Both Alien and Alienated, Angelyne Is a Barbie Girl Without a Barbie World

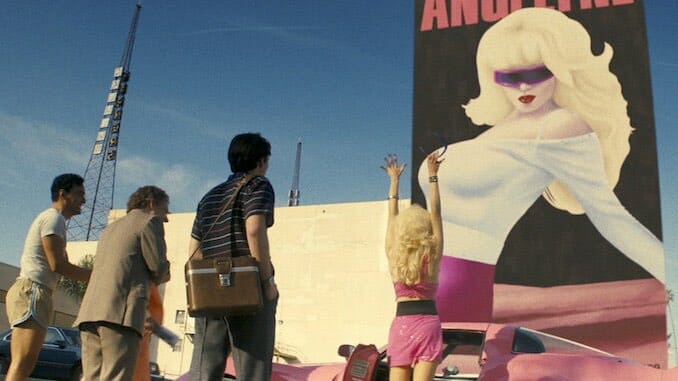

Photo Courtesy of Peacock

For a series intent on scrutinizing the launch of an LA local legend into notoriety, Angelyne’s first public major event spells out a major clue. As the frontwoman and lead singer of the short-lived band Baby Blue, Angelyne (Emmy Rossum) cartoonishly croons a two lyric song: “Kiss me LA // You know I’m getting off on you.” With her personal story so centrally wrapped up in the mythos of LA’s trappings—a glamorous place where make-believe triumphs over truth—the first line speaks for itself. But the second, gesturing at the sexuality with which Angelyne exuded from her billboards and over men, might be interpreted differently by viewers after watching Nancy Oliver’s miniseries. Getting off verbatim? Maybe, but it feels doubtful for Angelyne’s true motives within context. More convincingly, Angelyne appears invested in the project of getting away from anyone the “you” of her song could mean more than anything else.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-