Hear Me Out: The Velvet Underground’s Squeeze

Doug Yule did his best to carry Lou Reed's splendid, poptimistic torch, even if his efforts on the Velvets' final album were cursed from the very first note.

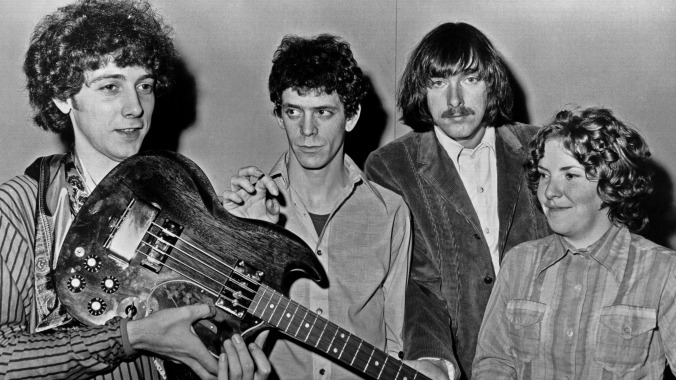

Photo by Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Hear Me Out is a column dedicated to earnest reevaluations of those cast-off bits of pop-cultural ephemera that deserve a second look. Whether they’re films, TV series, albums, comedy specials, videogames or even cocktails, Hear Me Out is ready to go to bat for any underappreciated subject.

I can smell the tomatoes already. But, hear me out. I am not here to label the Velvet Underground’s final studio album a masterpiece or anything of the sort. No, no. Instead, I would just like to say that, hey, Squeeze is not so bad! Yes, in the context of something like The Velvet Underground & Nico—one of the greatest albums ever made—it’s quite deplorable. And yes, in the context of the Velvets’ other three albums (White Light/White Heat, self-titled and Loaded), it’s still bad. But I’m not so sure we should really consider Squeeze in the context of those albums. I mean, is it even a Velvet Underground project at the end of the day? Survey says: No. But, contractually, yes, it is.

To better understand the band’s loathed and reviled 1973 finale, we must first rewind to 1968, when the Velvet Underground released White Light/White Heat. They had lost Nico after cutting ties with their then-manager Andy Warhol, and Warhol’s replacement, Steve Sesnick, was not liked very much by multi-instrumentalist John Cale, who believed that Sesnick was trying to retool the band’s image by presenting Lou Reed as its frontman. If The Velvet Underground & Nico is considered a proto-punk forefather, then White Light/White Heat was the raunchy, chaotic explosion that shattered heavy music’s low ceiling. The band’s performances were harsher and rowdier than ever before, and Cale even described the record as “consciously anti-beauty” in the wake of their debut’s delicate moments, like “Sunday Morning” and “I’ll Be Your Mirror.”

Tensions were beginning to set in quickly, as Reed and Cale both held the brilliance to be bandleaders but had perpendicular ideas. Toss in some serious underperforming sales and lack of overall recognition for the work, and the Velvets were sitting front row on a heat-seeking missile toward self-destruction. One of the last recording sessions to feature Cale showcased this division: three songs were made with Reed’s poppier glint (“Stephanie Says” being one of them), while Cale’s viola-driven drone took center-stage on “Hey Mr. Rain.” By the end of September 1968, Cale was fired from the band. “Lou told [Robert Quine] that the reason why he had to get rid of Cale in the band was Cale’s ideas were just too out there,” Michael Carlucci later recalled. “Cale had some wacky ideas. He wanted to record the next album with the amplifiers underwater, and [Reed] just couldn’t have it. He was trying to make the band more accessible.”

Reed’s desires to make the Velvet Underground a more palatable band after leaving Warhol’s Plastic Exploding Inevitable make sense. He was never so deeply entwined with the avant-garde, at least never to the extent of the virtuosic Cale, and his interests were always far more aligned with the pop world—at least in the 1960s, as some of his solo albums, like the equally maligned Metal Machine Music, are allergic to pop labels. So, as the Velvets were about to start work on their third (and eventually self-titled) LP, Reed hired Grass Menagerie multi-instrumentalist Doug Yule to replace Cale. The story goes that, while he was still living on River Street in Cambridge, Massachusetts (in an apartment owned by the band’s tour manager Hans Onsager), the Velvets stayed at Yule’s apartment after playing the Boston Tea Party.

During their stay, Sterling Morrison claimed to have heard Yule practicing guitar and informed Reed that the young New Yorker was getting better at playing. Sesnick would organize a meeting between Yule and the band at Max’s Kansas City in October 1968, and the idea was to have him join the Velvet Underground as their new bassist, organ player and background vocalist. The new quartet recorded The Velvet Underground between November and December of that year, and it came out the following March.

The Velvet Underground, the People’s Champion of the band’s catalog, was a massive departure from the brash, angry soundscapes of White Light/White Heat. Reed had gotten his wish of employing a gentler sound, one influenced by the historical folk scene that was grabbing national attention in the early 1960s—the same time period that La Monte Young’s Theatre of Eternal Music began doing all-night performances with different permutations, which included Cale, and would inspire the avant-garde roots of the Velvet Underground altogether. And on their self-titled album, Reed was able to pen two of his greatest tracks: “Pale Blue Eyes” and “Candy Says,” the latter of which featured Yule on lead vocals. He and Reed proved to be a formidable (and often overlooked) pop tandem.

Yule would continue to see his role in the band grow, leading to him singing lead on two of the band’s sweetest tunes: “Who Loves the Sun” and “Oh! Sweet Nuthin’,” the bookending tracks on the Velvets’ fourth album, Loaded. While Reed’s “Sweet Jane” and “Rock & Roll” have endured as the two most beloved and “commercial” songs from the band’s penultimate record, I would argue that Yule’s performances are some of the most compelling on the project. The seven-minute closer “Oh! Sweet Nuthin’” is handily one of the greatest finale tracks of its era, especially. Loaded went on to receive scores of admiration and generational praise: Rolling Stone gave the album five stars, while Pitchfork’s retrospective review declared it a perfect 10. Even critic Robert Christgau, whose Village Voice was one of the first publications to write earnestly about the Velvet Underground’s work during the & Nico days, gave Loaded an A.

By the time Loaded hit the shelves in November 1970, the avant-garde, experimental roots of the Velvet Underground had been eradicated. Reed’s pop sensibilities were in full bloom, and Yule’s willingness to play a worthy second-fiddle to him helped shoulder the Velvets into another dimension. But, as rock ‘n’ roll folklore would have it, the band was slowly falling apart. Longtime drummer Maureen “Mo” Tucker received credit for Loaded without playing a single note (except for her singing “I’m Sticking With You,” which only appears on deluxe-editions), as she was on maternity leave during the recording; Reed, fed up with the Velvets going nowhere commercially or critically, had actually quit the group a month before the album came out; Morrison would leave nearly a year later. “I left them to their album full of hits that I made,” Reed allegedly said of Loaded after seeing it in record stores.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-