I Am a Whistleblower, and America Needs More Like Me

Photo by Adam Berry/Getty

I’ll never forget the exact moment that I learned what a whistleblower was.

On March 13, 2011, I worked with hacker collective Anonymous to orchestrate a leak of Bank of America emails hinting at rampant fraud in the force-placed insurance industry. In the oncoming weeks as I hid in my room desperately seeking answers for what was happening to my life, a man on Twitter used the term to refer to me.

I am a whistleblower—the word terrified me as I typed it into Chrome and it autocompleted the sentence, “whistleblower found dead.”

The term hung over me like a black cloud for several years. I knew I was blacklisted. Having spent my entire adult life working in the banking, mortgage and insurance industries, there was no way I would get another job. My experience, career and everything that I worked for was flushed down the drain as I was forced to reinvent myself and start from square one to earn a living and survive.

Whistleblowing isn’t something they taught in school. It didn’t come with an instruction manual, and there were few resources available to help me understand it. As I wrestled to come to grips with my new reality, my old one crumbled around me. I lost my house, my car, and, struggling to keep up with my bills, was forced to move back in with my parents at the age of 30.

My family judged me, as did many of my friends. My heart nearly broke as someone I once trusted told me, “nobody wants to be associated with a whistleblower.”

Pride of a Whistleblower

That’s a grim way to start an article encouraging the act of whistleblowing, but it was my reality at the time. My pride took a lot of hard hits in those early days (to be perfectly frank, I still sometimes fight back tears talking about it), but I held onto the whistleblower term. I started a blog so I could document my life and justify my existence, and I stayed active on social media so people would know it wasn’t suicide if I died.

While the banking industry could discredit me, the information was out for the world to see. While working to get a hold of journalists, regulators, and anyone who would listen, it occurred to me that I was fighting an impossible battle. I was an expert in a very specialized subsection of my industry, but was constantly challenged with questions far beyond the scope of what I was trying to expose.

Early in my journey, I made an important decision that would guide the rest of my life and lead me to where I am today. I’m not an expert in all things financial, and there was no way I could beat the banks at their own game. The entire economy is an imaginary construct—they could just change the rules to adjust to me. I’m fighting the house, and the house always wins.

Being a whistleblower, however, I’m in a unique position. I don’t need to be an expert in anything other than myself, because I chose a path that very few people do. Like your drama teacher who failed to get a starring role in Broadway or Hollywood, I can teach the next generation the tricks of my whistleblowing trade to change the world in a different way.

Path of a Whistleblower

One of the many existing government regulations that President Trump vowed to remove since his election is the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (more popularly referred to as simply Dodd-Frank). The act was signed into law by the Obama Administration following the 2007 financial crisis to end bailouts, create the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and provide an SEC whistleblower bounty program that rewards whistleblowers with 10-30% of funds recovered from their tip.

It’s a band-aid meant to correct the problems created when the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Financial Services Modernization Act of 1999 repealed important provisions of the Glass-Steagall Banking Act of 1932. Unlike the Sarbanes-Oxley Corporate and Auditing Accountability, Responsibility, and Transparency Act of 2002 which was passed in the wake of the Enron and Worldcom scandals, Dodd-Frank is aimed directly at financial institutions.

At its most basic level, Glass-Steagall provided separations in investment banking, consumer banking, and insurance. Gramm-Leach-Bliley removed these protections, and we ended up with mortgage-backed securities, which were blamed for the 2007 financial crisis. Dodd-Frank put power in the hands of both the government (the SEC and CFPB) and citizens (as whistleblowers) to keep the banks in check.

Because insiders at companies are financially incentivized to blow the whistle to the SEC, the consensus is that more people will be encouraged to stand up and alert the authorities when they see something wrong. The problem I experienced when attempting to blow the whistle to the SEC (and I’m far from the only one), is that the SEC doesn’t have time to investigate everything.

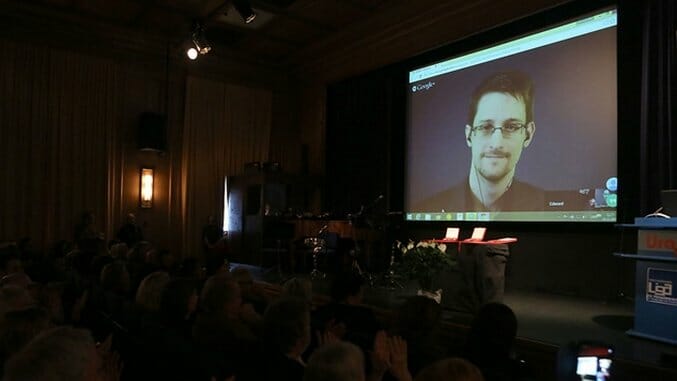

The SEC itself isn’t financially incentivized to pursue investigations based on whistleblower tips unless it feels that it can recover enough money and make enough headlines using as little time and money as possible. It also focuses mostly on accounting fraud, which is no help to a government whistleblower like Edward Snowden or an environmental whistleblower like Erin Brockovich. In fact, the entire program basically ignores any ethical violations beyond those that can be uncovered through forensic accounting.

