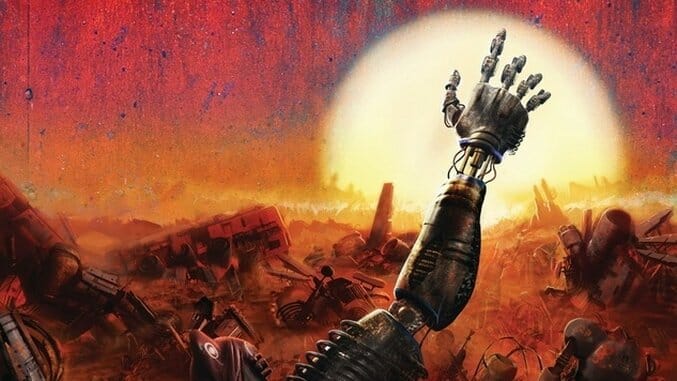

C. Robert Cargill Talks a Post-Human World Run by Robots in Sea of Rust

There are no human characters in C. Robert Cargill’s latest novel, Sea of Rust. An intriguing subversion of the robot-apocalypse genre, the book takes place years after human beings have been exterminated. Instead, bots and AIs take center stage as they struggle to survive the new, foreboding world they’ve built for themselves.

Cargill has come a long way since his days as an acerbic Ain’t It Cool News film reviewer in the wild west days of the early blogosphere. His profile has steadily written since hooking up with writer/director Scott Derrickson in 2011, which resulted in the well-received horror-thriller Sinister. Since then, he’s written two novels, Dreams & Shadows and Queen of Dark Things, and contributed to some major Hollywood properties, like Marvel Studios’ Doctor Strange directed by Derrickson.

Paste called Cargill at his home in Austin, Texas, to talk about writing scripts vs. novels, fully automated luxury gay space communism, and Sea of Rust.

(The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

Paste: Over the past couple of years, you’ve been making a name for yourself in the screenwriting world. What is it about the novel form that keeps you coming back to writing prose? What do you enjoy about a novel that you can’t really accomplish with a screenplay?

Cargill: I guess the biggest thing is that the audiences are different. And the audience for books will be patient and willing to indulge the writer. As long as you entertain them, as long as you keep the story going, they’ll accept oddities or lulls or sidebars and the like.

You look at the type of stuff that George [R.R.] Martin does in his books versus what they do in Game of Thrones, and there’re whole parts of what makes the books the books that you just can’t translate to the screen. The books have this deep, rich love of food and talk about the various feasts they have. That you don’t really get in the show. And so, this great word exercise if you will, this feast of words, isn’t something that you really can get in cinema, so there’s a lot of stuff that I just can’t do.

And also at the same time, you get to play around with a lot of ideas that Hollywood would never let fly until they saw work some other way. If I went into a studio and pitched Sea of Rust, a lot of them would say, “That sounds great, but you just need a human being. If you don’t have a human being, audiences aren’t gonna accept it, so can you have them find a tribe of humans, or the last surviving human hanging out with robots?” And that’s not the story I wanted to tell; we’ve seen variations of that story so many times.

Paste: That’s one of the things I found interesting reading Sea of Rust, because that’s just naturally where you assume the story is going when it starts. I imagine it was kind of fun to subvert people’s expectations like that.

Paste: That’s one of the things I found interesting reading Sea of Rust, because that’s just naturally where you assume the story is going when it starts. I imagine it was kind of fun to subvert people’s expectations like that.

Cargill: That was the whole point. Before anyone else read the book, I thought I was gonna have to do some kind of public thing or word things just right so I can be like “No guys, really, there’re no people.” And to my amazement, people have been super excited about that fact. They lay it out up front, they’re like “Oh my God, there legitimately are no people. We’re just gone. I kept thinking that it was gonna show up and they never… This guy is serious. They don’t come back. They’re not here.”

And that’s what’s great about the novel form, it allows you to experiment. Since it doesn’t require any money to write a novel, you essentially get to experiment and do the things that no one else thinks can work. And that’s what I think is really great about it.

Paste: It’s not like there’s a studio putting up a hundred million dollars and they’re expecting some big windfall to make back their investment.

