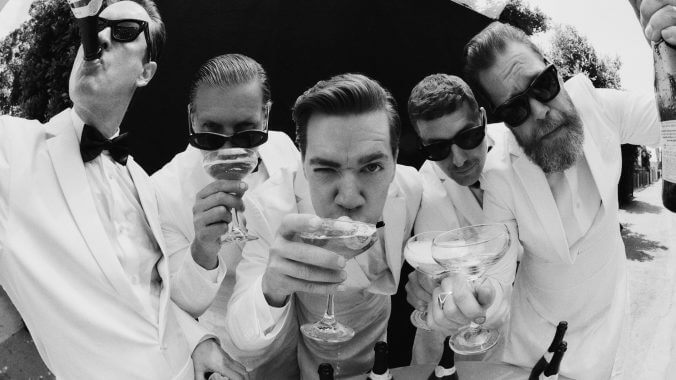

If you’re a fan of rock music, then you’re certainly a fan of The Hives, a Swedish quintet that’s been making heavy garage tunes for 30 years now. Beginning in 1993, Howlin’ Pelle Almqvist, Nicholaus Arson, Vigilante Carlstroem, Chris Dangerous and Dr. Matt Destruction have created a brand within their band. After The Johan and Only replaced Destruction in 2013, the lineup has remained solid since. In the three decades since forming, the Hives have established themselves as one of the best live acts in the world—with Pelle at the center of it all, forever running laps around everyone else and holding the title of being one of the globe’s fiercest frontmen.

Despite touring pretty consistently over the last decade, the Hives haven’t made a record together since 2012, when they released Lex Hives to much fanfare. The announcement of their most recent endeavor, The Death of Randy Fitzsimmons, was treated like a long-awaited comeback for the five musicians—and the album’s three lead singles signaled a proper turn towards permanent immortality for a band that first kicked up dust on their 1997 debut album Barely Legal and has long awaited their flowers.

Known for being those loud, shredding dudes in black and white suits who make chaotic, unmistakable garage rock classics, the Hives found themselves in a state of flux after their longtime songwriter, Randy Fitzsimmons, passed away in the time that’s passed since Lex Hives. When they stumbled upon Fitzsimmons’ grave, they found demos for the 12 tracks that now make up The Death of Randy Fitzsimmons. Whether or not they can continue without their beloved, secret sixth member beyond this record remains to be seen, but there’s no doubt it’s going to be one hell of a ride.

PM: You’re right, well, one of my best friends lives in Sweden, and she was telling me that there’s some lore there about the Hives. She told me that everyone is under the impression that you guys come home to record and crash at your parents’ houses during the sessions. Is there any truth to that legend?

PA: Crash at our parents’ houses or crash our parents’ houses? Destroy them or sleep over?

PM: Both…maybe?

PA: When we rehearse, I stay at my parents’, and a lot of other guys did, too—because we don’t live in that city anymore, or town or village or whatever. The only person who lives in Fagersta now is Nicholaus [Arson]. We have a space there. If you’ve seen a Metallica documentary, where there’s a warehouse with a bunch of road cases in it, we got one of them there. It’s an old, defunct shirt factory that we go to. We make records in rehearsal, really. The recording is pretty fast, but the rehearsal takes a long time for us. But it’s true, I stay in my parents’ basement. I’ve yet to destroy the house, though. I guess I did that when I was a kid, I once threw Nicholaus into the wall and the plaster busted. There’s a Nicholaus-shaped hole in the wall in the basement that’s still there—so, I guess, there was some crashing of the other type going on. But that was when we were forming the band, trying to agress on music—which is still the challenge.

PM: I’m not sure if that ever stops becoming a challenge.

PA: It doesn’t seem like it. I don’t know any adult bands that agree on anything, so I assume it’s part of the thing. Trying to work with people who have 50,000 people cheering them on at the show, I think it will always be difficult—because everybody [in the band] assumes it’s because of them and they think they do everything right. And then you start arguing.

PM: Whether it’s adopting different nicknames across your career, turning out in matching suits, or formulating an entire album around an imaginary sixth member, the Hives have often been at the forefront of theatricality in rock ’n’ roll without any of the tongue-in-cheek stuff that a band like KISS tries to pull of. At what point did it become obvious that bringing a fictitious layer to the band was something you not only could do, but you could do it well for almost 30 years?

