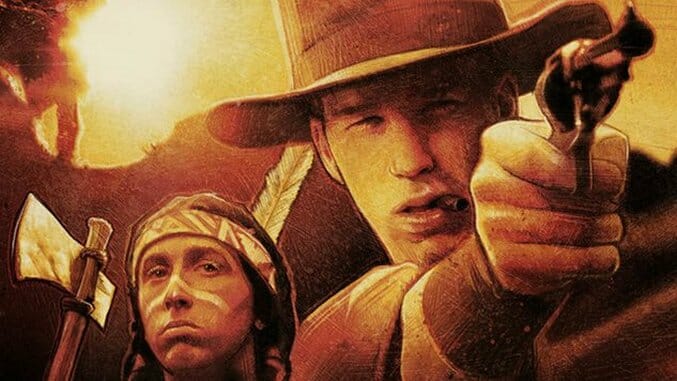

Square One: Edgar Wright’s A Fistful of Fingers (1995)

Whenever a filmmaker of note premieres a new film, it’s a good time to revisit that director’s first film to gauge how far they’ve come as an artist. With Baby Driver hitting theaters on June 28th, we take a look back at Edgar Wright’s A Fistful of Fingers.

Edgar Wright has built his career on pastiche—his back catalogue contains the DNA of everything from George Romero’s zombie pictures to The Legend of Zelda to Invasion of the Body Snatchers—so it makes sense that his debut operates within one of the most enduring genres of all time. A spoof Western titled A Fistful of Fingers, the movie is a remake of an undistributed picture (of the same name) Wright made while still in school, and though the reboot has not shaken the student-film look (the characters’ clothes are clearly costumes, and the actors look to be no more than in their early twenties), it is witty and relentless enough to dodge most accusations of amateurism. In fact, as the film progresses, its cheapness of production quickly becomes an asset, enhancing the impression of performative, self-conscious genre burlesque of the sort that wouldn’t feel out of place in the oeuvre of Mel Brooks.

A Fistful of Fingers resembles its eponym—Sergio Leone’s Spaghetti Western A Fistful of Dollars—not so much in overall plot as in an abundance of isolated elements, the most obvious of which is The Man With No Name, here played by Graham Low with the same leery squint, taut-mouthed scowl and patterned shawl that made Clint Eastwood into a genre icon. At the start of the film, Low’s “No-Name” is chasing after an outlaw named “The Squint” (Oli van der Vijverin) in the hopes of collecting the bounty on the criminal’s head. His journey brings him to a village, and his cold reception by the townspeople is pulled straight from the analogous scene in the Leone film.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-