Time Capsule: Paul Simon, The Paul Simon Songbook

Every Saturday, Paste will be revisiting albums that came out before the magazine was founded in July 2002 and assessing its current cultural relevance. This week, we’re looking at Paul Simon’s proper debut album, which boasts a tracklist of songs that would live stronger lives elsewhere yet make for a vibrant, stripped-down introduction to one of the greatest songwriters of our time.

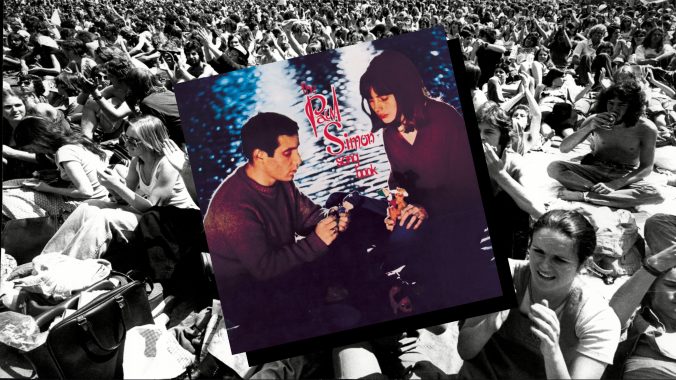

Photo by David Thorpe/ANL/Shutterstock

At 15, I started “dating” a cute girl who lived two towns over—which, when you don’t have a driver’s license, is practically like living on opposite coasts. All we did was text and send Snapchats to each other, fully embracing how the origins of social media were colliding with the onset of a new and hopeful and terrifying age of being terminally online. We were sketching our digital footprints in real time, drawing pictures of each other and flirting like such small gestures of affection would soon go extinct. She was my #wcw and I was her #mcm and, after getting my first iPhone, I spent a $20 iTunes gift card on my first album: The Paul Simon Songbook. I bought it because of “Kathy’s Song,” which the girl from two towns over and I had declared to be “our song”—which meant we’d send lyrics to each other almost daily, holding the words sacred like wedding vowels. But time back then, it moved like wildfire and, in the stroke of a month that felt like the flash of a day, she ghosted me and started dating my best friend—who was a year older than me and had his license and could mend the gap of distance without a hitch. “I stand alone without beliefs, the only truth I know is you” indeed.

Before I would watch The Graduate and make “plastics” my entire personality sometime in 2014, I found a softened palate of unproblematic folk music in The Paul Simon Songbook. Many of the 12 songs would end up on Simon & Garfunkel records eventually, but they were Paul Simon’s debut darlings first. Recorded and released in between the Simon & Garfunkel albums Wednesday Morning, 3 A.M. and Sounds of Silence, The Paul Simon Songbook was Simon’s attempt at recalibrating after the former sold poorly. He made the record at Levy’s on New Bond Street in London, having traveled to Europe frequently to perform at clubs around Paris, Copenhagen and Haarlem. The process of making Songbook was daunting, as he only had a single mic for his voice and guitar, often having to do multiple takes just to get one track right. Simon took two songs from Wednesday Morning, 3 A.M.—“The Sound of Silence” and “He Was My Brother”—and re-recorded them. It was a messy affair that, against all odds, ended with one of the most saccharine and under-loved folk records of its time.

While The Paul Simon Songbook came out in 1965, it was only initially released in the UK—and it didn’t see a US release until its inclusion in the Paul Simon: Collected Works box set in 1981. Even today, Songbook doesn’t carry the same strong foundation of listeners as Simon’s later work, like Still Crazy After All These Years or Graceland. This was Simon at his rawest, and his potential had not yet been properly discovered. “The Sound of Silence” had not yet become a quiet anthem of an entire generation, as Simon & Garfunkel were, simply, a duo once known as Tom & Jerry and rather unproven. They were not yet titans of the New York folk scene, and Paul Simon was certainly not lauded as one of the best penmans of his era. I am a sucker, though, for a charming introduction, and Songbook is that and more. Tapping into this rendition of “The Sound of Silence,” it’s easy to see that, if the dominos fell differently, Simon very well could have just been another folk singer lost to the sands of time oversaturated by Bob Dylan’s dominance—a realm of forgottenness populated by heads like Fred Neil, Dave Van Ronk, Patrick Sky and Carolyn Hester.

But of course, we know how the story goes. Simon would write a lot of songs while in England in 1964 and 1965, and many of them, like “Homeward Bound” and “For Emily, Whenever I May Find Her,” would form his and Art Garfunkel’s breakout record Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme in 1966—which would then crack open the floodgates for the duo on Bookends and “Mrs. Robinson” two years later. The Paul Simon Songbook is the epitome of a stepping stone, as nearly all of its songs have lived stronger lives elsewhere. But still, these songs are beautiful and unkempt and transcendent. It sounds like Paul Simon walked into a studio and sang into the first microphone he found, unbothered about whether anyone else was there to hear or tape him.

On “Flowers Never Bend With the Rainfall,” we’re met by the sound of a busker given room to spread out—but he doesn’t put his arms out too far. Simon is a torchbearer of restraint, never overworking the songs for the sake of flamboyancy or genius. It’s just his voice and a guitar, as he toes the line between easy-listening and thought-provoking. “The mirror on my wall casts an image dark and small, but I’m not sure at all it’s my reflection” being a lyric on a singer-songwriter’s debut album still radiates. The glow of Songbook never dims when Simon sings, his language a vibrant stenograph of a mid-20s performer still coming of age yet lilting like a middle-aged troubadour.

And while, yes, you could just go listen to any of Simon & Garfunkel’s five studio albums instead, I can’t help but, nine times out of 10, return to The Paul Simon Songbook. As I’ve grown older, Simon’s barebones rendition of “A Most Peculiar Man” is the curiosity that pulls me back in more and more, as he plucks ever so gently on his guitar and airs out a splendidly tender vocal, singing “He had no friends, he seldom spoke. And no one in turn ever spoke to him, ‘cause he wasn’t friendly and he didn’t care and he wasn’t like them.” A 24-year-old fashioning such a devastating story about a recluse, with such a lived-in concept of mortality in tow, is so fleetingly rare—yet Simon will have you convinced he’s worn out enough lifetimes to have the nuance to proselytize such singular narratives. Likewise, on “I Am A Rock,” Simon has something to say about his emotions and why he’s guarding them. “Don’t talk of love, well I’ve heard the word before,” he sings. “It’s sleeping in my memory, I won’t disturb the slumber of feelings that have died. If I never loved, I never would have cried.” Simon’s voice, though not as conventionally beautiful as Garfunkel’s high-register ascent, is plaintive here, only coiling around a lightened, running prettiness when absolutely necessary.

“Kathy’s Song” is Simon’s first track where he explicitly calls out his then-girlfriend and momentary muse Kathy Chitty (who appears alongside Simon on the album’s cover, as they sit on a cobblestone street in London while holding wooden figurines), whom would inspire the song “America” a few years later. 60 years later, I fear that Simon has failed to write lines as beautiful as “And as I watch the drops of rain weave their weary paths and die, I know that I am like the rain, there but for the grace of you go I.” “Kathy’s Song” features one of Simon’s best guitar performances, a moment of delicate finger-picking that precisely matches the ingenuity of his own singing.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-