University Students Recreate 5,000-Year-Old Beer

Long before bearded hipsters started experimenting with brewing cinnamon IPAs in their parents’ garages, ancient civilizations had figured out the art of homebrewing. As far back as 5,000 years ago, budding brewers in northern China were raising pints in a primitive, subterranean brewery. Now, thanks to fancy, science things like “phytolith morphometrics,” researchers have figured out how to recreate the ancient brew.

Li Liu, a professor in Chinese archaeology at Stanford University, was part of a research team that deciphered the ingredients of one of the world’s oldest beers by studying the inner walls of pottery vessels found at an excavated site in Shaanxi province.

After uncovering the recipe, she did what any good teacher would: she made her students brew it.

As a final project for one of Liu’s courses, Stanford students were required to brew a batch of ancient tipple using a recipe that dates back 5,000 years. Beer was a little different back then. Forget the enticing hue and bubbly perfection of modern craft beer, this old-school booze looked more like porridge, and it had to be sucked through a straw to avoid the chunky bits.

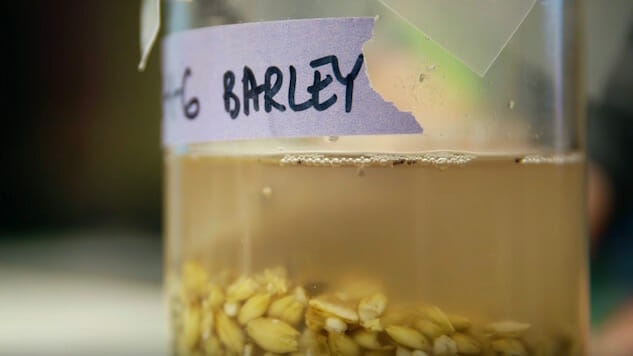

However, much like modern beer, the core ingredient in the Neolithic sludge was cereal grains, including millet and barley. Instead of hops, the pioneering Chinese brewers used Job’s tears (a type of grass found in Asia), as well as traces of yam and lily root parts for added flavor.

The brewing process hasn’t really changed much in 5,000 years, so the students stuck to the basics when recreating the old Chinese happy-sauce. In a process called “malting,” the grains were submerged in water until they began to sprout. After malting, the grains were milled (or crushed) before being placed back in water and heated to a specific temperature to draw out the fermentable sugars. Next, the mixture was cooled and yeast was added to work its magic. A week or two later and the ancient brew was ready for gulping. Straw, anyone?

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-