Why are the Making a Murderer Creators Being So Evasive About Ken Kratz’s Challenges?

A few notes before I begin.

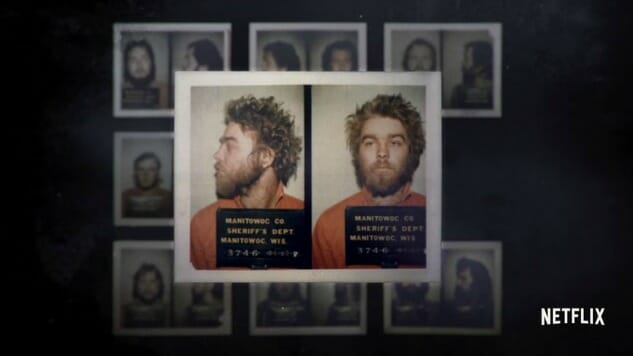

First: Major spoilers ahead for anyone who hasn’t seen the entirety of Netflix’s Making a Murderer, the compelling and well-made documentary about the murder of Teresa Halbach in Manitowoc County, Wisconsin, and the prosecution and subsequent conviction of Steven Avery.

Second: Please do not take this article as any kind of endorsement of Ken Kratz, whose behavior both during and after the trial of Steven Avery has fallen somewhere between “suspect” and “despicable.”

Third: Similarly, please do not take this article as a comment on Steven Avery’s guilt or innocence. It’s my opinion that filmmakers Laura Ricciardi and Moira Demos have, at the very least, exposed several (enraging) flaws in our judicial system.

That being said, there’s something more than a little off-putting about how Ricciardi and Demos have reacted to criticism of the way they presented their story—and what they left out—that I feel needs to be addressed. Making a Murderer obsessives will already know that prosecutor Ken Kratz has come out in severaloutlets claiming that they presented a false narrative that failed to include certain damning facts from the trial (and elsewhere) that pointed to Avery’s guilt. Namely:

*DNA from Steven Avery’s sweat that was found under the hood of Teresa Halbach’s car, and would have been difficult, if not impossible, to plant.

*Material from Halbach’s purse, including her phone and camera, were found burned in a barrel 20 feet from Avery’s door.

*Avery created a diagram of a torture chamber while in prison, and informed his fellow inmates of his intention to torture and kill women when he got out.

*A bullet with Halbach’s DNA, matched to Avery’s rifle, was found in his garage. The gun was confiscated on Nov. 5, 2005, and the bullet found in March 2006, which makes it difficult to think that it had been planted and left for over six months.

In short, Kratz thinks Demos and Ricciardi made a piece of slanted advocacy journalism, and purposefully omitted material that hurt their case in what anyone would consider a violation of journalism ethics. I want to reiterate that I am not endorsing any of Kratz’s arguments. Instead, if I have a thesis statement, it is this:

Journalists are responsible—absolutely responsible—for refuting fact-based criticism in the aftermath of their work. This is true even if those criticisms come from corrupt or disreputable sources, as they often will.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-