Be More Human: Fighting Homelessness on the Front Lines

Photos by Lindsay von Werner

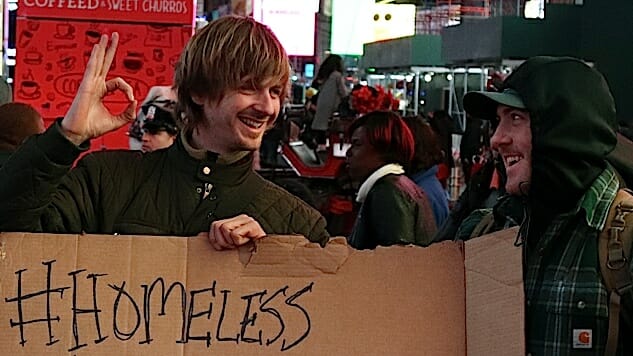

Bathed in the flickering glow of Times Square’s innumerable billboards, Andrew Funk looks down, scrutinizing a sign he’s made from dumpstered cardboard and permanent marker.

“50,000 Tourists in Times Square every day, but 5,000 homeless sleeping on the streets,” it reads. The actual number of homeless living on New York City’s streets is closer to 3,800; but when we call this to his attention, Funk fixes us with a look and sucks his teeth. Then, shaking his head and breathing a deep sigh, he kneels down and adds a “+/-” ahead of the 5,000.

“Happy?” he asks, his voice betraying apprehensive frustration, as though asking himself, ‘Are they going to be like this the whole night?’

The 36-year-old founder of Homeless Entrepreneur, an international charity that connects homeless individuals with teams of professionals to help them become economically independent, looks a little like a younger, leaner David Spade coming off a bender. He’s got shaggy, dirty blond hair hidden under a “New York” beanie he purchased from a street vendor. His chin is covered in thick stubble, and his eyes are adorned with heavy bags. Relaxed and analytical, Funk handles every interaction with a professional directness. He doesn’t have a lot of patience for what he deems extraneous.

He’s here in New York City’s relentlessly illuminated commercial heart on a mission. We’re getting caught up in minutiae.

Funk battles on the front lines of a worsening crisis spreading across America. Last year saw the first rise in homelessness nationally since 2010. While there are immediate causes which can be identified—a growing wealth gap, wage stagnation in the face of rent increases, the boom in luxury development, the rise of short-term rentals, and the decline of rent control—solutions are elusive, as they necessitate macro policy changes that run afoul of powerful interest groups.

New York’s metropolitan area has a particularly bad homelessness problem despite being the wealthiest city on Earth. It’s why we’re here tonight. In 2017, the Big Apple was home to one out of every five homeless individuals recorded in the US. Unsurprisingly, it has been a hub for luxury development, in part because developers can take advantage of the city’s affordable housing tax breaks. The city also boasts the largest short-term rental market in the country, accounting for 2.1 percent of all its housing stock. Landlords today are incentivized to evict or buy out tenants in rent-controlled apartments so as to cash in on the free market.

A few feet away, Funk’s companion, Jake Strickland, who has been working on his own signs, looks on amused. The 32-year-old active duty U.S. Army recruiter from North Carolina has the appearance of someone you’d expect to have carried his high school lacrosse team all the way to State—we didn’t ask. Strickland founded Cardio Blessings, a North Carolina-based Christian nonprofit, to help the homeless after a combat injury landed him stateside. He, along with co-founder LaDarren Landrum, organize walks through cities across the country to provide both immediate and long-term assistance to the destitute. They distribute “survival packs” containing everything from clothes and food to feminine hygiene products. Their long-term support involves “building a team… and forming a professional community around those individuals and their specific needs.”

“Don’t forget to put your logo on there,” Funk says in Strickland’s direction, catching his amusement as he kneels to scribble “#HomelessEntrepreneur” on his own cardboard. Standing back up, he turns to us. “I know how you can be useful. Take this sign and stand where there’s plenty of [pedestrian] traffic.”

It’s freezing—the kind of cold you can almost taste—but Funk barely seems to notice. We’re here for a sleep out, and it’s all hands on deck.

As the name suggests, sleep outs are events where volunteers spend a night outside to raise money and awareness for the fight against homelessness. They have grown in popularity over the last five years or so, with a number of charities and organizations deploying the tactic.

At their highest aspiration, sleep outs are a show of solidarity with the homeless; a higher commitment version of the Ice Bucket Challenge, inspiring people to get involved. But, the events have also faced criticism for perpetuating “the myth that homelessness is about rough sleeping,” and thereby minimizing the larger issue.

