The Everlasting Influence of Jerry Garcia and the Grateful Dead

The Dead continue to inspire musicians keeping the songs alive through tribute bands, festivals and dearly-held memories nearly 30 years after Garcia’s death.

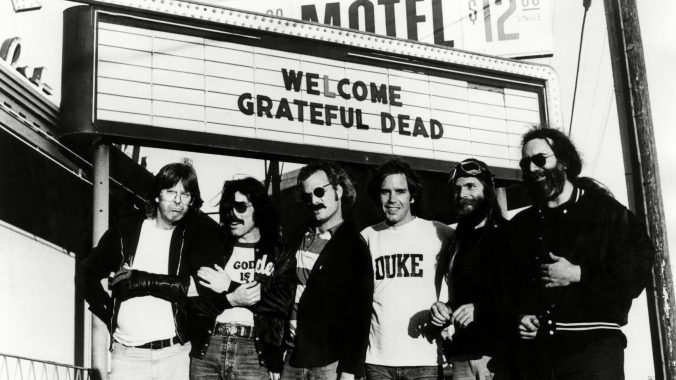

Photo by Everett/Shutterstock

“I remember the sound of his laugh and the mixture of smoke and whatever aftershave,” says Sam Grisman, recalling Jerry Garcia in his living room. “He was the only one my parents would let smoke cigarettes in our house.” The Sam Grisman Project, a band inaugurated in 2022—with Sam on upright bass—revives the music of Garcia and venerable bluegrass player David Grisman, or “Dawg,” Sam’s father. Snug acoustic tracks on the likes of Jerry Garcia/David Grisman and The Pizza Tapes were recorded in the Grisman home studio in Mill Valley, California, the former released in the early 1990s. The two had met in the 1960s as fellow travelers. Later, David would appear on the Grateful Dead album American Beauty, adding mandolin to shimmering perennials “Friend of the Devil” and “Ripple.” “I want to offer something to folks that would remind them of the music my dad and Jerry made together,” Sam continues.

The Grateful Dead formed in 1965 and the rest is legendary, offering a mode of fandom not far from vocation. Like so many obsessions of the soul, it’s guided by a mysterious private power. An example? The weird, warm heartache which arrived when a show began, because you knew it would end. The setlist changed every night, each version of a song novel from its last. Interpreting the music of the Dead and its members—two guitars, two drum kits, bass, piano and vocals—remains an ongoing pursuit. While founding members continue to tour in impressive iterations, there’s also many other musicians keeping a long, strange flame alive in their own style. There’s Joe Russo’s Almost Dead. There’s Grateful Shred and Mars Hotel. There’s a group in Brooklyn infusing Dead themes with disco stylings. There’s one from Denver doing mash-ups with Steely Dan songs. Basketball great and tie-dye virtuoso Bill Walton has appeared as a percussionist in the Electric Waste Band out of San Diego. There’s an annual Skull & Roses festival on the Ventura County Fairgrounds, off Highway 101.

When Melvin Seals first entered the warehouse where the Dead rehearsed, he didn’t know what to make of it. “There’s backdrops of skeletons all over the place, I was a little scared of these people,” he says. He’d first played the organ in church, then in a Broadway production, then with blues rocker Elvin Bishop of “Fooled Around and Fell in Love” fame. There was a night on tour where his path crossed with Garcia’s and, in 1980, Seals joined the Jerry Garcia Band and its dreamy mix of rock, soul and springy renditions of songs like Smokey Robinson’s “I Second that Emotion” and Bob Dylan’s “Tangled Up in Blue.”

Garcia deemed Seals the “master of the universe.” “I didn’t know what that meant,” Seals laughs. Possibly: placing each element where it belongs, the star-crossed ballads and romps alike. He vocalizes the opening of “The Harder They Come,” the Jimmy Cliff classic punctuating Garcia Band sets. “I didn’t understand how it could be so loose,” he says. He’d been accustomed to a certain precision. “I had to learn it wasn’t about how tight it was. It was the heart, the soul. It was something else Deadheads felt from the music they liked,” he continues. “What leaves the heart reaches the heart. Maybe we made all kinds of mistakes, but there was a heartfelt thing they loved.” Seals says Dead-tinged music is a calling. “It’s still growing. They’re the only band I know that has cover bands all over the world.”

Sam Grisman began playing by age four. “‘Bass’ was actually my first word,” he says. He explains it’s a bluegrass counterpart to mandolin, that his strings-wielding father might have hoped he’d gravitate to it for that reason. They’d practice songs with only one chord change, simple but not. “My dad was trying to emphasize playing in time,” Sam says. “He knew I wouldn’t be able to make the steps beyond if I didn’t secure rhythm from the inception.”

