Tulsa, Oklahoma, and the Legacy of Leon Russell and J.J. Cale

Road Music, Chapter Six

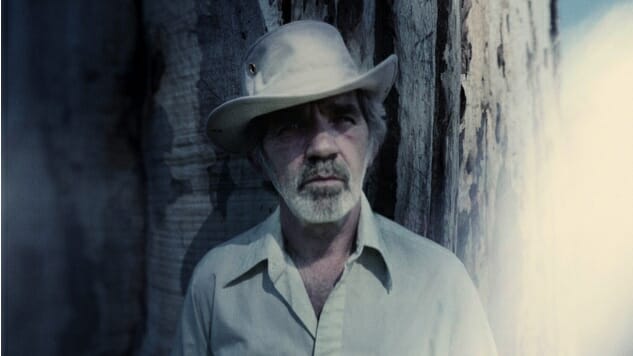

J.J. Cale photo by Stephane Sednaoui, courtesy of Because Records

Three of the most prominent shapers of the Tulsa Sound have died over the past six years: J.J. Cale in 2013, Leon Russell in 2016 and the Tractors’ Steve Ripley just this past January. And yet, when I visited Oklahoma in March, the Tulsa Sound was still thriving, buried beneath national attention in the town’s barrooms and dancehalls.

And that’s good news, for the city’s laid-back brand of rock ’n’ roll, boasting equal measures of hillbilly twang and gospel soul, has been one of the most fertile and enjoyable regional sounds of the past half century. One can make a convincing case that British guitarists Eric Clapton and Mark Knopfler built much of their careers on the Tulsa Sound. Just compare Clapton’s solo work and Dire Straits’ hit singles with Cale’s 1971 debut Naturally and see if the resemblance doesn’t jump out at you.

Clapton, at least, has gone out of his way to acknowledge the debt, declaring in his autobiography the Cale is “one of the most important artists in the history of rock, quietly representing the greatest asset his country has ever had.” Clapton and Cale shared a Grammy Award for Best Contemporary Blues Album for their 2006 duo album, Road to Escondido.

Paul Benjaman and Paddy Ryan (courtesy of Paul Benjaman)

At the Colony, a small bar on a run-down strip of Tulsa’s East Side, Paul Benjaman was playing his every-Sunday-night gig. When he sang, “I’ve got your music singing in my bones” from his original song “Your Music,” the burly, 45-year-old rocker was also acknowledging a debt to Cale. In the same set, he even sang the Cale rarity, “I’ll Make Love to You Anytime.”

But Benjaman was adding to the tradition as much as he was borrowing from it, lending it a more muscular Southern-rock flavor and writing songs as impressive as the deep-groove “Detroit Train” and the pleading ballad “How Bad I Want You.” He would quickly lift his left hand off the fretboard after each chord to give his guitar a pulsing sound. And in drummer Paddy Ryan, Benjaman had a master of the push-and-pull rhythm that undergirds most Tulsa music.

“I got it first hand,” Benjaman said between sets. “I’d sit down and see how the older guys were playing that rhythm that’s the essence of the Tulsa sound. When you hang out with them, they’ll tell you: They would listen to those old blues records where one musician would play a straight beat, and another would play a shuffle. In between those is the Tulsa sound.”

Some of those old-timers are still around: singer Randy Brumley, Cale guitarist Don White, Russell guitarist Chris Simmons, and Clapton/Russell drummer Jamie Oldaker. And they’ve passed on their knowledge to a younger generation that includes Benjaman, Cody Clinton, Seth Lee Austin, Wink Burcham and Dustin Pittsley.

Perhaps Cale said it best when he declared, “We were just trying to play the blues and didn’t know how, so that’s what we came up with.” Just as the Rolling Stones and the Yardbirds were trying to copy American blues records and got it just wrong enough to come up with something new, so did these kids raised amid the empty ranch lands and oil wells of Oklahoma. But instead of filtering the blues through skiffle and music-hall songs, as the Brits did, these cowboys filtered it through country music and gospel—and that made all the difference.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-