No Joking Matter: The Emmys, Les Moonves, and the Shallowness with Cultural Progressives

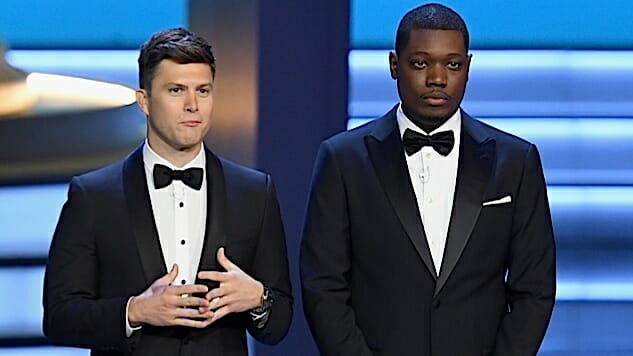

Photo by Kevin Winter/Getty

“It’s the Emmys. It’s about television. What’s the biggest story in television? The fact that the president of CBS had to resign … Me Too is in the news. They talk about Me Too, but they don’t talk about Les. I mean, my goodness. That means they’re afraid of him.”

— Howard Stern

Joking about a thing does not make you immune from it. It is not a replacement for the hard labor of change. The entertainment industry doesn’t seem to have gotten the memo.

Speaking of memory, it was swell of the Emmys to give Les Moonves a retirement gift last week. The show made a to-do about sexual harassment claims, or pretended to:

[Colin] Jost jumped in to add, “Netflix has the most nominations tonight. If you’re a network executive, that’s the scariest thing you could possibly hear. Except for, ‘Sir, Ronan Farrow is on line one.’”

Despite the title of the Hollywood Reporter story (“Emmys Opening Monologue Takes Jab at Leslie Moonves”), nobody saw fit to mention the former CBS honcho. Someone even made a supercut of all the Les Moonves digs at the Emmys. Spoiler: It’s a short video.

All that performative irreverence, and the hosts couldn’t crack wise about the one large, looming shadow in the room? It wasn’t as if they hadn’t heard. According to the Reporter, it was the rage backstage:

Talk of Les Moonves proved inescapable as industry insiders huddled to exchange opinions about the exit of the CBS chairman and CEO who resigned Sept. 9 following back-to-back New Yorker investigations by Ronan Farrow that detailed sexual misconduct and harassment accusations from a dozen women.

The lack of follow-through was so obvious, the New York Times noticed it:

The 70th Primetime Emmy Awards opened Monday night with a little soft-shoe self-deprecation, a semi-musical number called “We Solved It,” in which a chorus of television stars claimed that their industry’s diversity problem had been overcome … Not content to say it in song, the show then emphasized the point by handing out its first 10 awards, and 22 out of 26 overall, to white performers, directors, writers and producers. The host Michael Che made a joke about it after six awards, James Corden after nine. The tension and embarrassment in the Microsoft Theater were palpable when an African-American, Regina King, finally won, for best actress in a limited series in Netflix’s “Seven Seconds.”

Why wouldn’t it occur to the Emmys to mention Les Moonves? Why, for the same reason they give awards mostly to white people. The Emmys are the Nike of television programs. They make their living by pretending to be more progressive than they actually are.

The award show points to a problem of progressive culture. These days, joking about injustice is methadone for progressives. It’s what you take when the real thing bothers you.

If progressive comedy and progressive culture was what it pretended to be, it would be useful. But the absence of Moonves quips, and the preponderance of white Emmys, shows why cultural progressivism is so shallow.

The problem with progressive culture, specifically comedy, is that it’s a business. This business is extremely profitable. Concentrations of power own practically every entertainment platform. The agenda they propose is pro-business.

However, the audience for most entertainment is non-business. In general, the public backs progressive issues. And, as the National Review is constantly kvetching, the people who staff these platforms are generally progressive. That’s the essential dynamic of entertainment.

Faced with this tension, between opposing powerful, moneyed interests, and playing to their audience, you get … well, what you saw at the Emmys. Words that are progressive. Acts which are conservative.

The result? Entertainment made by progressive people for a largely progressive public … that doesn’t amount to much. It’s Jon Stewart acting shocked. It’s Samantha Bee, pretending to care. It’s Trevor Noah, John Oliver; it’s Seth Meyers, explaining outrage but not doing much about it. It’s David Cross, dedicating an entire album to ranting about conservatives and then saying racist things and defending Jeffrey Tambor. Indeed, we see how banal and middle-of-the-road most of these people are when a guy like Kaepernick comes along.

Why do the Emmys feel awkward? Because award shows are the moment when we are reminded—by the industry itself—of the huge gap between what they say and what they do.

Centrism, the official religion of American mass media, is wary of standing up to oppressive power. This is partially due to a fear of confrontation. But it also has to do with ideology. Centrists believe in institutions.

When you’re speaking about entertainers, these fears are doubled. Their lives are dedicated to getting audiences to love them. They believe in the institution of the stage and the institution of the screen.

The entertainers known as comedians are no different. The sooner we stop thinking of them as brave truth-tellers, and start thinking of them as hustling troupers, the better for all of us.

We need to regard comedians the way we do politicians: with natural skepticism. Consider the moment in August, when Louis C.K. tried to slither his way back onstage at New York’s Comedy Cellar. As Vulture reported,

The short set was his first appearance after he released a statement in November admitting to sexually harassing five women following a New York Times exposé. Two women who sat through C.K.’s set told Vulture that though the small venue’s audience was overwhelmingly supportive of the comedian, one joke about rape whistles was “uncomfortable,” and that there seemed to be a divide between how men and women reacted to C.K.’s presence.

Paul Tompkins said what a lot of people were thinking:

I knew he’d be back, but I honestly gave him too much credit; I really thought he’d just drop an hour set, Horace & Pete-style, and most of it would be about what happened and what he “learned” from it and so forth. But naw?

— Paul F. Tompkins (@PFTompkins) August 28, 2018

It’s almost as if his entire, well-honed, self-deprecating, self-flagellation act that helped him connect with mainstream audiences was complete bullshit!

— EdgarAndTheHall (@EdgarandtheHall) August 28, 2018

It’s a shtick, folks.

And not surprising. People who live for applause, or to get a laugh, or any reaction, are anxious about getting booed. So no wonder they’re terrified of offense. Or of challenging people who really could make their lives difficult. Ever wonder why you never see Bill Maher or Dennis Leary standing on the barricades? No matter how loud, or irreverent, or rude comedians appear … no matter how much they talk about not caring … no matter how much they boast about telling it like it is … not much has changed since the Middle Ages: jesters are still kept creatures.

I think of Jimmy Fallon as the incarnation of this Switzerland principle. Fallon’s infamous hair-mussing of Trump isn’t just the sign of a toothless political entertainment. It was the instinctive behavior of a man who has always played it safe, and shows the inherent impotence of comedy when it comes to changing society.

A group of people who live for applause, who are terrified of booing, whose careers are sponsored by wealthy sociopaths, who are dependent on the goodwill of advertisers, and whose job is to encourage passive audience consumption, will not lead a revolution. Or fight for marginal change. At best, they can encourage people to do the right thing.

You know what else can do that? The truth.

And the version of the entertainment industry that we saw the other night has no traffic with truth. When you can’t talk frankly about problems, what remains? The Tonight Show.

It’s nice to think you can laugh injustice into the grave. In the real world, action is required. Fallon, and all the Fallons and Josts, will keep a safe distance away from what matters. No great loss. In the real world, justice will have the last, and best laugh of all.