Cargill: Exactly. And you get to do stuff like in my previous two books, how I interspersed the chapters with these interstitial chapters that were told like they were written from guide book entries. And to where I was able to go deep into the history of these pieces of folklore and seed that into the story without trying to force it into the actual narrative. You can’t do that in a movie. And so I do love playing with the form a lot; that’s one of the things I really love about writing novels.

Paste: In Sea of Rust, there is a section where you talk about the beginning of the conflict between humans and robots. And how one of the main AIs determines that one of the issues driving humans toward destruction is that we can’t decide to go on one path or another towards pure capitalism or pure socialism. Is that a problem that you’ve identified and think is causing conflict?

Cargill: Yes and no. I mean, the big problem with AI is going to be that. I don’t think overwhelmingly that is the big debate we have. But the reason that the robot mentions that is that the robot is actually fucking with people, because it knows that human beings love to swing at that pitch. If you wanna get republicans and democrats yelling at each other, you just bring up socialised health care and just watch them tear each other apart. Good friends will sit there and get into screaming matches over it, and so that’s part of what the robot was doing.

But at the same time when it comes to AI, that’s a very real problem that we have to figure out. Part of what caused the downfall in the book is robot labor destroys jobs, and destroying jobs undercuts the economy, because, as free market capitalists like to say, the market decides things. Well, the market is people with money. And if there aren’t enough people with money, then there is no market to decide anything. And so with things like AI, you either need to go full on capitalism (which involves certain ownership issues and certain things that robots can and can’t do) or you need to get into the idea of socialising things like universal basic income, as many people are experimenting with, to accomodate for the fact that these jobs don’t exist anymore.

But ultimately, I personally think that all roads lead to socialism in terms of this. I feel like this phrase that’s being tossed around now, “late stage capitalism,” is actually right on the money. That we are about to see the end of the pure libertarian capitalism days, and that we are going to slowly approach more and more of a Star Trek-like future.

Paste: Fully automated luxury gay space communism.

Cargill: Yeah! Exactly. The protestant work ethic is dead. There was a point in time in history where the protestant work ethic was essential, because me going out to work for eight or 10 hours actually substantively created something for society. It’s like, “I have built a table” or “I have made tools” or “I have grown corn” or “I have raised horses.” I have done something that society now has as a result of my labour.

The bulk of labor as we’re starting to develop it is services labor, but not trained services. It’s a human body here to restock shelves. Most of the people who work at Wal-Mart, which is the United States’ largest employer, their sole job is to keep shelves stocked so people can buy things. And most of the other jobs are then ringing people up for buying things. And once robots can do all of that, then you now have 1.3 million people who don’t have jobs. And what do you do with them when their labour isn’t creating anything? When those people are not employed, we’re not gonna notice that “Oh, society got worse.” Society doesn’t have these people creating this stuff anymore, cause they’re not creating.

So, as you said, luxury gay space communism. It’s like, what else is the point of society and all of this automated labor if not to create a more comfortable, better society for us? The question then becomes, what do we do with that spare time? Because human beings were not designed to luxuriate 24/7. So, it’s gonna be very interesting to see how we psychologically deal with these things that are coming our way. [In Sea of Rust], because there is that struggle, the rich people grasping onto that last bit of “I have more than you” is ultimately what brings down their world.

Paste: It’s certainly an interesting time to be alive, since we’re gonna see all these things that we’ve been reading about in William Gibson novels and seeing in James Cameron movies for years and years. Bringing it back to Sea of Rust, you’ve created a unique universe within a really well-tread genre. Do you have any intention of returning to it, or maybe using it as a basis to tell more stories?

Cargill: I wrote it as a one-shot, but I did build a world that could be built upon; there are definitely tons more stories to tell in it. It really all comes down to how much people enjoy it. If there’s a large audience for it that’s like, “Yes, we absolutely want more of this,” then I’m definitely keen to dive back in and see what other gold can be mined from it. And that’s really what it all comes down to; there can be more stories in it, I just didn’t intend for it to be that way.

But then again, that’s how Dreams and Shadows was written as well. Dreams and Shadows was intended as a standalone, but [the publisher] bought it and said, “We would really like a second one.” And I was like, “Yeah, sure. I can come up with more stories in this world.” And there’s a third final one of that coming that I’m gonna sit down and write later this year. So the hope is that people like it enough that they ask me for it, and if enough people do like it enough that they ask me for it, then yeah, of course I think there’s more stories there.

Paste: Well, I wish you all the best with it.

Cargill: Thanks!