Several nonprofits exist to help fill in the gaps, including the National Whistleblower Center and National Whistleblower Legal Defense and Education Fund—which collectively run whistleblower.org. However, even these groups have strained resources and can only pursue cases that can win large sums of money in short periods of time. These organizations are so strapped for cash and volunteers that they’re selling The Whistleblower’s Handbook, which puts a paywall between you and vital whistleblower defenses.

If the government (and its taxpayers) were financially harmed by the act committed, you can also file a Qui Tam lawsuit to sue the organization on behalf of the government. This is allowed by the False Claims Act of 1863, also known as the Lincoln Law, as it was passed in response to massive fraud by government contractors during the Civil War. To do so, you’ll need a Qui Tam lawyer, as filing on your own is unlikely to be successful.

I contacted all of these groups, and, while they were supportive and encouraging, none of them were able to help. My problem was that, although I was an employee of Bank of America through its acquisition of Countrywide after the financial crisis, I worked for an insurance company subsidiary of the bank. While banking and mortgages are federally regulated, insurance is regulated at the state level.

To pursue my crusade against the force-placed insurance, I had to step outside the box, forego any financial compensation, and go door-to-door to regulators across the country.

In the years that followed, I worked with my state Attorney General (which was rolled into the $25 billion mortgage servicing settlement), the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (who just last year finalized a very diluted version of the mortgage servicing rules that I suggested), the New York Department of Financial Services (who slapped the banks on the wrist), and the Federal Housing Finance Agency (whose Office of the Inspector General recommended a lawsuit against the banks that never happened).

None of these regulators were ever mentioned in any of my whistleblower research because they don’t offer those sexy million dollar rewards. All I was offered in return for my services was a thank you, and that would be enough if any of them had done what was necessary and eliminated the entire force-placed insurance industry.

The mortgage industry has regulators convinced that force-placed insurance, a proprietary form of insurance that typically only covers the lender, is a necessary product to protect everyone. It’s not—what should exist in its place is a nominal service charge (roughly equal to an overdraft fee) for the lender to obtain property insurance from a consumer insurer.

Force-placed insurance is placed on a collateral loan (home, car, RV, boat, etc.) by the lender when you fail to pay your premium. There’s no reason these lenders can’t obtain a policy from well-known insurers like Farmer’s, USAA, State Farm, etc. They choose to use shadowy companies that you’ve never heard of like Balboa, Newport, and Assurant, despite them making tens of billions of dollars.

If I were to be paid 10-30% of the money recovered from this fraud, I’d be the world’s first billionaire from whistleblowing, but that’s not why I’m in Forbes—that’s never going to become a reality. What’s more likely is that I can convince you to become a whistleblower too.

Plea of a Whistleblower

A lot has changed since that day in 2011 when I contacted Anonymous—not just in my life, but the world in general. The force-placed insurance company I worked for was sold by Bank of America to QBE and then sold again, and most of the staff is no longer there. Ben Lawsky stepped down from the NY DFS, and most Attorney’s General have changed places multiple times since. We have a new President in place who’s working to dismantle the CFPB.

Former Anons and activists like Cassandra Fairbanks are now unmasked and playing for the other side. Many of those who didn’t end up in prison like Barrett Brown are now part of the power structure they once vehemently opposed. In a short six-year period, the world appears to have gone topsy turvy, and that means a new generation must step up.

There are a lot of young people who want to make a difference, and becoming a social justice warrior isn’t the way. SJWs are infamous for their finger-pointing, conspiracy theories, and calls for anarchy. While passionate, an SJW is incapable of changing the world—instead appealing to the powers that be to change. You don’t want to be an SJW, you want to be a whistleblower.

Whistleblowers become the change they wish to see. Rather than simply pointing out problems with a catchy slogan on a sign, we closely examine them from inside the organization, and we put in the work to fix these problems. We speak up when asked to do something that violates their sense of ethics, and if the organization won’t fix it, we roll up our sleeves and do it ourselves.

I’m not an activist or a random SJW. I didn’t stand on the streets outside the buildings of power chanting for change. I walked right in, asked for the person in charge, and filled out the proper paperwork to make it happen.

I am a whistleblower, and you should be one too.