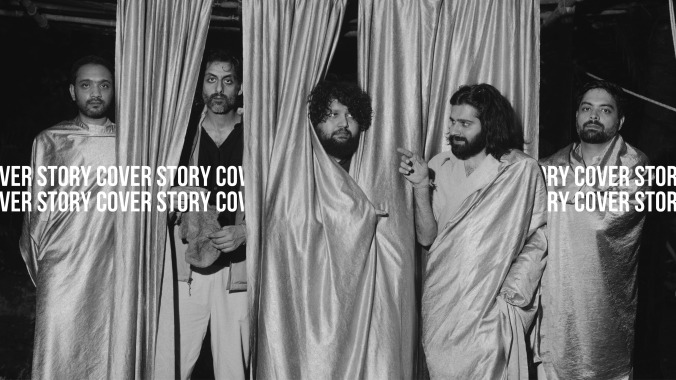

Peter Cat Recording Co. Have Been Waiting For You

Last year, the Delhi band sold out their inaugural North American tour. Now, they’ve returned with their first album in five years, the otherworldly, soulful, and cinematic BETA.

Photos by Tenzing Dakpa & Salihah Saadiq

On an amber-warm May evening in 2023, Peter Cat Recording Co. played their first-ever show in the dusty, shabby, too-dark A&R Bar—one of three venues stacked against each other on the outskirts of Columbus, Ohio’s Arena District. The quintet had been rollicking around Delhi for the better part of a decade now, but their arrival in the Arch City was rewarded with a sold-out crowd. Peter Cat Recording Co. had never toured in North America before, but that string of gigs was a celebratory end-cap to 10 years of lineup changes, high streaming numbers and two great records, Portrait of a Time: 2010-2016 and Bismillah. Peter Cat make transnational music with an extravagant, filled-out wardrobe. One moment, they sound like space-rock cadets; in a flash, they’re alternating between heady thumpers and rapturous jazz ballads. It’s thoroughly puzzling and unquestionably resplendent.

Suryakant Sawhney stood at the front of the A&R stage, draped in a lighting that barely contrasted the room’s low-tinted ambiance. His bandmates—Karan Singh, Dhruv Bhola, Rohit Gupta and Kartik Sundareshan Pillai—were more silhouette than discernible figures, as an atmospheric field recording crunched into a horn arrangement that serpentined into “Bebe de Vyah. The concert melted into itself. Sawhney rarely bantered with the crowd, preferring to let his soulful warble shepherd songs like “Floated By,” “Portrait of a Time” and the eight-minute Everest, “Memory Box,” instead. It was like watching a phenomenon untangle on stage. To step into the Peter Cat Recording Co. world is to buy into their multi-dimensional oeuvre—a catalog fit for marriage ceremonies and sea-shanty songbooks near and far.

Before Peter Cat Recording Co. hit the States last spring, they’d been working on some new demos—having recorded four or five tracks in spaces across Goa and in Gupta’s studio in Delhi. “We were just waiting for this body of work to finish,” Sawhney says. “I guess it seems to take us at least four years.” Bismillah came out in 2019, and it’s racked up over 40 million streams since. The 2023 tour was so fruitful and full of discipline that it inspired the group to, after finishing their final gig in Vancouver in June, rent out a studio in Joshua Tree and develop a foundation for what would become their third LP: BETA. Taking the stage every night invoked deadlines, which helped Peter Cat amp up their already-anomalous chemistry with each other. “[The tour] gave us a schedule to follow, which I think is great,” Sawhney adds. “I think it was a relief to get those songs out of our system. By the time the tour ended, we’d also played together for such a while—and we’d hardly done so many shows together—that we were a good, tight unit at the end.”

When the band returned to Delhi, the anecdotes they all shared with their friends and family centered around those Joshua Tree sessions, and BETA now exists as a living, breathing document of those days. Sawhney calls their North America shows “a weird little dream.” “It was hard to really ingest what had happened,” he says. “And the way we are, we aren’t necessarily the most vocal about our excitement as a group. We just sort of take it in.” Gupta quickly mentions that there was a shooting in Columbus the same day Peter Cat played at A&R Bar, near their Airbnb. “We did tell everybody back in India that America is very unsafe,” Sawhney quips. “Don’t go to Columbus.”

