Vineyard Theatre’s Miriam Weiner Talks New Play Development

Vineyard Theatre

For almost forty years, the Tony Award-winning Vineyard Theatre has been a fixture on the Off-Broadway theatre scene, producing premieres of landmark works like How I Learned To Drive, Three Tall Women, The Lyons, Middletown, and Avenue Q, both on Broadway and at their theater in the heart of Union Square. “Dedicated to new work, bold programming and the support of artists,” the Vineyard’s dedication to new work has remained consistent season-to-season.

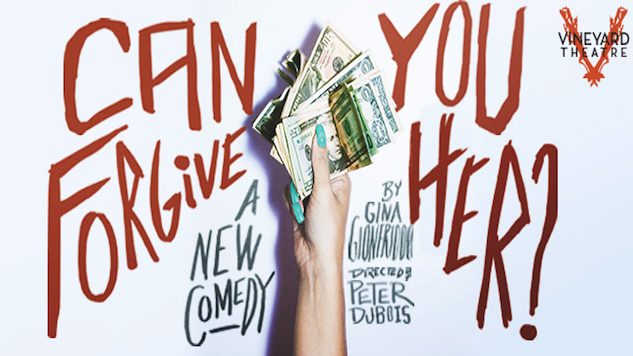

With their production of Paula Vogel’s Indecent now on Broadway, and the Off-Broadway premiere of Gina Gionfriddo’s Can You Forgive Her?, a Halloween-night tale of a woman drowning in debt, opening in May with Amber Tamblyn, we talked with Literary Associate Miriam Weiner about how a literary department operates and what they look for in new plays.

Paste: Could you tell me a little bit about Can You Forgive Her?

Weiner: It’s more interesting to me know even than when we decided to do it, because it’s really talking about the state of America and what’s happening with the middle class and the American Dream. Where people find themselves. And it’s funny—it’s very, very funny… It takes place in this little seaside resort town that’s not what it once was, and everyone’s sort of trying to figure out their best options.

Paste: Gina Gionfriddo’s good at that; balancing the dark humor elements with facades that aren’t quite what they seem.

Weiner: Yeah, and it was up in Boston. They did it at the Huntington, then they’re reworking a bunch of it, and then it’s coming here.

Paste: But it’s the same team as in Boston?

Weiner: It’s a different cast, but Peter DuBois is still directing it.

Paste: And developmentally, at the Vineyard, readings and workshops are a big part of what you do. What’s coming up?

Weiner: We’re programming our spring reading series right now. We typically do a reading series in the spring and one in the fall, and then we do a larger lab for a playwright we want to devote extra time and resources to, to give them a chance with an audience, do the work, and see what it’s like on its feet. It’s very low-tech, but it has blocking and it’s a chance for them to stretch their dramaturgical muscles and see how it’s going. There’s no press, so they can do it in a safer environment.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-