Five Ways Your Amazing Movie Does Not Get Made

When people talk about “Hollywood Excess,” it’s usually in reference to explosion-heavy summer blockbusters, movie stars with sharks in their bathtubs, and cocaine. “Hollywood Excess” could also, of course, refer to the fact that the movie industry is the most gleefully inefficient machine in the history of capitalism. Millions of dollars are regularly thrown away on films no one watches or wanted. Equal amounts of money are spent optioning scripts that are never even made. Sometimes that money is spent just to prevent the movie from being made somewhere else. Of course, this lunatic process has produced some of our most beloved cultural artifacts, as well as a laundry list of amazing unrealized projects from our favorite filmmakers. So, for anyone who has ever wondered why an anticipated project suddenly evaporated, or why a no-brainer film version of a beloved book never even made it to the “looking for distribution” stage, or even why their friend’s passion project falters and fails, this list may provide an answer.

1. You Are Way Ahead of Your Time

If you want to increase your chances of being lionized by movie nerds forever, the best way to have your movie not get made is to have a concept so cool that producers eventually assume it could not possibly work. The movie doesn’t get made, the concept abstractly succeeds in the mind’s eye of the fans, and you walk away looking like a tortured genius.

The most famous example of this is Alejandro Jodorowsky’s unsuccessful attempt to adapt Frank Herbert’s Dune—a book he had not read—into a film in the mid-1970s. (This is arguably the most famous and most painfully unmade film, and one we will return to many times throughout this list). Jodorowsky’s vision was so sprawling and impressive that even though the movie was never made, its concepts alone served as a blueprint for the next quarter-century of big budget sci-fi films. Jodorowsky hired Dan O’Bannon (Star Wars), Moebius (Tron), and H.R. Giger (Alien) to design the film, and approached various prog rock groups to compose music for the film’s different planets. The whole thing was so trippy and bizarre that it eventually collapsed under its own weight, but not before changing the landscape of science fiction in the process.

Jodorowsky wasn’t the only filmmaker to create concepts that seemed absurd at the time, but, retrospectively, would have been incredible. In 1991, James Cameron submitted a profanity-ridden Spider-Man “scriptment” that would have featured Peter Parker and Mary Jane Watson having sex on the Brooklyn Bridge. Cameron borrowed so many elements from equally insane previous drafts (including a Kafkaesque nightmare sequence) that impending litigation prevented the film’s production. David Fincher labored for years to produce a remake of the 1981 adult animated movie Heavy Metal, based on the long-running erotic science fiction magazine, assembling a murderer’s row of collaborators before the film was deemed too risqué for audiences.

Alien 3 eventually disappointed audiences and hardcore fans everywhere, but the initial scripts written by William Gibson (Neuromancer) and Vincent Ward could have made 3 the best entry in the series. Gibson’s script involved the surviving crew of the Sulaco drifting into territory controlled by space Marxists, but even that paled in comparison to Ward’s vision of a wooden planet inhabited by Luddite monks, which, after Ripley and Co. crash-land, becomes the setting of a religious-horror adventure featuring stunning action set-pieces including a chase through a wooden, vertical library shaft. Unfortunately, Jon Landau felt it was too “artsy-fartsy” and went in a different direction, but if the past few years have proven anything, it’s that artsy-fartsy sci-fi (Moon, District 9 and Arrival) wins in the end.

We could go on and on and on, from David Lynch’s Ronnie Rocket (in which a detective fights electricity-welding “Donut Men” in a second dimension), to Hitchcock’s attempt to match the French in terms of formal invention in Kleidoscope, to Roger Ebert’s script for a Beatles-esque comedy film featuring the Sex Pistols. The point is that if you have a really unusual and amazing concept, be prepared to wait twenty years to make it.

2. Your Budget Is Too Big

This is the most common pitfall for potentially fantastic films. Either special effects have not caught up to your concepts, or else you just have no idea how to spend money, but chances are if your movie isn’t getting made, it might be time to scale things back a bit. Jodorwosky did not seem to understand the concept of money while making Dune, and when Herbert traveled to visit him in 1972, he found that Jodorowsky had spent two million dollars of a ten million dollar budget developing a fourteen-hour script without shooting a single frame.

Francis Ford Coppola had reportedly shot thirty hours of footage for a massive sci-fi undertaking called Megalopolis, which pits a corrupt mayor against an idealistic architect with New York City as their battlefield. However, the 212-page script contained so much, so many subplots, and so many things that it was deemed too huge to actually complete. The events of 9/11 were the final nail in the coffin for Coppola’s dream. New York was no longer suitable for Megalopolis.

