The Surprising Parallel Between Tupac and Turkish-Kurdish Singer Ahmet Kaya

(And What It Suggests About Anti-Racism Movements in America and Turkey)

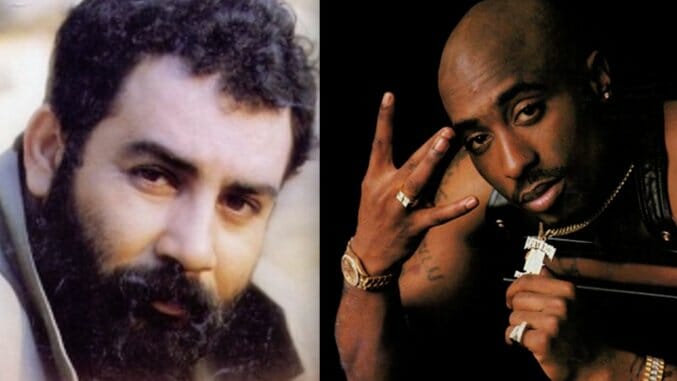

Photos by Death Row/Interscope Records and Tempa & Foneks

“I am first and foremost a revolutionary. (Her seyden once bir devrimciyim ben.)” – Ahmet Kaya

“If I can’t be a part of this country, I’ma damn sure tell everybody exactly what’s wrong with it.” – Tupac Shakur

As I approached the grave of Ahmet Kaya, I saw a woman in front of it, weeping. There’s someone else here? I thought, aghast. The Turkish-Kurdish singer died in 2000 while fleeing political persecution in France and remains buried in Paris’ Père Lachaise Cemetery. What were the chances that Parisians would know Kaya’s work, let alone wish to visit his sixteen-year-old grave? If Westerners are aware of Kaya at all, it’s likely only because his estate accused Adele of plagiarism last year.

But as I paid homage to the site, a stream of visitors did the same—mostly Turks on holiday. I struck up a conversation with that first woman, a Turkish Australian tourist. She was stopping by Kaya’s grave because her father in Turkey was an enormous fan of the artist. She wasn’t very familiar with Kaya’s music herself.

I can’t personally imagine crying at the grave of a musician whose music I don’t even know. But that speaks to the power of Kaya’s legacy: for Kurds he is a symbol of martyrdom and hope in the face of oppression. And Westerners should care about that, especially these days; Turkey’s lingering Kurdish issue is one of the major factors determining the trajectory of the Syrian conflict.

Both Turkey and America are experiencing spikes in racial tension. In Turkey, the collapse in July 2015 of a two-year ceasefire between the government and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), and the subsequent terrorist attacks orchestrated by that organization and affiliated groups, has made anti-Kurdish sentiment higher than it’s been in years. In America, angry backlash to movements like Black Lives Matter is rampant, and Trump’s rise has empowered white supremacist groups.

Ironically, these escalating tensions coincide with surges of appreciation of two of the countries’ staunchest anti-racist musical voices: Kaya and Tupac Shakur. The former has become widely beloved in Turkey; just a few years ago then-president Abdullah Gül awarded him a posthumous Presidential Grand Art and Culture Award. Tupac has just been nominated for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. The recent musical Holler If Ya Hear Me dramatized his life, and there’s a movie about him in the works.

It’s remarkable that these two artists have mainstream appeal while the issues about which they sang and rapped are still discredited by the majority. Make no mistake: that was not always the case; during this period of popular and critical acclaim it’s easy to forget just how controversial these figures were in their day. At the times of their deaths—Kaya in 2000, Tupac in 1996—these men were the subject of active hatred from enormous swaths of society and hostile coverage by much of the media.

Kaya was even subjected to a government-sponsored effort to suppress his music. His first album was filled with messages of political discontent about Turkey’s oppression of its Kurds (who make up about a fifth of the population). At that time, in 1985, it was illegal even to speak Kurdish. The album was promptly censored, as were many of his later records. In 1999 he faced persecution after announcing that he wanted to record a song in Kurdish. He fled to France, where he died of a heart attack for which many blame the stress of decades of terrorization from the state.

Kaya and Tupac have a surprising amount in common: first, both spent time in prison—Kaya was jailed many times because of his music and Tupac once for sexual assault. Tupac maintained that the allegation was baseless and an attempt to frame him.

Both were routinely accused of promoting racial divisiveness. Ahmet Kaya was charged over and over, and still is, of having links to the PKK. In 1994 a young man who’d killed a police officer said that he was inspired by Tupac’s lyrics, some of which reference violence against police. Tupac’s parents were members of the Black Panther Party; Tupac said of the controversial group, “I think that they were successful because they bred me.” A 1995 headline about Tupac in the Michigan Quarterly Review asserted that he “brings bad image to blacks.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-