuous three-part, male-and-female harmonies, and melodic guitar motifs, all over a no-nonsense propulsion at the bottom.

But not only does the song come from this year’s Lindsey Buckingham, the musician’s first solo album in 10 years, but he also recorded every vocal and instrument himself. He even did the female-vocal parts by raising the pitch of his voice with help from a variable speed oscillator. It’s proof positive that the chief architect of Fleetwood Mac’s four classic studio albums—Fleetwood Mac, Rumours, Tusk and Tango in the Night—can still summon that sound at will. He even admits that this new tune is the musical sibling of his earlier signature song, “Go Your Own Way.”

But Buckingham doesn’t always want to work in that vein. “I wanted to make a pop album,” he declares in the album’s press materials, “but I also wanted to make stops along the way with songs that resemble art more than pop.” And indeed, most of the album is devoted to more stripped-down arrangements with quirky blends of acoustic and electric instruments over simple drum loops and layers of breathy vocals. The melodies are always hooky and the harmonies always sumptuous, but the minimalism makes them sound more like chamber-rock than the arena-rock of his old multi-platinum band. And he’s fine with that.

“When I’m in the band mode,” Buckingham explains over the phone from his Los Angeles home, “recording an album is more like moviemaking. You bring in your song like it’s a script, and you have to verbalize to the actors and crew what you want done with it. And it becomes a cocktail of everyone’s contributions. The budgets are bigger, and everything is more political. When I’m in the solo mode, it’s more like painting. The song doesn’t have to be as fleshed out when I go into the studio. I can be alone and slop paint on the canvas. I can let the paint speak to me, as well as me speaking to it. The song can come to life while you’re working on it.

“I tried to introduce some of that process into Tusk,” he recalls. “It was a line I drew in the sand to protect us from commercial considerations. But when that album didn’t sell as well as the previous one, it became difficult to maintain that experimental approach. That’s why I started doing my solo projects, so I would have an outlet for that side of my music. It’s a tradeoff: You gain some freedom, but you lose a lot of the audience.” At this point, he switches metaphors. “It’s like Jim Jarmusch, who makes movies with the freedom of experimentation, but he knows that they will never have an audience like Steven Spielberg’s films.”

“I Don’t Mind,” the first single off Buckingham’s solo album, resembles a Jarmuschian indie film more than a Spielbergian/Fleetwood Mac blockbuster. The opening blend of hushed voices and prodding guitar relies more on mesmerizing atmosphere than conventional exposition. The lyrics are a succession of tantalizing fragments, rather than a linear narrative or monologue. This small-scale song works because Buckingham doesn’t rely on a single hook, but creates two hooks for the lead vocal, two different hooks for the backing vocals and two more for the lead guitar, all locking together like puzzle pieces.

Buckingham insists he doesn’t want to limit himself to only making small, experimental records or only making big, commercial records. He likes doing both. If he had had his way, he would still be in Fleetwood Mac, joining their recordings and tours, and working on his solo projects in between. But when he had the album Lindsey Buckingham almost ready for release in 2018, he asked his bandmates to delay their tour for three months so he could do a solo tour behind the project. Instead, they fired him from the band.

Stevie Nicks, who was Buckingham’s girlfriend from 1967 to 1976 and his bandmate from 1967 to 2018, claims she didn’t fire him, but rather fired herself, forcing the other band members—Mick Fleetwood, John McVie and Christine McVie—to choose between the feuding exes. Nicks possesses the greater commercial sway, and the band members went with her—which makes sense if you’re mounting a nostalgia tour of your biggest hits. Buckingham told the L.A. Times that Christine McVie later emailed him to say, “I’m really sorry that I didn’t stand up for you, but I just bought a house.”

When she was less worried about her mortgage and more worried about making a new album, she reached out to Buckingham to massage her songwriting into Spielbergian pop singles as he had so often in the past. Those sessions were released in 2017 as the delightful album Lindsey Buckingham/Christine McVie, featuring five lead vocals by each of them. but there had been hopes that these songs might have become a new Fleetwood Mac album.

“Before Christine rejoined the band in 2014,” Buckingham says, “Mick, John and I had already gone into the studio in 2013 with producer Mitchell Froom to cut some songs of mine. We finished them except for leaving room for Stevie’s voice. But Stevie wasn’t interested; I think she didn’t have any new material and felt bad about it. So that album didn’t happen, but Stevie did pull out an old song, so we put out an EP with three of my songs and that one of Stevie’s, and we went out on tour as a four-piece.

“When Christine came back, we had these songs left over from the Mitchell Froom sessions, plus some new songs I’d written. Christine was sending me songs she had written, and I was working on them in my studio. I sent her some tracks with melodies that I was working on, and she put words to them. We were hoping that when Stevie heard what we were doing, it would draw her in, but she wasn’t interested. So we released it as a duo album.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-