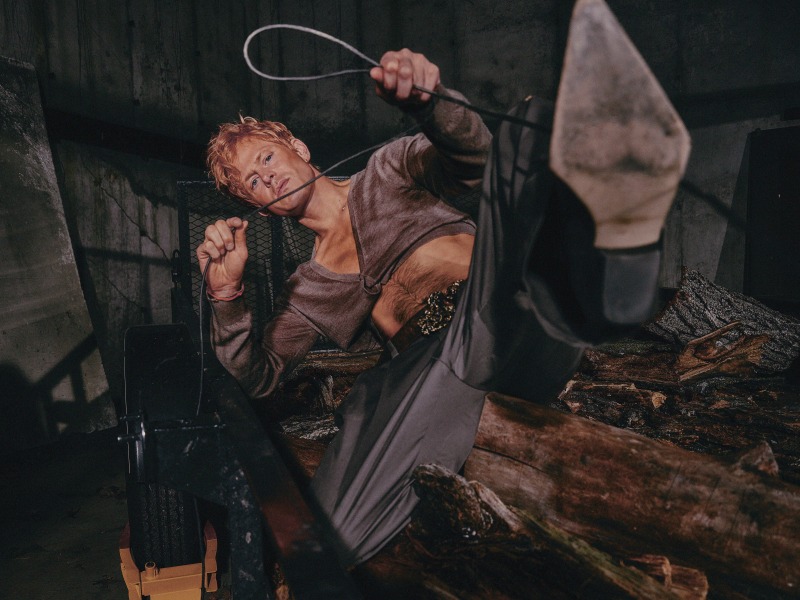

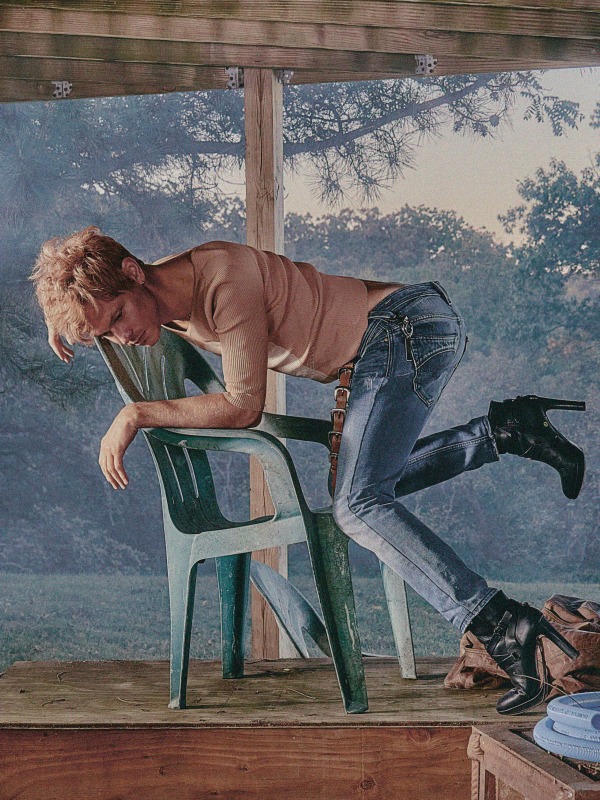

COVER STORY | The Everything of Perfume Genius

In our latest Digital Cover Story, Mike Hadreas talks about accepting death, the intimacy of counterbalance, art mirroring queerness, getting braver in the studio, working with Aldous Harding, and the full-band collaboration powering his seventh Perfume Genius album, Glory.

Photos by Cody Critcheloe

Hearing PJ Harvey’s “The Dancer” for the first time, I knew “He said, laugh a while, I can make your heart feel” would remain within me. There’s a moment like that on Glory—the new Perfume Genius album—too, when Mike Hadreas sings, “Time, it makes a clean heart when you’re miles away from it all and the dream is gone.” The cord that binds To Bring You My Love and Glory is an unintentional one, but it’s not lost on me that, while doing press for Set My Heart on Fire Immediately in 2020, Hadreas told Vulture that Polly Jean had been a great influence on those songs—specifically, it was her 1995 opus, which he wrote scandalized and empowered him. “I love just seasoning the air with something darker and nastier,” he said, “and I like just staying there for a while.”

And it’s not lost on me that today, thanks to lingering jetlag, a case of norovirus and our paralleled cross-country and intercontinental traveling, my conversation with Hadreas is happening on February 27th, the date commemorating To Bring You My Love’s 30th birthday. I mention the coincidence to him. “When you’re young, albums change that whole time for you—how you look at everything, how you’re operating,” he replies. “I think [To Bring You My Love] still does that for me but less, especially now that I do it myself.”

The first Perfume Genius album, Learning, came out in 2010. I didn’t hear Hadreas’ music until 2012, when he made Put Your Back N 2 It, and I didn’t fully understand that I was queer until after he released Too Bright two years later. But it was in 2017, during the first bloom of May, that I came out for the first time, in the rattling hours of my second college semester, mere days after Hadreas sang “They’ll never break the shape we take” to me and so many others. What he says about To Bring You My Love—about the albums you love when you’re young—my goodness, if that’s not Perfume Genius’s catalog for me. And, hey, maybe it’s that for you, too. As Aldous Harding wrote on Instagram last month: “So wretched I did need him from the moment I heard him.”

