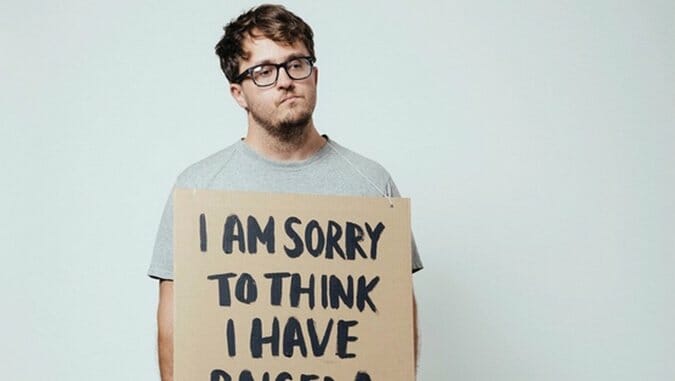

I Am Sorry to Think I Have Raised a Timid Son by Kent Russell

Kent Russell, or in the very least, the Kent Russell of I Am Sorry to Think I Have Raised a Timid Son, is a Conscientious Man. Well, he is in the process of being a Conscientious Man, which is all the Conscientious Man can hope to be. Regardless of whatever threat he is staring down, Russell is keenly aware that something is amiss in his very soul and loins. I Am Sorry to Think I Have Raised a Timid Son aims to figure out what.

The book is a non-fiction mutt, equal parts memoirs and essays and journalism. One learns of young Russell’s penchant for injury, his thoughts on hockey and how it feels to be a Juggalo, and each seems achingly important. He shatters masculinity, blasts it through a prism and decides to follow the weirdest, darkest wavelengths to their very ends. He parses his own military heritage, attempts to rectify his place in a family of warriors, then falls through the looking glass profiling a childhood friend who actually became a son of Mars. He attempts to make his dogged horrors physical—remember, real men prefer a corporeal opponent, something they can mash, bite—then kneels at the feet of Tom Savini, Father of Beasts, King Butcher.

In Fond Du Lac, Wis., Russell introduces us to Tim Friede, who has taken man’s desire for inviolability to its intoxicating extreme, purging himself of even the most recognized and acknowledged of flaws: our susceptibility to snake venom. Friede is a practitioner of mithridatism, named for the Poison King, Mithradates VI, who immunized himself so effectively against the various foul defenses of nature that even Rome’s best poisoners could not make him sick. Friede voluntarily envenomates himself—when Russell sees him, via snake-and-fang—to inoculate against the serpents: an African water cobra, even a black mamba does not kill Friede. When Russell leaves him, he is hunched pitifully over a space heater alone, limbs still rigid.

In John Brophy, a brutal enforcer who stalks hockey lore like Polyphemus, Russell explores ritualized male violence. Russell is enraptured by the goon, the man throwing hands in the old fashioned way, fighting, if not for his very life than his livelihood (which, often enough for these men, ended up being one and the same); yet he also understands the fatalistic call of the brute past, the suicidal tendency to think those who came before were forever tougher, forever stronger, forever better men. Such is the fate of tough men. The ancient Greeks knew it, killing all of their heroes before they could become ghouls.

![]()

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-