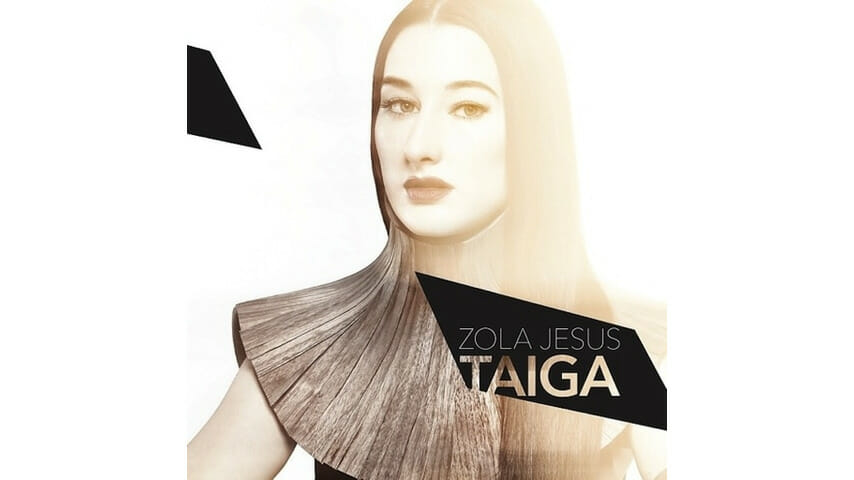

Zola Jesus: Taiga

I really like Zola Jesus. I want to really like Zola Jesus. In the past, I’ve felt about her records the way Rose McGowan seems to feel in The Doom Generation when she stares into the cover of Blood by This Mortal Coil, saying, “I wish I could crawl in here and disappear forever.” Zola Jesus’ records feel like a digest from a barren, rough and synth-scored world I’d rather live in, continuing a massive tradition in goth-pop of creating something dark and brooding but accessible, making something beautiful out of ugly things.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-