But I’m not in college anymore, no longer surrounded by people three or four years my senior showing me how to live a non-binary life just by inviting me into their conversations. The first part of your life is undoubtedly hard, but it’s also beautifully easy. A song like “Dreeem” taught me that, when Hadreas sang “You were there, you still knew my name, and you still held me exactly the same way” into the air of a piano melody. When you are young, there are people and there is art ready to guide you into the next chapter of yourself, even if it takes a small lifetime to find them. I’m closing in on 30, and I’m having to figure out how to live through what I remember. My sexuality and gender are growing stranger and more disgusting, but the language for it is rarely new.

Hadreas, now 43, is craving examples of what he could be less, instead yearning for a mirror to how he is. “I think I just want to feel good. I want to feel happy. I want to feel excited. I want to cry. I want to feel everything as it is, but not because I figured it out—or because I finally fit into something that I’ve always been trying to, or think that I’m supposed to,” he tells me, before pausing. Chuckling, he continues: “I’m gay, you know?” We both laugh. “I’ve heard rumors about this,” I say. He replies, “When I was four, they were like, ‘You’re gay.’ And I’m like, ‘Oh, what is that?’ And then I researched it and I was like, ‘Oh, I guess, yeah, I’m gay.’ I did that for a very long time, and I am still doing it, but I wonder what I would have thought about everything if nobody told me.” It’s refreshing to hear Hadreas talk about existing in coming-of-age’s afterword.

What Glory is, at least in the queer canon, is a picture of Hadreas no longer “trying to be a gay man.” “There’s parts of [being a gay man] that I like, and there’s parts that I’ve definitely figured out,” he continues, “but when I stopped trying to figure that out, I felt less like one—in a way that feels more like me. It allowed me to think, ‘Well, if I’m not a gay man, what else is there?’” What he found was expansiveness, and an identity that is simultaneously curated, intentional and unchangeable. “I don’t know when I stopped trying to figure it all out—in some ways, it made it more confusing. I feel like I’m thinking a lot more about all of this stuff. Weirdly, even though I’ve written five albums about it, I feel like I’m thinking about it more now, but in a way that doesn’t feel so EMERGENCY! EMERGENCY! Who are you??? It feels more like, ‘Well, let’s think about this.’”

Glory is 11 feelings with 10 ideas inside each of them. Hadreas takes a generous but mathematical approach to his songwriting, identifying what place he needs to zoom out from just so he can access the exact thing he’s trying to share with everyone else. “It starts with a soup of stuff, and then I have to portion it out and make counterbalance and choreography,” he explains. “I don’t know if it’s coming purely from a directly confessional thing. It feels like it’s just for me.” Hadreas doesn’t listen to his recordings very often, but he has a close relationship to his demos, especially the ones that never become Perfume Genius songs. “I don’t need to write the whole screenplay. It could just be five words, but I know the whole screenplay inside me. I get a feeling from it when I’m listening to it. I don’t have to finish it.”

The Glory title track is only 12 words long (a formula not uncommon for a Perfume Genius song). There’s a phrase within it—“guest of body”—that stuck with me after my first listen. Hadreas says that, when he wrote the song, he was thinking about the soul “before, during and after you’re alive.” Death has been on his mind, especially since the COVID pandemic. “I really know I’m gonna die,” he admits. “It’s not an idea to me anymore. And I feel like [my partner] Alan [Wyffels] is gonna die, my mom is gonna die—in a way that is very new. I know it’s, at some point, gonna happen, but surely not soon, or now, or all of a sudden. But that’s been really hard for me to process.” Hadreas feels tender about “Glory,” and he considers it to be, really, about our spirits being shepherded to the “next place,” saying, “I’m trying to be sweet about the whole thing, not so protective. I can still have love and sweetness when it’s not in the body. [I’m] trying to think that way about everything, instead of being so paranoid all the time about an accident or a global event.”

“Left For Tomorrow” is full of worry, inspired by Hadreas grieving the premature loss of his still-living mother. “Back where the light is streaming, I carry it on my shoulders without her,” he sings, against a current of snare pops from the great Jim Keltner, synths from Alan Wyffels and touches of Pat Kelly’s upright bass. But “Left For Tomorrow,” six months after it was written and finished, became a song for Hadreas’ chihuahua named Wanda, who had just passed away. (Glory is dedicated to her memory.) I am so often in awe of how he writes about absence and how his records always leave room for love even in vacancy, even in the gross, metallic and wrenching horseplay of “Hanging Out”’s final verse (“I see his body loosening / The jaw hangs like circuitry / I’m four on the floor in the dirt / I’m chewing his face like a hog”) or the scribbled, pastoral ballet of “Capezio” (“Flat on her back / With a tongue in her armpit / She told an insane joke / Only I followed”).

We get that space in Glory because of the band Perfume Genius has become. And Glory is a band record, even if not in the obvious sense. Perhaps a person wiser than me could find similarities between these songs and Black Sabbath or the Cardigans, or something, but the contributions from Tim Carr, Keltner, Meg Duffy, Blake Mills, Kelly, Greg Uhlmann and Wyffels are so sweeping and radical, making the album one of the most collaborative efforts Hadreas has ever entered into. On the last few Perfume Genius albums, the demos Hadreas brought to Sound City were fuller. “All the things I wrote in isolation had lots of harmonies or synths,” he says. “I really go in and build a world before I even get to the studio. And in the studio, it can be completed. We can scrap everything.” Glory doesn’t have any sounds from Hadreas’ demos inside of it, because every rough sketch featured only piano, vocal and maybe a stray harmony here or there.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-