PA: When we formed, it was a big thing—being mundane in rock ‘n’ roll. We always thought that was bullshit, whether it was Guided By Voices or that scene, where you wear the same clothes. You’re nothing special, you’re like one of the crowd but you’re playing music. I guess they were reacting against something and feeling like what they did was rebellious, but, when we came out, we felt like that was what we should rebel against—the thought of “every man rock.” So, I think it was pretty immediate. We didn’t think our lives were outlandish and interesting enough. Sweden is such a safe, Socialist country where everyone’s doing good—which was awesome to grow up in, it was great. You didn’t know if your friends were rich or poor, you really had no idea. There was no difference, and I think that was very good. But we wanted the band we created to be more special than that. It’s showbiz, it’s all bullshit. It’s just that a lot of band’s bullshit looks closer to reality. We never had that problem.

PM: Obviously the US and the UK were sending their own troops into the garage rock revival around that time. What were the resources in Sweden like when you and the guys were just starting to get your bearings as a band in ‘94 or ‘95?

PA: In the UK and the US, when those bands broke through, we’d already been around for, like, seven years. We predated the White Stripes and the Strokes by a couple of years. But, the resources were you could afford to buy one album a month, maybe. You had to make it count. And you’d go to the record store in the big city and pick something that looked like it was a good record. We knew what we wanted music to be, but it was hard to find. It was a lot of discovery. We could afford to buy one new rock ‘n’ roll or punk rock album a month, so we listened to that. And then, it was gas station compilations of hits of the ‘60s and hits of the ‘50s that we’d steal stuff off of. We rehearsed next to a disco and we would steal riffs or disco bass lines that we could hear through the wall.

PM: How many bands were around that you were able to look up to and pull influence from?

PA: We played with, mostly, hardcore punk bands or indie pop bands. There were no garage rock shows, really, so we would have to play with anything else that seemed like alternative, garage music. It’d be us and a death metal band or us and a punk band. And it’d be awesome. We were kind of in the punk scene, but we didn’t really feel like we were doing what they were doing. And in the punk scene, it was very ill-received, us wearing suits and all that. But we also got a big kick out of that. We were rebelling against the rebels.

There was a record company in our hometown that put up shows, and it was pretty spectacular. The amount of hard, underground music—which was mostly metal and hardcore punk—that would play in our hometowns, American and UK bands would come and play in our 12,000-people, shithole town, real international royalty of punk and metal. We got to go to energetic shows when we were children. I think that really made it seem possible. If these Brazilians can play a metal show in Sweden, we could probably go play a rock ‘n’ roll show in Brazil. I think that was really important for us to feel like stuff was possible. So, it wasn’t that bad. Actually, it was pretty good. It wasn’t what we were doing, but we could weasel our way in there. “Hey, you guys have got a metal band. Can we play a show with you?” We’d have varying success with the metal people. Some of them hated us, some of them thought it was cool.

PM: Sometimes you’ve gotta wedge yourself into wherever there’s room.

PA: We played a school disco, too, and that was the same reaction: half-disgust, half-excitement. That’s always what we were used to. We’d play anywhere, and there was, maybe, three venues in our town and I think we might have played 50. We rented a scout cabin, played in an empty mall—stuff like that.

PM: Much of what makes the Hives so legendary is the live show factor. I know some artists are more keen on writing and recording and then figuring how to fit the tracks into the puzzle of a stage performance later, while other acts are hyper-aware of how a song might be performed in front of an audience before the lyrics hit the notepad. Where do the Hives land on that spectrum? What’s the relationship between recording and performing?

PA: Well, we know that we’re gonna have to figure it out sooner or later. For what I think of rock ‘n’ roll, it is the same thing—if you make it too elaborate or you can’t reproduce your studio thing on stage. It used to be that we’d play all of the songs live a lot before recording them, and that was really helpful in figuring out what worked and what didn’t work. It’s not fun to do anymore, because there’s a bunch of different versions of five songs uploaded [to YouTube]. But I think, for us, if it works on the album, it’ll work live. And some of them work better than others. Some of them work better on an album and some of them are worse live, and vice-versa.

But, we’re just gonna have to make the music we want to make and then be confident that it’s gonna work. We’re not thinking, in the studio, about how to make it work. We just assume that it will, because it’s about energy. You have to keep the energy going all the way through the song. That’s the way to make it exciting on stage and on the album. If it excites you all the way through on the album, chances are it’s going to work pretty well at the show.

PM: I caught that recent video where you got clocked in the head by your own mic while playing, but you kept going with the blood dripping down your face. When you’re in that moment, is the adrenaline just so off the charts that everything beyond the music becomes so circumstantial?

PA: Pretty much, yeah. I was annoyed for like a second that I might have to stop and get stitches. I was like, “That’s gonna fuck up the show and also fuck up the stage outfit, and I only had one of that set.” Blood is dripping on it and I’m like, “I hope it drips on mostly the black parts, because then you’re not going to see it.” I’m not thinking about my own health or safety, reall. I’m too wired for that. And, also, it’s a challenge. If my head starts bleeding and people see that I don’t react, they understand that this is a force beyond human control. I was almost happy that it happened, you know? I was telling the other guys that they should bleed more.

