How 2014 Was the Worst Year in Pop Music of the Last Decade

2014 had hits that weren’t just bad—they were nameless, unidentifiable and unimpactful. It was a year without an identity.

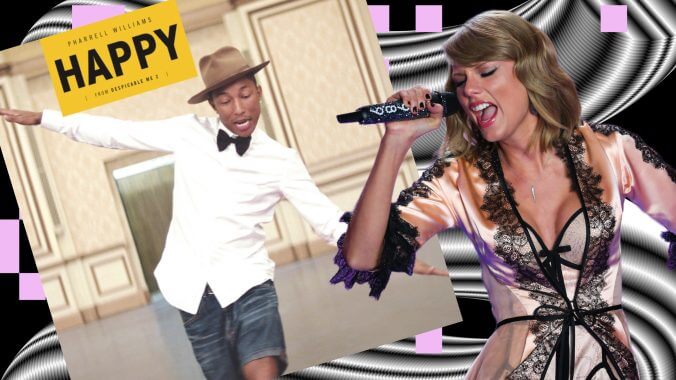

Photo by FashionStock.com/Shutterstock

10 years ago this month, Pharrell Williams’s single “Happy” reached number one on Billboard’s Hot 100 chart and remained there for 10 consecutive weeks. Bolstered by its success as a soundtrack single for Despicable Me 2 and colossal radio favor, “Happy” became the best-selling song of 2014 by nearly 2 million sales. But there’s something despicable—pun intended—about “Happy” and its tremendous success. In the late 1990s and 2000s, Pharrell (along with childhood friend Chad Hugo) built a reputation as one-half of the production duo the Neptunes. His and Hugo’s productions were boisterous and playful, and their work with Kanye West, Jay-Z, Clipse, Kelis, Snoop Dogg and a platinum guest list of other artists defined the 2000s. When Pharrell collaborated with pop stars like with Justin Timberlake on “Rock Your Body” or Britney Spears on “I’m a Slave 4 U,” his touch was fresh and lively. Pharrell Williams was, in short, cool. Anyone looking through Pharrell’s production credits would suggest he’s more than capable of creating a global smash under his own name. No one could have guessed it would be as boring as “Happy.”

Pharrell is not the only artist who would be ubiquitous in the worst way in 2014. A cursory glance at 2014’s Billboard’s Year-End Hot 100—which tracks the best-charting songs of the year on Billboard’s Hot 100 through the year—reveals some of the most regrettable hits of the 2010s. There are ultra-saccharine ballads like John Legend’s “All Of Me,” A Great Big World and Christina Aguilera’s “Say Something,” Passenger’s “Let Her Go”; corny “alt” anthems like Bastille’s “Pompeii,” Imagine Dragons’ “Demons” or American Authors’s “Best Day Of My Life”; trite pastiches, like Meghan Trainor’s “All About That Bass” and MAGIC!’s “Rude.”

Bad hits are a part of life, and as reliable as our planet orbiting the sun. Every year offers its own songs that age like milk. But, from a purely commercial level, 2014 had hits that weren’t just bad—they were nameless, unidentifiable and unimpactful. This was a year without an identity. Sure, 2013’s Billboard Year-End chart includes plenty of songs that also don’t stand the test of time (the Top 10 of that list includes not one, but two tracks by Macklemore and Ryan Lewis). But, at the very least, there was a defining characteristic to pop music culture that year: the cheap, blown-out EDM of Baauer’s “Harlem Shake,” Rihanna’s “Diamonds” and Pitbull’s “Feel The Moment”; or the mid-tempo empowerment ballads of the Obama era, like P!nk’s “Just Give Me A Reason” and Katy Perry’s “Roar.” From Sia to Skrillex, pop music from 2010 to 2013 tended towards ear-consuming bombast. If nothing else, this first era of the 2010s had personality and persona. Where did that go?

Of course, there is an un-ignorable and obvious exception. Who else could it be but Taylor Swift? In October 2014, Swift released her fifth album and first “official pop” album, 1989. According to the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI), 1989 was the second-best selling album of the year—bowing out only to the soundtrack to Frozen. But even 1989 seems to enforce this theory, due to how Swift’s pop persona was, by her design, ambiguous and general. She made an album that was defined by its anonymity, and her writing could still connect to millions of listeners on a personal level. But the album—and particularly lead single “Shake It Off”—could also soundtrack workout classes, fifth grade PTA events and endless radio playlists. And not to split hairs, but 1989’s superior singles “Blank Space” and “Style” were both more popular in 2015.

Making broad-stroked arguments about a year of music is a futile exercise. Like every other year, 2014 had plenty of enduring albums, in pop music and otherwise—like FKA twigs’ LP1, Run the Jewels 2, Mac DeMarco’s Salad Days and Lana Del Rey’s Ultraviolence. At the same time, 2014 lacked a pervading identity or direction—yielding a lot of forgettable albums and hits that do not stand against the test of time. It had the lowest total revenue of recorded music since the year 1989, coincidentally, and it saw structural changes in how music was marketed and consumed. The result is a pop music void, where the best-selling music was traditional, boring and, to quote Pharrell, “Happy.” Ultimately, the way that artists, labels and listeners chose to fill that void portends the structures, and many problems, that the music industry faces today.

In 2014, Spotify’s dominance of music culture began in earnest. After launching in the U.S. in July 2011, the streaming service stagnated through the early 2010s. But by 2014, streaming’s implications for the music industry finally emerged: Between the end of 2013 and the end of 2014, twice as many people were googling Spotify, according to Google Trends, and subscribers for the streamer exploded. The Los Angeles Times reported that Spotify ended 2013 with 24 million active subscribers. By January 2015, that number had more than doubled to 60 million active users.

Inversely, digital downloads decreased. Digital downloads—namely buying a song or an album on iTunes—accounted for 40% of the recorded music industry’s revenues in 2012 and 2013. By the end of 2014, that fell to 37%. And, as expected based on its exploding subscriber count, revenue from streaming increased from 21% in 2013 to 27% in 2014. By 2015, streaming accounted for a larger share of the industry’s revenue than digital downloads.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-