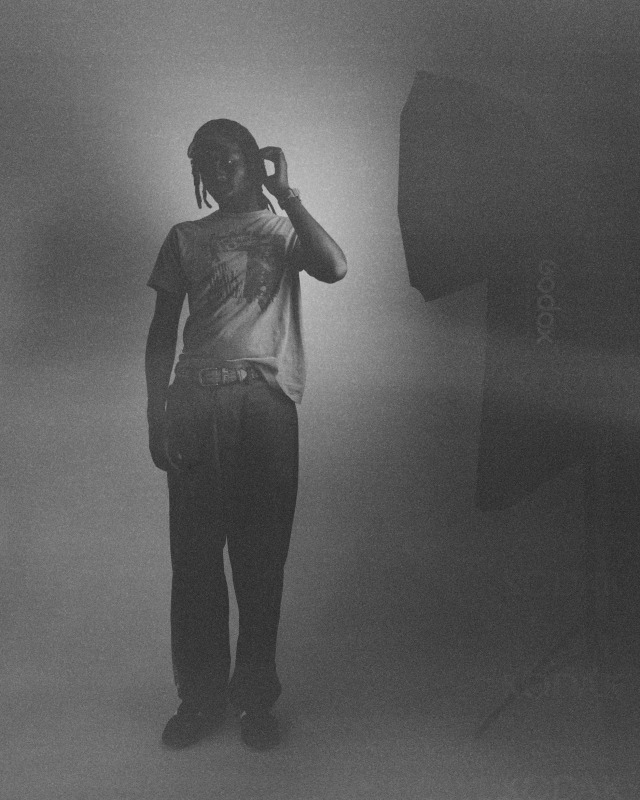

COVER STORY | Blood Orange, Between the Strings

Dev Hynes spoke with Paste about classical music giving freedom to Blood Orange, using samples to communicate with loved ones and old obsessions, curating voices outside of his own, and the grief that informed his new album, Essex Honey.

Photos by Vinca Petersen and Dev Hynes

After releasing his first Blood Orange album, Coastal Grooves, in 2011, Devonté Hynes co-wrote and co-produced what is, by my approximation, the best pop song released in my lifetime: Sky Ferreira’s “Everything Is Embarrassing.” After doting on a marriage of Brit-pop and emo-folk under the banner of Lightspeed Champion, his work on that one Ferreira track, along with his command on a slinky and evocative collision of dapped-up R&B, out-of-time New Wave, and cosmic electro-pop, put him in rooms with Solange, Lorde, Britney Spears, and Kylie Minogue—artists with “insane pop knowledge,” as he calls them. “It’s fun, because I don’t think that way—and I know I don’t think that way. And I’m okay with not thinking that way. I know what I can do, and I know what I can’t do, and I’m very sure in both of those arenas. It allows for me to have a lot of fun and have my mind blown. There’s a story and a lesson learned, every single time.”

But what feels even more improbable is that the hand Hynes has lent to pop’s current mecca is one of the least fascinating things about him. Sure, his recent CV includes playing guitar on “Favourite Daughter,” the best part of Lorde’s great new album Virgin, singing on Erika de Casier’s brilliant track “Twice,” and supplying drums to Vampire Weekend’s “Prep-School Gangsters.” But in another lifetime he was a teenaged guitarist in the post-hardcore band Test Icicles. Then he became a quiet mouthpiece for social justice, using photographs of trans women as album covers (in a way that reminds me, loosely, of what the Smiths did with their cover imagery 40 years ago) and putting trans women in his songs, pilling interludes with clips of spoken-word and Black film, and evoking the concrete poetry of Saul Williams and the melodic diversity of Mingus Ah Um.

In the last half-decade alone, as his side-quests have grown even more radical, he’s scored films like Queen & Slim and We Are Who We Are, collaborated with Philip Glass, and curated the music for Francesco Risso’s Marni fashion shows. And, after accepting an invitation from Hanif Abdurraqib, Hynes brought three classical works—Inheritance, the piano concerto Happenings (which he originally wrote for a sextet but later expanded for the BAM ensemble), and Fields—to the Brooklyn Academy of Music’s Opera House stage in 2022 and drafted Adam Tendler, the String Orchestra of Brooklyn, and Third Coast Percussion to perform them.

“When I am posing in that way, there is a freedom that I think I wasn’t necessarily always allowing myself when I was making Blood Orange music,” he admits. “In my head, I found a world that was ‘Blood Orange’ and would write more to my physical performance ability. In orchestration, it’s all your wildest ideas. You write them on the page, you fill out the notation, you add funny little symbols to it, and then it exists. Someone plays it. That process, to this day, is still mind-blowing to me. I can’t ever get over that that’s how that works. And I think that freedom definitely found its way into how I create Blood Orange music.”