Peter Cat Recording Co. haven’t played any shows since returning from Joshua Tree last summer, though they are scheduled to return to America with Khruangbin this fall. In the past, before Bismillah and during the era that Portrait of a Time captures, they weren’t turning clubs inside out nightly. The industry in India didn’t have the infrastructure in place for any sort of routine gigging culture. And, at this point in the band’s career, having a mantra of “let’s play every day” isn’t in the cards either, nor does it have to be. “I think it would have been nice, 10 years ago, to have that many options,” Sawhney admits. “That’s how a band gets really tight, just playing again and again—not necessarily practicing together but playing together live would have been really instrumental in that.” The North American tour was the first time Peter Cat ever played their own catalog so consistently. After two-dozen shows and nearly two months on the road, their alchemy was tighter than ever. It only makes sense that, in the immediate wake of that journey, they went into album mode and made their best record yet.

Album mode is, according to Gupta, three or four-week-long “camps” where the five musicians stay in the same place and make music together. It’s not uncommon for bands these days to have their membership spread out in different places, and Peter Cat Recording Co. are no stranger to that either. Gupta lives in another city, and even Sawhney is often someplace outside of India. Peter Cat’s time spent together is often condensed and incremental, but it never takes long for them to snap back into focus. “Everybody’s getting busy with their own life, so it’s figuring out how to carve the time out in your life and make it happen,” Sawhney says. 10 years ago, the band lived on the same street, running snake cables through vents and from room-to-room. It was, as Sawhney calls it, a real “DIY-what-the-fuck-is-going-on?” setup. “There was a routine of showing up and jamming,” he continues. “It wasn’t necessarily a planned thing. We were younger, so we had nothing to do. This was our life. We’d show up happy.”

Despite having over 500,000 monthly listeners on Spotify, the origin story of Peter Cat Recording Co. isn’t so well-known. Search the band online and you’ll get a vague response about Sawhney having a “spiritual awakening” in San Francisco in 2008 that made him decide to pursue music as a career. He met Singh at IILM University in Gurgaon, but after a year of classes he wanted to “get out of the country and experience something else.” “I came home and me and my mom spent one afternoon thinking about it, and I looked at the map and it seemed like San Francisco was as far away from Gurgaon as possible,” he says. “I had always seen that city as something I was romantically attracted to. I can’t remember what it was, but it might have been [because of] Stark Trek. There was some poetry I enjoyed. I just felt drawn to it.” Sawhney applied to art colleges in the Bay Area, got in, spent three years on the West Coast and then dropped out before his first senior year semester.

I ask Sawhney about what that spiritual awakening was all those years ago. “I did mushrooms, basically,” he replies. “It sounds so funny when you actually say it out loud, but it really was something like that for me. Up until then, I had never considered music as even a career option or ever taken it seriously. But, I had a couple of friends [in San Francisco] and we all did mushrooms together for the first time. It felt like some sort of floodgate had opened for me.” Sawhney is honest about having what he calls an “ego death,” and that something centrally shifted within him—but it wasn’t like that two-day, “everything is so beautiful, I understand everything now” afterglow that most people associate with psilocybin trips. “I did suddenly have clarity within myself,” Sawhney continues. “It was about inhibition and believing in whatever my mind was cooking up.”

In 2020, after Bismillah, the band moved into the same house together in Goa so the workflow could develop into something stronger and faster. Four out of five members holed up there for about three years, and Bhola and Gupta still live there. The band eventually rented out a small cottage in Goa. It was an old, abandoned place run by a priest who gave them permission to record there in the middle of the night. “We had mics in different rooms, in this empty-ass house, and it just sounded beautiful,” Sawhney says. Out of those sessions came “Flowers R. Blooming,” the seven-minute tidal wave of sitar, distorted vocals, electrostatic and a chugging tapestry of saxophone that is now regarded as the origin of BETA. “You always need something to hook onto and then build around, to see where it can go,” Sawhney continues. “That just felt like the correct starting point. There were songs made prior to that, but they didn’t feel like good launch points. [‘Flowers R. Blooming’] felt like it was cooked when we were finished.”

A lot of Peter Cat Recording Co.’s music is producer-driven. There is a songwriting process and a performing element, but so much of the band’s magic happens in the mixing and mastering phases. “A lot of it is sitting in a studio and figuring out how to engineer the song, in a hip-hop or electronic music sort of way,” Sawhney says. “Flowers R. Blooming” was an instance where everything happened live, and it was the track that gave Sawhney the motivation to want to go through with finishing BETA. “Suddenly” was just as consequential, as the band rented out a furniture showroom owned by one of their friends and set up a recording studio in it for a weekend. “It’s like playing in an IKEA,” Sawhney continues, laughing. “Our recordings depend on that sort of ambiance—something giving us that inspiration and capturing that space in a recording, as opposed to just a studio, which seems kind of stale. When those pieces start coming together, you start seeing the possibility of an album. And still, it’s difficult.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-