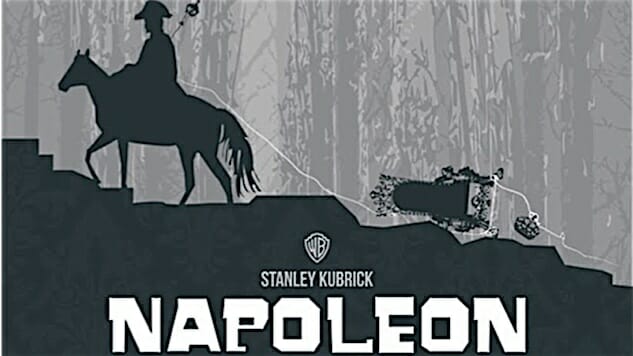

Location filming and its prohibitive costs also sunk Stanley Kubrick’s unrealized masterpiece, a biographical film about Napoleon Bonaparte which he felt was to be “the best movie ever made.” Kubrick even went as far as to enlist the Romanian army, planning to shoot some of the film’s massive battle sequences with over 50,000 Romanian soldiers on location. Investors eventually balked at the price-tag, and the project was dropped.

More recently, Guillermo Del Toro, a man we should trust with our very lives, attempted to adapt H.P. Lovecraft’s novella At the Mountains of Madness, an ideal pairing that unfortunately made studio heads nervous; the cost would be comparatively huge for a movie that couldn’t possibly have either a love story or a happy ending. It was eventually stalled due to similarities with Prometheus, so … the joke’s on us.

Of course, your budget might not be a problem when you start. Consider Terry Gilliam, who has spent most of his career at this point (eight tries in nineteen years) attempting to film The Man Who Killed Don Quixote, a loose adaptation of Cervantes’ novel. Though Gilliam miraculously secured European funding and began to film in Spain in 2000, the production was plagued by flash floods, creating insurance difficulties that have made securing additional funds to re-try the film impossible over the years. Gilliam insists that he “will be dead before the film is.” But sometimes the money just isn’t there. We’ll always have the excellent “making of” documentary Lost in La Mancha, at least.

3. People Keep Dying

Death is always a bummer. But when death prevents a potentially great movie from being made, it stings even more. (Not really. But sometimes.) Take the many attempts to adapt John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces, some of which date back to the novel’s publication itself. In 1982, Harold Ramis planned an adaptation which would star John Belushi as Ignatius. Belushi, of course, died of an overdose later that same year. The Ramis production later tapped both John Candy and Chris Farley for the film, with similar results. The Huntington Theatre Company eventually produced an adaptation in 2015 starring Nick Offerman. We can only hope he continues to survive.

And that’s only the most famous example. Only forty minutes of Something’s Got To Give were filmed before Marilyn Monroe’s death in 1962 (including a scene that would have made Monroe the first major film star to appear in a Hollywood release in the nude). Chico Marx died before Billy Wilder, of all people, could film the Marx Brother’s comeback film, A Day at the United Nations.

The death of the filmmakers themselves have prevented the completion of projects — some of which were lifelong endeavors. Orson Welles labored for thirty years on his own adaptation of Don Quixote, shooting footage as early as 1955 and tinkering with it as late as 1985, the year he died. A version edited by his collaborator, Jesus Franco, was released in 1992, but can hardly be considered official. Poor Andrei Tarkovsky (Solaris) spent his entire life pushing the Russian government to approve an adaptation of Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot, only to die a few years after signing a contract to write the script. Sergio Leone read The 900 Days: The Siege of Leningrad while filming Once Upon a Time in America, and spent the rest of his life planning a depiction of the siege that would have been one of the most epic war films of all time. He had recruited Robert DeNiro and raised 100 million dollars by 1989, but died of a heart attack two days before he was supposed to sign his contract. David Lean intended to film an adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s Nostromo (yes, that is the name of the ship in Alien) that would have starred Marlon Brando, Paul Scofield, Anthony Quinn and Peter O’Toole, but died a few weeks before filming began.

Even the death of a fictional character can prevent a movie from being made. When the film adaptation of L.A. Confidential turned out to be a big hit, development began on an adaptation of White Jazz, another Elroy novel that shares several characters with L.A. Confidential. However, two separate attempts to film the novel fell through, in part because a key character had been killed off in Curtis Hanson’s film version of L.A. Confidential. They ended up making White Jazz anyway, and it’s called La La Land! Hey-O! Zing! Roasted!

4. There Is Bona Fide “Crazy” Involved

Photo by Vince Bucci/Getty

A certain amount of ego is necessary in getting any artistic endeavor on its feet. If everyone was nice and reasonable all the time, nothing would ever get done.

