This Season, Doctor Who Missed an Opportunity to Change Its Portrayal of Disability

Simon Ridgway/BBC America

I remember the first time Doctor Who portrayed my disability. It was a two-part episode in Season Four of the modern-era reboot, airing in 2008: “Silence in the Library,” followed by “Forest of the Dead.” They’re fan favorites, featuring the beloved Tenth Doctor (David Tennant), his zany companion, Donna Noble (Catherine Tate), and the first appearance of the mysterious River Song (Alex Kingston). Like all memorable episodes of Who, the two-parter has an intricate plot, full of high stakes and sacrifice. It also features a wedding—though brief and largely irrelevant, since it happens in a computer simulation. The wedding is Donna’s, and her groom is a man who stutters. Stuttering is a neurological speech disability, one I’ve carried since birth.

“Gorgeous,” Donna says, after meeting the man. “And can’t say a word. What am I gonna do with you?” I’ve already revealed what happens next: They get married. But a few scenes later, when Donna’s husband engages in a conversation that helps move the plot along, his stutter is noticeably, and conveniently, absent. He finds a letter on their doorstep and reads it aloud, without any effort or signs of stuttering: “Dear Donna, the world is wrong,” he reads. “Meet me at your usual play park, two o’clock tomorrow.”

This portrayal wouldn’t feel so inconsistent, if—at episode’s end—his stutter isn’t suddenly so debilitating that he can’t even manage to shout Donna’s name. Separated, the man searches for Donna, and Donna searches for him—but as soon as he spots her, he’s thwarted by his stutter. He attempts to say her name, over and over again: “D-D-D-D-D…” But it doesn’t matter. He’s transported from the library, still trying to shout her name. They never see each other again.

Watching this, the audience is supposed to think: Poor Donna, such bad luck with love. But this is not how it comes across to those of us with disabilities. To us, the message is clear: The inclusion of disability in Doctor Who is not an attempt at complex characterization. Instead, it’s an easy target for Donna’s jokes, and then a way to end the romantic arc in a tragic, sentimental way.

This is not an isolated example. In fact, the long-running sci-fi series has a history of misrepresenting the disabled. Though the modern-era reboot features characters of numerous ethnicities, citizenships, genders and sexualities, it’s still strangely tactless when portraying the disabled. Though the beloved series has been on air for more than fifty years all told, its physically disabled characters are often depicted as villains. There are many examples of this, but the foremost ones involve the Doctor’s most frequently recurring enemies, the Daleks and the Cybermen. These monsters were created by Davros (Julian Bleach) and John Lumic (Roger Lloyd Pack), respectively—both villains who are confined to wheelchairs. Both were overtly selfish, and eventually, completely evil—personality traits that seem to imply the disabled are “damaged” in more ways than one. That is, after all, a common stereotype of those who are disabled: That physical or neurological difficulties are somehow an indication of mental or emotional shortcomings. This simply isn’t true, but—in making two of its greatest villains handicap—Who does little to refute this misconception.

But these are examples from the show’s past. Surely things have changed?

Change seemed possible, especially after the fifth episode of the current season (“Oxygen”), in which the Twelfth Doctor (Peter Capaldi) tries to save his new companion, Bill Potts (Pearl Mackie), after her spacesuit malfunctions. As her face turns icy blue and she begins to pass out, the Doctor surrenders his helmet to her—and finds himself unprotected in the vacuum of space. The exposure leaves him blind, and though the Doctor pretends to be cured, he finally admits to Nardole (Matt Lucas), “I can’t look at anything ever again.” The camera goes dark as Capaldi delivers his last line: “I’m still blind.”

I was initially thrilled by this subplot. Not only did it offer an opportunity to explore one of the Doctor’s most interesting personality traits—his resourceful ingenuity—it also offered Who the chance to redeem its disappointing past portrayals of disability. Though the Doctor’s blindness could never erase previous problems with the series’ treatment of disability, crafting an accurate and compelling portrait of the Doctor with a disability would absolutely be a step in the right direction.

But—I’m sorry to say—the blindness subplot was ultimately unsuccessful.

For starters, we only receive one full episode of the Doctor blind. He’s blinded halfway through the fifth episode and cured by the seventh (“The Pyramid at the End of the World”). It would be difficult for any show to correctly depict a complex disability in a three-episode arc—let alone a sci-fi show that prioritizes weekly, interdimensional peril above all else. There simply isn’t enough time spent developing the Doctor’s blindness.

Not to mention the secrecy. The Doctor only willingly tells two people about his blindness: Nardole, who helps him keep it a secret, and Missy (Michelle Gomez), who’s trapped inside the vault and can’t tell anyone. In the sixth episode (“Extremist”), the Doctor leans against the vault and whispers, “They can’t know I’m blind, Missy. No one can know…” but he never explains why. Later in the same episode, Nardole finally confronts the Doctor. “Okay, so, you’re blind and you don’t want your enemies to know,” he says. “I get it. But why does it have to be a secret from Bill?” The Doctor mutters that he doesn’t like “being worried about,” but Nardole, in a particularly perceptive moment, interrupts him. “Shall I tell you the real reason?” he says. “The moment you tell Bill it becomes real, and then you might actually have to deal with it.”

