Overpriced Dark Side of the Moon Boxed Set Is A Mixed Blessing

Bound to frustrate loyal fans, the umpteenth reissue of Pink Floyd’s towering classic nevertheless gives us an excuse to revisit a first-rate live recording.

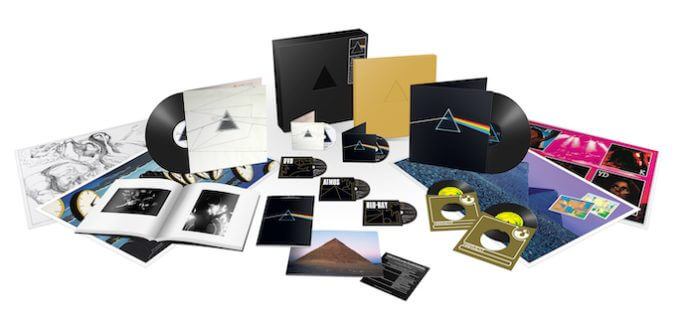

What else is left to say about Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon at this point? Judging from the 50th-anniversary edition, the resounding answer is: nothing. Though the new, lavish package isn’t exactly short on features, it contains no retrospective commentary whatsoever—a highly unusual move when it comes to milestone reissues, especially of albums as recognizable as this one. If surviving members David Gilmour, Nick Mason and their estranged former leader Roger Waters are sending a message with this presentation, it’s that the music here speaks for itself.

Of course, it could just be that the two camps, locked in an eternal feud since well before Waters left the band in 1984, simply couldn’t agree. (A difference of opinion over the liner notes for last year’s deluxe Animals reissue delayed its release for months.) Either way, the absence of an imposing outside narrative only perpetuates the sense of mystery that’s fundamental to these songs. And it’s not like the public needs much help putting this album into context: a game-changer that towers over the pop-culture landscape on-par with Led Zeppelin IV, Sgt Pepper’s and Thriller, it’s hard to imagine that anyone with even a rudimentary knowledge of pop culture doesn’t recognize the iconic cover image, at least in passing.

Dark Side is not only one of the best-selling albums in history, but it also spent an astoundingly long stretch of time on the Billboard 200. The tallying method for that chart has changed multiple times since the album’s release in March of 1973, but let’s just say there’s a prevailing sense that this music has been around so long it feels like it’s going to live on forever. Looking back half a century later, it’s hard to put one’s finger on why Pink Floyd struck such a profound, seemingly universal chord with their eighth full-length.

A deeply insular outfit who eschewed the sweaty throes of rocking-out for an almost unnatural level of restraint, Pink Floyd came across as utterly disinterested in making a connection with the audience, or even in highlighting themselves. Watching the band burn its way through earlier—and considerably more ferocious—material the year before making Dark Side in the classic concert film Live at Pompeii, other than drummer Nick Mason, the rest of the band barely moves, even as the music approaches a boil. Fittingly, there’s no audience, and the band appears puny before its surroundings, the amplifier cabinets and the power of the music the only defense against getting swallowed up.

While Pink Floyd were not performers in the classic sense, they didn’t lack passion. In fact, it was their ability to marshal their collective energies into a kind of musically tantric steadiness that put them in a class entirely by themselves. With Dark Side, they hit the bullseye, softening their approach while sharpening their focus and broadening their scope, creating a work of unparalleled flow and atmosphere. The acid-fried psychedelia of their previous work may have marked Pink Floyd as unlikely candidates for mass appeal, but there’s no questioning why repeated generations of listeners have gotten whisked away into their own heads while listening on headphones.

One of rock music’s ultimate start-to-finish statements, Dark Side set the high water mark for the concept album, as well as for headphone listening. One could literally speak volumes about the appeal of every instrument, every note, and every intangible quality on this record: Gilmour’s lighter-than-air guitar (and vocals to match), Richard Wright’s jazzy piano chords, the mutant earworm funk of Waters’ bass, Mason’s ability to hit the drums as lightly and as unhurriedly as humanly possible, the background vocals and saxophone from guest musicians whose parts fit seamlessly, the one-of-a-kind production from Alan Parsons and Chris Thomas—and, of course, Waters’ overarching lyrical concept, which points inward while looking outward at universal themes.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-