But what seems to be the most impossible, I’d reckon, is that Dev Hynes is also batting 1.000 on his own studio albums, assembling what might be the most underrated run of solo material by any artist this century: Coastal Grooves, Cupid Deluxe, Freetown Sound, Negro Swan, and now, Essex Honey. The music—prismatic, fragile, and feminine pop strata—began in elegance, acting as sonar for like-minded eccentrics (Dirty Projectors, Caroline Polachek), living legends (Blondie’s Debbie Harry), and card-carrying members of this century’s pop pantheon (Carly Rae Jepsen, Nelly Furtado). And, thanks to a TikTok-motivated popularity boost, “Champagne Coast” recently went platinum.

WE CAN GLEAN FROM Hynes’ previous press revelations that growing up in London was not a particularly endearing experience. For every story he’s regaled about learning how to skateboard or playing football, there’s a tragedy of him—at an age not much older than the boy on the cover of Essex Honey, captured by Johny Pitts—getting spit on by schoolmates on the bus. As he put it in 2018, he was “a queer kid thinking of suicide.” Joy is subtle on Essex Honey but sorrow is abundant, as is nearness and leaving. Hynes, who is nearly 40, reaches towards gentleness in a way he didn’t on “Orlando” seven years ago, when he sang, “first kiss was the floor, but God it won’t make a difference if you don’t get up.”

“You try and find understanding, at least I did in my twenties and early thirties,” he says. “There was an energy—a confrontation—that I was working from and working with. And I think, now, it’s less about the fight and confrontation. It’s about going further back, deeper inside. The roots. Even when I was younger, I thought I was going into the roots. Now I realize that it runs deeper.” But there’s another side to it. Hynes says that, while Blood Orange wasn’t a pre-planned career, the older records captured him getting “a lot of things out of my system” in the moment. “It’s interesting now, when I look through [my work] and I can see a story within the albums,” he elaborates. “Stories end, so I think, ‘Well, what else is there to say?’ There’s always going to be something. I see the shape.”

When Hynes’ mother fell ill in late 2023, he cancelled a show with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra and went home to the grassy knolls and flat coast of Essex—to the “specificity” of his being born, growing up, and mortality. As the cold weather augmented his grief, and as hearing Sufjan Stevens’ “Fourth of July” on laptop speakers became a sobering sanctuary, he tended to her until she passed away in February, only to return to New York City and resume working on Essex Honey. He sang, “Nothing more to do but leave, following the corners of the room,” and “Another morning here without you.” He wrote, “Everything you knew has gone away,” and held pictures of the place he came from vividly within himself, processing the loss of a parent just as he had processed a loss of self on “By Ourselves” and “Smoke.” “Even if I didn’t need to be physically there to record, the idea of the literal place and, you could argue, the idea of the place, or the dream state of the place, were all very, very clear.”

Hynes once said, too, that “everyone should be aware of where things come from.” On Essex Honey, he’s applying that idea to himself and stripping metaphor from the chassis. The album is about growing up in England but written from the viewpoint of living in New York as an adult, where Hynes has resided since 2007. “If I was [in Essex], I don’t know if I could fully [make Essex Honey],” he says. “It’s the classic, ‘leave to write about the place’ thing.” There is a recording of Hynes’ sister and mother talking about the Beatles during their last Christmas together on “The Last of England,” but the street sounds you hear on “The Train” were recorded in New York. And that was intentional, meant to mimic a “memory with all the corners of it,” Hynes says. “It’s dreamlike, it’s hazy—it’s joy, sadness, grief, happiness. And the love of music and memories that are real, memories that are false. I’m trying to always capture those complexities.”

While in residence with BAM, Hynes used the Academy’s studio to dance and write piano improvisations. You can hear that in his arrangement of Caecilie Trier’s cello on “Thinking Clean” and “The Field,” or in the breakbeat-assisted piano contrasts cresting through “The Last of England,” or in “Mind Loaded,” which features actor Amandla Stenberg on violin. With those classical motifs feathered into schmaltzy electronica and drum ‘n’ bass, Essex Honey is effusive, vintage, and patchy, with beat switches, fade-aways, and a vocal syndicate not unlike the sensual coherence of Freetown Sound’s slinky, ‘80s-glorifying package. Periods of Essex Honey’s writing and recording, Hynes says, “shared an energy” with that record, because there’s a physicality present—you can “feel the hand and process,” so to speak, on a song like “Countryside.” On “Somewhere in Between,” I am reminded, above all, of the anachronistic, plinking synths in Arthur Russell’s “That’s Us/Wild Combination.” Like Weezer, his affinity for Malcolm McLaren’s “Madam Butterfly” is ever-present in his intentions, but Essex Honey’s best (subconscious) callback is to one of Hynes’ East England neighbors, Yazoo. Specifically, “Only You” emerges every time the synths in “Mind Loaded” wash over me.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-