The Doctor—in all his incarnations—is tightlipped and private, but his hesitation to reveal his blindness seems rooted more in shame than in the desire for privacy. Feeling ashamed by your newly acquired disability is an understandable, human emotion—but, as Who constantly reminds us, the Doctor isn’t human. In Season Seven, the Eleventh Doctor (Matt Smith) introduces himself to Clara (Jenna-Louise Coleman) by saying, “I’m the Doctor. I’m an alien from outer space. I’m a thousand years old.” Not to mention that the Doctor has traveled with his granddaughter, his wife and dozens of best friends, but has never told anyone “I love you,” even after they’ve told him—no, not even Rose Tyler (Billie Piper) received that honor. For a character who carries centuries of pain and bloodshed on his shoulders—I’ll never forget Season Five’s “The Vampires of Venice,” in which the villain of the week asks the Eleventh Doctor, “Can your conscience carry the weight of another dead race?”—it seems strange that our heroic Time Lord can’t accept the reality of his disability—especially when the disabled confront similar hardships every day. Even if I could suspend my disbelief, and accept that the Doctor can be overcome by shame from being blinded, this depiction is still harmful, because he never works through these feelings. He simply suppresses them—and hides behind his sonic sunglasses—until he’s eventually cured. If Who is willing to show the shame brought on by disability, it should also show the importance of seeking self-acceptance. Otherwise, the Doctor’s emotional arc suggests that being blind only produces shame.

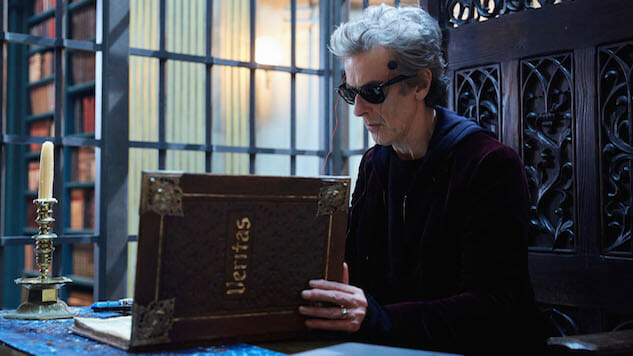

But where Who truly stumbles is the Doctor’s constant search for a cure. It begins as early as “Oxygen,” in which the Doctor waves off Bill’s concern. “It’s temporary,” he promises. “Once we get back to the Tardis, I’ve got something that’ll cure anything.” The cure, however, seems only to affect the color of his corneas—going from cloudy to clear, a purely cosmetic change. Then, the Doctor seeks a cure in “Extremist” after he’s asked to examine a mysterious text called the Veritas. To read the text, the Doctor seeks a momentary cure from a crude neurological device, claiming, “Either it’s going to temporarily fix my eyesight… or it’s going to burn up my brain.” He continues this monologue of glorified recklessness, saying, “I get a few minutes of proper eyesight, but I lose something. Maybe all my future regenerations will be blind. Maybe I won’t regenerate ever again. Maybe I’ll drop dead in twenty minutes.” This measure seems particularly ridiculous when—after wasting his moments of cured vision just trying to escape the Monks—the Doctor finally puts on headphones and has the Veritas read aloud to him instead. Seriously? You’re a brilliant, 2,000-year-old Time Lord. You couldn’t have thought of that solution first?

This season’s three-episode arc on disability is, at best, unsatisfying. And while it’s encouraging to see Who portray its lead character with a disability—considering the past, when the disabled were either villains or throwaway characters—the Doctor’s rise against adversity would’ve been much more triumphant if it had depicted more than just secrecy, shame and the constant search for a cure. Disability is difficult to live through and harder to portray accurately if you’re not, in fact, disabled—and that’s exactly how this depiction comes across, as a representation of disability written by abled-bodied writers who didn’t do any research. For example, if you read accounts written by those who are actually blind—such as Stephen Kuusisto’s acclaimed memoir, Planet of the Blind—shame is only one of many emotions he confronts as a blind man; Kuusisto even explores how disability often has a positive effect on his life and his senses. But these are epiphanies that took him decades to understand. Disability is complex, and cannot be fully tackled in three 45-minute episodes.

For a show like Who, which is known for being relatively progressive with regard to race, sexuality, gender, politics and religion, this portrayal of disability feels too quick and unsophisticated to meet the series’ usual standards. The fact that it’s possible to summarize this arc in less than twenty words—The Doctor saves Bill, is blinded, hides it, feels ashamed and is cured—should reveal how poorly conceived it is. When it comes to disability, we need to hold TV series to the same ethical and artistic standards of representation that we do other marginalized perspectives.

It’s unfortunate, but true: Doctor Who is still missing the mark when it comes to disability.

The season finale of Doctor Who airs Saturday, July 1 at 9 p.m. on BBC America.

Rachel Hoge is a southern writer, freelancer, and lover of all things TV. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming from the Washington Post, The Rumpus, HelloGiggles, Ravishly, and others. Lately, she’s been hard at work on her first nonfiction book. You can follow her on Twitter @hoge_rachel.