Cut south of the Finger Lakes, Sam Grisman Project’s LP Temple Cabin Sessions Volume 1 jumps with empathic exchange. The group is Grisman, Ric Robertson, Chris “Hollywood” English and Aaron Lipp. Grisman and Robertson first met as teenagers and, in 2023, the band visited about 24 states. 2024 continues apace. “We’ve been touring in our personal vehicles,” says Grisman. “It’s what we’ve been able to afford.” He drives a Subaru Ascent with over 122,000 miles on it. “It feels like these songs need to be played and it feels like people need to hear them.” Some in the audience are familiar with the catalog of Garcia and Grisman or the Dead, some aren’t. “Our approach is centered around the musical ethos of my dad and Jerry, which was about diving into the material they felt like exploring with their own voices,” he continues. “We just have to love the tune. That’s the only rule.”

Joni Bottari is lead guitarist in Brown Eyed Women, an all-women ensemble from multiple states and a reference to the sun-bursting Dead song introduced on the Europe ‘72 album. “My first Grateful Dead show was the Beacon Theater in 1976,” Bottari shares, noting that she would have been about 15 years old at the time. “They’d been playing arenas but now they were playing theaters. It was complete mayhem. I walked in and my mind was completely blown.” She grew up on the Jersey Shore as the youngest in the family. Her older brother was in a band that split a bill with Springsteen. Workingman’s Dead hit shelves in June 1970 and he brought it home, American Beauty soon after. “At the same time I was learning to play the guitar,” Bottari continues. “I became obsessed, especially ‘Box of Rain.’”

In middle school Joni joined her first band, playing eighth grade dances. In the early 1980s she joined a band called Spellbound, playing in Manhattan at CBGB. But then she suffered stage fright. “I never thought I would play again,” she says. “It was paralyzing.” She didn’t play live again for north of 20 years, but has since performed in several stage bands specializing in the music of the Dead. “Unless you get it, you don’t get it. But once you get it, it becomes part of your DNA.”

Workingman’s Dead also spoke to Rob Barraco, representing a roots rock entry in the Grateful Dead story following psychedelic blowouts like Aoxomoxa. “I’m sitting at an atmospheric river by a hotel in Menlo Park,” he says, on the road with Dark Star Orchestra, the journeying outfit of a quarter century dipping into Dead eras. A keyboardist from Long Island sporting a trademark bandana, Barraco appears to pull chords out of the wind. “The crazy thing about it, and what I like the most, is how much it takes to do what we do in a tiny amount of time. It can be maddening to wait all day to play three hours of music.” For Barraco, it was the final track off Workingman’s Dead that hooked him first, “Casey Jones.” His first Dead show was March 28, 1972 at Academy of Music in New York. “Being turned onto a kind of music I didn’t know existed was a beautiful thing,” he continues. Then he saw many shows in 1973, 1974—improvisatory concert design departing from the studio: “I knew in my heart, that’s what I wanted to do. You can abandon all your fears and be in the moment.”

“A lot of it is very hard to execute,” says Nashville songwriter Melody Walker, a member of BERTHA, an all-in-drag Grateful Dead project formed in 2023 in the wake of anti-drag legislation proposed in Tennessee. “But perfection isn’t the point,” Walker continues. “There is so much more to music than playing the right notes.” “By the time I started listening in high school, the Dead’s music felt like something I was finally ‘allowed’ to listen to,” adds BERTHA guitarist Mike Wheeler. “It was freeing, rebellious in its own wholesome way, and suddenly I felt like I was part of a community I’d long been intrigued by.”

Jerry died in August 1995. Clinton was president, Forrest Gump won Best Picture and Michael Jordan came out of retirement and returned to the Chicago Bulls. “They were actually planning a tour where they were going to play Red Rocks and maybe the East Coast,” Grisman says of his father and Jerry. “I think the only gig they played on the East Coast was on Letterman.” He explains that, as a toddler, he accompanied his family to most of the acoustic shows. “But I had no concept that Jerry was an icon,” Grisman continues. “That was my first time dealing with mortality. I assumed when somebody died, it’s on the news. I had no concept of how much he meant to our community.” Garcia’s death triggered an outpouring of attention and that twang of grief appearing to those whose favorite artists have reached them. “I started kindergarten and every teacher I had offered their condolences,” Grisman explains.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-