PM: Alice Cooper once told me that he’d rather retire than half-ass a show.

PA: You’re proving you’re a wuss, and the audience can tell. The crowd is whatever the crowd is, they’re gonna react however they want to react and you’re gonna do whatever you’re gonna do. They don’t owe you anything and you don’t owe them anything. But, in order to impress them, you’ve got to be impressive. You can’t let anything stop you.

PM: At what point did it become clear that the next chapter of the Hives was going to be an homage to Randy Fitzsimmons and his lifelong impact on the band?

PA: Well, when he disappeared, we couldn’t finish an album. We didn’t have enough music. I’m gonna assume it’s a fake death, because that feels better to me. But, at that point, it’s also been such a long time. 11 years since the last album, that feels insane. It almost seems not worth mentioning. [The Death of Randy Fitzsimmons] being the title, it was very late. It was, like, a year before the record came out—and the record hasn’t even come out yet, so it’s like a year ago?

PM: If it turns out that Randy did fake his own death and he returns, what’s the first thing you’re asking him when he comes back?

PA: I’m gonna fucking punch him in the face. Maybe I’ll kill him!

PM: Then he can have his real death.

PA: Right.

PM: SPIN once called his songwriting credits a ruse, but now that he’s passed and disappeared and his legacy is felt on this new record, what would say to the doubters about how his influence has nurtured and guided the Hives’ destiny?

PA: I’m not that interested in the doubt thing. Because, I’m saying he exists, you’re saying he doesn’t exist and you’re saying your proof that he doesn’t exist is that we’re collecting the money. If you were actually trying to be a secret songwriter, wouldn’t that be the first thing you sorted out, so you’re not on any kind of address sheet for picking up the money? I’m saying he exists, SPIN Magazine is saying he doesn’t exist. Who knows better, me or them? I don’t really think about the doubting at all. “Well, he exists. No, he doesn’t.” We’re not getting anywhere are we? I’ve had this conversation for, like, 25 years and there are no new angles to it that I know of.

[Randy] has been really important to us, because we couldn’t have done that ourselves. Obviously, he couldn’t have done it with a different band, I don’t think. It’s a mutual thing, a symbiotic relationship. I don’t know if we can do it without him. We’ll have to see what the future holds.

PM: The Hives have always been the suit kings of rock ‘n’ roll, but I have to ask—because you guys have been wearing suits on-stage for years—what’s the worst suit you’ve ever seen?

PA: There’s plenty of fucking terrible stage outfits, I think, especially in stadium rock. I think people think that you’ve got to be really colorful, so that you stand out. I mean, most big stadium rock outfits look ridiculous to me. I don’t want to point out a certain person or certain stage outfit. Most of it’s terrible. It’s like the worst TV show you’ve ever seen, when it’s so bad that it’s usually entertaining. It goes full circle and gets good.

PM: That old saying, “it’s so bad that it’s good.”

PA: Yeah, exactly. I’m into that. It could be argued that there was a Mick Jagger thing in, like, 1982, where he wore an aerobics outfit, like a leotard and knee pads and stuff. But, since it’s Mick Jagger, it’s almost better than him wearing something that makes sense. It defeats any kind of good outfit, because it’s Mick Jagger. But that on the dude from Coldplay, it wouldn’t work.

Our producer, Patrik [Berger], once recorded a legendary funk bass player who was on platforms and flares and wore a big hat. He looked like a blaxploitation movie star. Patrik asked him about his clothes, and he said “Well, you know, to me, cool is comfortable.” And I buy that 1,000%. I would not feel comfortable wearing sweatpants on stage at this point. I also think the first rule of fashion is you have got to be, at least, a little bit uncomfortable. We’re playing Rome this week and there’s a heatwave called Cerberus and it’s going to be 48-degrees Celsius. Wearing suits, it’s fucking terrible. We played Coachella in top hat and tails and it was ridiculous. But it’s also like that bleeding thing. If we make no concessions to circumstances, that’s our way of showing that we have superpowers.

PM: It’s been 11 years since the last Hives album, but you guys were touring for a while after that. At what point does the touring routine become exhausted and the motivation to get in the studio and make another album starts kicking up a notch?

PA: Well, like eight years ago. But it just hasn’t worked. It’s pretty intense, touring for a year or two after you put out a record. We play all the fucking time everywhere, two laps around the world. And then we take it down to a week here and there, summer shows and festivals on the weekend. We did that type of touring for many years, which is not exhausting at all. But it has felt weird to not have new songs to play. It’s not a good feeling. I don’t think I would do that again. If I knew there was going to be 10 years, I think I wouldn’t have. If we’re gonna tour now, we’re gonna put music out. That’s my take on it.

