The Sonic Exchange: An Argument for Crafting a More Just and Sustainable Market for Music

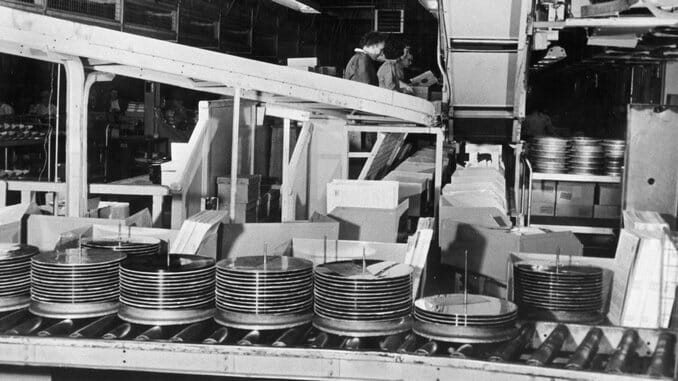

Photos: Hulton Archive, George Marks/Getty

The American music industry does not frequently garner great recognition as a player in the overall economy, but it has firmly made its stake as a capitalist entity and exemplified its adaptability to the rapidly changing technology of recent decades. It seems as though the halcyon days of music exist in a haze of hardworking, self-sufficient artists, but the truth reveals that the recording industry at large has been one of exploitation and unfair treatment of musicians since its genesis. The nature of the music industry and its generation of popular music and artists parallels the trend of the “throwaway economy,” marked by cheap goods that are not built to last. Suited for the current fashion, their obsolescence in the music scene is planned.

Major music labels such as Universal, Sony, and Warner dominate the industry, but as we progress further into the digital age, small, independent labels have gained traction—cornering a part of the market that caters towards musicians that have yet to be “discovered” on a larger scale. This notion presents an interesting aspect of the musical economy that corresponds to the overall economy: stagnation means failure, growth means success. From the smallest of independent artists, to the most well known, frequently touring acts, the song remains the same; the end-goal is large success and a multi-million dollar record deal. Perhaps this trend could be blamed on culture, pop-icon idolatry, or a deep-seated quest for personal fulfillment – perhaps the blame better falls on the teachings of capitalism and a growth based-economy. The commodification of music and artists’ work is indicative of the exploitive practices of capitalist ventures, the current nature of the musical economy is simply not working for the majority of those who are operating within it. However, in many circles within the musical economy, artists are beginning to take back their space, their music, and their creative means.

In the past decade and a half, the popularity of digital music has skyrocketed. Since the introduction of the Apple iPod in 2001, the entire perception of music buying, selling, and sharing has experienced a great shift. With the introduction of the online music economy, singles released by artists and record labels could be sold individually on a large scale with no need for physical media. Spotify, Apple Music, and online radio such as Sirius and Pandora now dominate the non-physical music marketplace. While fans widely appreciate the free or low price streaming services, artists and labels both big and small are experiencing an economic slump. Many artists are beginning to rally against free music streaming, and some are going so far as to create their own, more ethical method of music streaming. Free online streaming is largely an answer to the growing problem of music piracy. Adapting to the changing culture of music consumption was a critical move for the music industry. Artists who feel cheated by online streaming services are still operating within capitalist values – perhaps if the musical economy were to shift into a more community oriented, sharing-style economy, there would be more contentedness among artists.

In the age of digital music, it would seem that physical media would no longer be a point of attention for record labels. However, Record Store Day (RSD) is a national biannual event that arose in response to failing record stores and decreasing physical media sales in the mid-2000s, when many record stores began to shut down. The event garnered huge success, grabbing nationwide attention and gathering larger numbers of RSD customers each year. In 2014, vinyl record sales reached an all time for the past two decades. However, the twice-yearly event began to receive more criticism as it gained success, its decriers are owners and patrons of small, independent record stores. The popularity of RSD has created a difficult situation for many independent record store owners who may not be able to afford the venture capital it takes to purchase special RSD releases, especially when they are not sure if they will sell out their stock or be fated to keep boxes of it in their storerooms, accumulating dust as they depreciate in value.

In 2008, seven independent Swedish music labels formed an alliance intended to transform the musical economy. The premise of their restructuring model was to encourage the sharing of free music, rather than fighting the losing battle against it. The valuation of musical creations as sellable units detracts from what many consider to be the purpose of the creation of art.. The intersection between art and money often results in frustration, disillusionment, and feelings of betrayal and exploitation. Artists become trapped in contractual obligations to record labels that capitalize on their creativity, selling their music for profit while the artists are left without a feeling of satisfaction.

The practice of selling creative “goods” intrinsically diminishes the meaning of the work – by putting a price on a song, album, or discography, the artists’ work becomes subjectively capitalized and commoditized. The meaning behind the work becomes abstracted by the price that is placed upon it. By refraining from the pricing of musically creative goods, the focus is shifted away from the monetary success of the artist unto the creative and community impact of the artist. It focuses on the influence that they may have on the overall well-being of the community and its members. Within the Swedish Model, a key component is the ease of which fans can find and listen to bands, which generates positive feedback for the artists, labels, and producers. When the songs are given away for free – as gifts – their value becomes entirely determined by the listeners, how much that song gets shared thenceforth reflects the intrinsic value of the song.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-