That doesn’t necessarily excuse the behavior of Jon Peters, the self-proclaimed “Donald Trump of Hollywood,” who bought the rights to the Superman film franchise from Warner Bros. and intended to produce Superman Reborn/Superman Lives. Kevin Smith was hired to write the film, but (as detailed in an incredible anecdote on one of his Q&A DVDs) had to deal with Peters’ increasingly bizarre requests. Apparently, Smith was supposed to write a Superman movie where Superman does not fly, does not wear his “faggy” (Peters’ words) suit, and must fight a giant spider in the third act. Peters also insisted that Brainiac (Smith’s choice for the film’s villain) must fight two polar bears. Years and years later, Christopher Nolan would ban Peters from the set of Man of Steel (where Nolan was a producer). However, a close up of a lone polar bear was included in the final film. So Peters eventually got his way.

On the subject of ill-fated genre adaptations, Alejandro Jodorowsky wasn’t even the craziest person involved in Dune. He reportedly approached Salvador Dali to play Shaddam IV, the Mad Padishah Emperor. Dali agreed, on the condition that the Emperor’s throne room be outfitted with a flaming giraffe, and that he be the highest paid actor in Hollywood. Jodorowsky, for some reason, agreed, but arranged things so that Dali would have a fraction of his original screen time, making him the highest paid actor-per-minute in Hollywood. Dali brought his brand of crazy to other projects, too. Apparently he was very excited about a potential collaboration with the Marx Brothers, which he wanted to call Giraffes on Horseback Salad. No word on what ever happened there.

Or, you could theoretically complete a film and just choose never to release it. That’s what happened with Jerry Lewis, whose The Day the Clown Cried—about a man entertaining children in a concentration camp (no, not that one)—was supposed to be his defining work. Apparently it turned out so embarrassingly bad that Lewis sealed it away forever—the single reasonable act by a man who ate nothing but grapefruit for six weeks in order lose enough weight to play a clown named Doork who leads a bunch of kids, Pied Piper-style, into a gas chamber.

5. You Get Bored and Are a Genius

Photo by Kevin Winter/Getty

Ultimately, most great movies don’t get made because the geniuses behind them get super bored and something else comes up. William Goldman and Stephen Sondheim wrote several drafts/songs, respectively, for a musical film called Singing Out Loud before director Rob Reiner lost interest and everyone just wandered off in different directions.

Or, once you’re as successful as Quentin Tarantino, you can basically announce any movie you want and start working on it, or not, and no one will really bother you about it after that. Since Tarantino plans to retire after his tenth movie (that’s two movies from now), we’re unlikely to see most of the movies he’s expressed interest in making, but that does not mean the litany of Tarantino’s unrealized projects does not sound pretty amazing. The Vega Brothers/Double V Vega would have reunited brothers Vic Vega (Michael Madsen’s “Mr. Blonde” in Resovoir Dogs) and Vincent Vega (John Travolta’s character from Pulp Fiction) for some kind of mayhem. A hypothetical third Kill Bill film would have picked up ten years after the original installments, and featured the daughters of Vernita Green and Sophie Fatale avenging their mothers’ death at the Bride’s hands. We’ve also heard tell of a science fiction film, a new adaptation of Bret Easton Ellis’ novel Less Than Zero, and movie called Killer Crow, about a group of black soldiers going rogue in World War II, which would have completed a thematic Inglorious Basterds–Django Unchained trilogy by combining the plots of both. Turns out instead of all of these we’re getting a Bonnie and Clyde tribute and an untitled nonfiction film about the year 1970. Oh well.

But no one—no one—plans movies that they eventually forget about better than Joel and Ethan Coen. Not that the Coens haven’t given us plenty of great movies already, but we have been promised adaptations of James Dickey’s To the White Sea, Michael Chabon’s The Yiddish Policemen’s Union, Ross Macdonald’s Black Money, a Wired article about the Dark Web, plus a short film anthology about a dusty library book called The Contemplations, a cold war comedy called 62 Skidoo, a musical comedy about opera that’s not technically a musical, a roman sword and sandals drama, a sequel to Barton Fink set in the ’60s called Old Fink, and a slew of TV projects. Whew.

They seem pretty chill about it all, too, with Michael Chabon stating that the Coens wrote a full draft of a Yiddish Policemen’s Union script and “then seemed to move on.” I guess when you’re the Coen Brothers, your life consists mostly of banging out scripts based on acclaimed novels and letting episodes of Fargo stack up on your DVR. If, however, they make sure none of their ideas are too cool, their budgets are nice and small, John Turturro is alive, and Jon Peters is not involved, we may yet see an Old Fink in our lifetime. At least, we can hope.