PM: I think about bands like AC/DC or Def Leppard, and how they’re able to tour for the rest of their life without making a new album, or at least without making a new album that makes any reasonable headway in their catalog. And I then think about how many bands from Y2K are going to be able to achieve that same enduring relevance.

PA: The Rolling Stones and AC/DC, we toured with both of them and they play one song, maybe, from the new album and then it’s all old stuff. We’re not there yet. We feel like we’ve got to play at least half of the new album when we tour a new album. It’s also fun. I think the secret to rock ‘n’ roll is—an electronic musician from Norway told me this, and I think he’s right—you just need to stick together, just be a band for a very long time. And, at the end, you’ll just be the last standing from your age group or your genre. I guess, at that point, that seems like it’s almost the goal for us. All we’ve got to do is not quit, keep playing shows and not suck.

PM: You’ve mentioned in the past that becoming a stadium band is not something that you want to do. What’s the best version of that future now? What’s a good alternative that doesn’t include the novelty of recycling hits over and over on a big stage where people are paying $200 to watch you on a jumbotron?

PA: It’s not as fun. We’re doing a stadium tour now with the Arctic Monkeys. We’re playing in Milan, Rome and Athens. It’s like 90,000 people in football stadiums. I could get used to that, but I think the best shows are in places—I used to think it was 2,000 [capacity], but now I think, maybe, 2,000 to 6,000. That’s my favorite capacity to play. But, if we’re more popular, I’ll play to more people. I think it’s a weird, snobby thing to play to too few people. It just means that the tickets get more expensive. I’ll play to as many people that want to see us. If we were as popular as the Arctic Monkeys, I’m sure we’d be doing stadiums.

PM: The Hives put out their first record in 1997, before the pop charts dipped back in favor of rock ’n’ roll in the early 2000s. When you were making these rock records at the same time as bands like the Strokes and the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, did it feel like the buzz around rock music at that time was organic, or were bands getting lumped together by the press for the sake of trying to find something like the grunge era in Seattle?

PA: I think both. We got popular on our own without press. The Strokes already had a big record label when they started out, but the White Stripes and us released on some really small record labels at first, got attention from fans and then we got attention from the press after that. We played for a lot of people before we had any kind of mainstream press. All the interviews we did in the beginning were for little fan zines that xeroxed and stapled together. It took a while before the press caught on, but when it had reached the critical masses, you could definitely tell that people started looking for new rock ‘n’ roll bands to lump in with the scene. And a lot of them started because of that.

I think that, once that has happened, it starts to help itself. It becomes a snowball effect. If the press says there’s a rock ‘n’ roll revolution going on, I guess there is. It’s always the same, though, in the beginning. None of the bands sound the same, but they’re grouped in together because it’s rock ‘n’ roll. But we wore the same pants. The bands before us were the nu-metal bands and they had big pants. But we had small pants, the grunge scene was torn pants and the ‘60s, ‘70s rock scene was flared pants. There’s always pants involved.

PM: The one constant in music is that the pants will always change.

PA: A rock ‘n’ roll movement is not about sound, it’s about pants.

PM: Being someone who has seen so many different iterations of rock music over the years, do you think that the genre can have another big blow up like the Meet Me in the Bathroom era that happened in New York? Or has the industry changed so much that, maybe, that type of explosion isn’t doable at the same magnitude again?

PA: I don’t think those explosions come from the industry. They come from fans first. I definitely think it can happen again. It hasn’t happened in awhile. I guess the last rock band to become stadium-sized is Arctic Monkeys. They broke through a while back. Learning an instrument might not be as big with kids today, but something like it will probably happen. It’s timeless fun, playing loud guitars on stage. I hope people still get to experience it, because, when we started out, there was a default way to make music. “Oh, we gotta get a drummer, we gotta get a guitar player, we gotta get a bass player.” Whereas now, most music is made on computers. That’s how you make music. If you’re like, “Oh, I’m interested in making music,” you’ll get a laptop. You won’t have to get friends. That’s why there are so many more solo artists, because a band is a pretty expensive machine to lug around. If you can just have a laptop and yourself, touring is more profitable—you lose less money. Touring is not that profitable. But you can do it pretty easily. If you want to make DIY music now, a laptop makes more sense than forming a band.

PM: Can you sum up The Death of Randy Fitzsimmons in one word?

PA: Rock.

Matt Mitchell reports as Paste‘s music editor from his home in Columbus, Ohio.