The previous night, we visited Hell’s Kitchen for a “young professional edition” sleep out at the Covenant House New York shelter for homeless youths. In a cordoned-off parking lot, complete with a security guard and access to the indoor bathroom, dozens of attendees laid in rows inside red nylon sleeping bags, most staring into iPhones. We were barred from entering, speaking with any of the participants or taking photographs. The whole event felt a bit surreal—a bizarre kind of poverty tourism, or worse: a networking event for young professionals.

But the sleep out tonight is something else entirely. There are no guards, no bathrooms, no complimentary sleeping bags, and no cordoned off parking lot. For Funk and Strickland, this event is about more than holding signs or experiencing a night on the streets; it’s about finding potential candidates. And that means, seeking out and engaging with the homeless.

Funk had organized this particular event with Strickland after connecting online, but he does these events every month. Sleep outs are great for outreach and raising awareness. And for the 36-year-old, they are about something more—a sort of homage to the year and a half he spent homeless in Barcelona before founding his nonprofit. The experience, he says, made him “more human”:

“I was homeless myself for a year and half. I had to solve my own problem. And after I solved my own problem, I wanted to help other people solve their problems.”

Sometimes, that can be as simple as offering part of his barbequed chicken dinner to the street poet who approaches us, offering a performance in exchange for “anything [we] can spare.” Other times, it can be more involved, like sitting down for a forty-minute interview with the homeless photographer who saw our signs and clearly wanted to tell his story. “Are the homeless bad people?” is the first question the man asks, seemingly searching for any sign of prejudice. Funk is able to assuage his concerns by opening up about his own past.

“It was supposed the best moment of my life,” Funk tells the photographer. “We raised €300,000 to start a company, and I was about to have my firstborn son. One of the partners mismanaged the money; they smoked it all away in six months, and the economic problems caused problems at home. So economic problems…family problems. I decided to leave my home, so my son wouldn’t be in a negative atmosphere; and that’s how I ended up homeless without even knowing I had entered homelessness.”

A few minutes later, the two men are laughing about the myriad challenges involved with “taking a shit” while homeless. Funk shares a story of a night on the streets of Tarragona, Spain, involving bad lentils and necessary public defecation between two parked cars— for privacy. The anecdote sounds trivial, but Funk goes on to explain the pernicious psychological impact such indignities can have on a homeless person:

“The problem is when you accept that indignant response. When it becomes the best solution, that’s sad. That moment when it’s acceptable to you to shit between two cars because no one would let you use the bathroom is sad.”

Looking around at his audience, he declares, “Going to the bathroom should be a human right!” All parties vigorously agree.

Funk approaches every interaction as if the individual he’s engaging with has “something of value” to offer. He’s doesn’t interrupt. He doesn’t judge. He doesn’t pity. But he does ask hard questions, and he demands honesty and directness.

“The first time I saw him talk to someone, I was a little like ‘woah, did you really just ask that?’” Stickland tells us, shaking his head and smiling. “Like, if someone asked me some of that stuff, I’d be like, ‘are we going to fight right now?’”

But Funk’s sure of his philosophy—which is good enough for his companion.

“When you treat someone like your brother, you take care of them,” he explains. “But, when you say they’re homeless they’re another. They’re not part of you. They’re them. So when you say they’re part of you, you can’t treat them like that. And that’s what we’re trying to do: get people to understand that homeless people are people. Homelessness is a situation; but they’re people, and you should take care of them like people.”

However, he adds a caveat: “It’s bidirectional. They have to participate as well. So you have to work in a relationship with them.”

We catch a glimpse of this expectation of mutuality in an interaction Funk has with a dirty looking kid sitting on the sidewalk holding up a sign:

LOST BOTH PARENTS MY HOME

AND MY JOB IN THE PAST YEAR

NOW I SLEEP ON THE STREET

AND STRUGGLE DAILY

ANYTHING HELPS THANK YOU & GOD BLESS

The kid’s got sad, glazed-over eyes, dirty blond hair, and a cup full of change in front of him. We can’t agree on his exact age, but we suspect it’s somewhere around 20. “Do you mind if I ask you some questions?” Funk leads off, extending a hand. Tobacco stained fingers reach out and close around it, and he nods.

Funk proceeds, inquiring how long he’s been living on the streets. Six weeks. Does he do any drugs? No. And then, as if probing the kid’s readiness to be honest, how much does he generally make in a day?

Pausing, the kid tells us it “depends on the day.”

“A good day,” Funk clarifies.

Another pause. The kid wrinkles his nose a little, looking slightly uncomfortable, before giving us a figure. “Around one hundred and fifty.” Funk, seeming satisfied with the answers, invites him to spend the night with us and tells him about his program. “But I understand if you want to keep your spot,” he adds. The offer is declined, so we drop $15 in the kid’s cup and turn to leave.

Watching this play out from the sidelines is somewhat jarring. We turn to Strickland, who does not seem fazed. “I know, right?”, he chuckles. He’s been watching Funk intently and learning.

