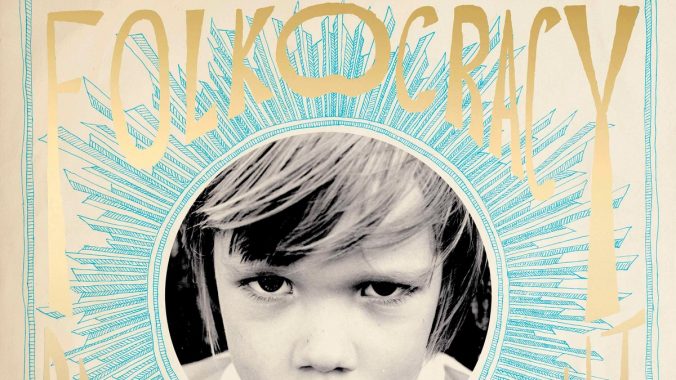

Rufus Wainwright’s Folkocracy is a Sweet and Simple Self-Reflection

Rufus Wainwright is, at heart, a performer. It’s as easy to imagine the king of 2000s baroque pop on a Broadway stage as it is to picture him plucking at an old guitar on a creaky New England porch. In Folkocracy, his eleventh studio album, Wainwright marries those two versions of himself using a mix-’n’-match variety of folk songs with the help of a bevy of family, friends and fellow musicians. The collaborations range from off-kilter takes on 19th-century sea shanties to bright, triumphant celebrations of Neil Young and The Mamas and the Papas.

The work is Wainwright’s 50th birthday gift to himself, and it reads as such. It’s the pure definition of a “passion project,” unlikely to achieve massive commercial success or push very hard at the musical outlines one might draw around Wainwright at this point in his career. Folkocracy is, for the most part, soft and sweet—a tribute album to his complicated upbringing under folk legend Loudon Wainwright III. Its composition is clearly thoughtful, its delicate marginal touches carefully conceived with the help of producer Mitchell Froom.

Wainwright is serious about the notion of the “folkocracy” itself, music that belongs to and circulates amongst the volk, or the people. The collaborative emphasis is clear, both in the sometimes-snazzy, sometimes-familial features that decorate 12 of the record’s 15 songs and in the intensely permeating dual nostalgia of folk as a genre and as a fixture in Wainwright’s boyhood. “I’m from a bona fide folkocracy,” he explains in an online bio. “As I hurtle towards 50, I’m back where it all began.”

Folkocracy is a paternal whisper rather than a youthful bang. At times, it borders on kitschy: If, for some reason, you were looking for an operatic rendition of “Shenandoah,” you’re in the right place. Nevertheless, Wainwright’s artistry is not lost amidst the folds of old-timey war songs and love ballads. His trademark theatrical vibrato and liquidy lilt mark the tunes as his own—minus his coverage of a few questionable ditties.

“Twelve-Thirty” is the closest we get to a dancey number on this album, a mercifully bouncy take on The Mamas and the Papas after the near-painful seriousness of the album’s openers. It brings to light the happier side of Wainwright’s shameless (and shamelessly enjoyable) theatricality, and his voice intertwines beautifully with Sheryl Crow’s signature belt and Susanna Hoffs’s girlish twang. “Down in the Willow Garden,” featuring Brandi Carlile, is a similar success. Perhaps Wainwright belongs with the queens of country. The marriage of Carlile’s moody drawl and Wainwright’s operatic vibrato creates a vintage, Rosanne Cash-esque bent to the piece. It’s emotionally naked and unabashedly earnest, the linchpins of Wainwright’s corpus.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-