Walking away, we notice the kid pocket the $10, leaving the $5 bill in the cup. Funk turns to us, as if he’d noticed our discomfort. “That’s a kid who’s not ready for help,” he whispers. “Did you see his eyes? How out of it he seemed? Drugs. Likely heroin. That’s a kid looking for a handout.”

He would not be a candidate for the Homeless Entrepreneur program, which Funk proudly tells us has a 33 percent success rate.

Funk’s hands-on approach is unusual for this city. New Yorkers encounter homelessness every day, walking down busy streets or descending into hellish, overcrowded metro stations and subway cars. Panhandlers scout for approachable travelers. Huddled bodies in faded clothes shamble by pushing carts or sit just out of the way, on cardboard, asleep or completely disengaged, sometimes behind signs, eyes haunted. New Yorkers learn from an early age not to interact or get too invested in the lives of the homeless. Homelessness is seen as an intractable problem beyond our ability to solve because ‘some people just cannot be saved.’

It’s easy to see why this attitude is so pervasive. Ever since modern homelessness first appeared in New York City in the 1980’s, City Hall has been throwing money and various solutions at the problem to no avail. The number of people living on the streets grew by 39 percent in 2017. A stunning 129,803 individuals, including 45,000 children, slept in the city’s shelter system, a majority of whom were mentally ill or living with serious health issues, and a disproportionate number of whom were people of color.

Based on the data, it’s clear the solution is going to involve aggressive reform on the national level. Two recent studies—one from August by the Urban Institute, and another from May by United Way ALICE Project—found that a majority of Americans struggle to afford basics like food and rent. Most full-time workers today live paycheck-to-paycheck and are in debt. High medical costs do not help matters either. A medical emergency of $1,000 emergency is cost-prohibitive for most Americans. Yet, a 2016 study from the Kaiser Family Foundation found half of all health care policyholders faced deductibles of over $1,000. As one might expect, medical bankruptcies are a common occurrence.

But these statistics only make for passing conversation as we try to keep warm against the night, wrapped in sleeping bags outside of American Eagle, acutely aware of passing footsteps. Funk and Strickland don’t worry too much about bigger policy questions. They recognize the benefit of the work they do, but know the limitations as well.

The next morning, as we’re packing up to head to the nearby McDonald’s for breakfast, a gaunt figure, seemingly out of George Romero’s “Dawn of the Dead,” approaches us. In his left hand, he holds a large painter’s bucket with his possessions—an open bag of chips, a pair of drumsticks, a two-liter bottle of fruit punch, a worn pair of flip flops, and balled-up hoodie. He is most certainly homeless. His darting eyes, calloused skin, chest length beard, and slight odor indicate that he has been for some time.

Without hesitation, Funk greets him, extending a hand and an offer to join us for a hot meal. From the look on his face, it’s clear the man is surprised. His expression warms in one of deep gratitude as he accepts. His name is Dwight.

“Pleased to meet you,” he says in a soft, gravelly, mumbly voice.

The logistics of bringing a homeless person to breakfast are dicey, even at a McDonald’s. As we stand in line, people clear a five-foot circle around us, turning away as if we had just walked in with an Ebola patient. When we ask to use the restroom, we are told it’s “out of order,” despite the fact that another patron had just walked out. In his conversation with the photographer, Funk had discussed the psychological toll the indignities and alienation associated with homelessness take on a person, and at this moment, it’s playing out in front of us in real time.

Sitting down with our coffees and McMuffins, Dwight tells us he’s a veteran who served from “‘87 to ‘93,” and suffers from PTSD from his time abroad. “I just turned 53,” almost whispering. “I’m not that old, but I’m kinda old. Everybody else is kinda young.”

A few minutes later, the conversation shifts to what life is like for someone like Dwight on the street. Did he ever get harassed? Was he generally safe?

“Everybody in this neighborhood knows me,” he replies. “It’s different when they know you. They say good morning and everything.” He goes to note the high police presence.

Funk presses, asking if he’s heard about violence towards the homeless elsewhere in the city. This question elicits a serious expression.

“Oh, other parts, it’s bad,” Dwight muses, nodding emphatically.

Funk just shakes his head. “I’ve never understood man. I’ve been doing my thing a year and a half, or two and a half years…I will never understand how someone could steal from a homeless person.”

“They do it,” Dwight replies, words hanging in the air. “Trust me, they do it.”

In moments like these, the broader questions about inequality and policy fall away, and our hosts’ motivations and methods make perfect sense. Funk and Strickland are tired of waiting for political leaders, torn between interest groups, to tackle the problem. So, they’re taking it upon themselves to make what difference they can, one individual at a time. Getting into the cab after saying our goodbyes, knowing that our hosts have a full day ahead of them, Funk’s words are still playing over and over in our heads: “Provide something of value” and be “more human.”