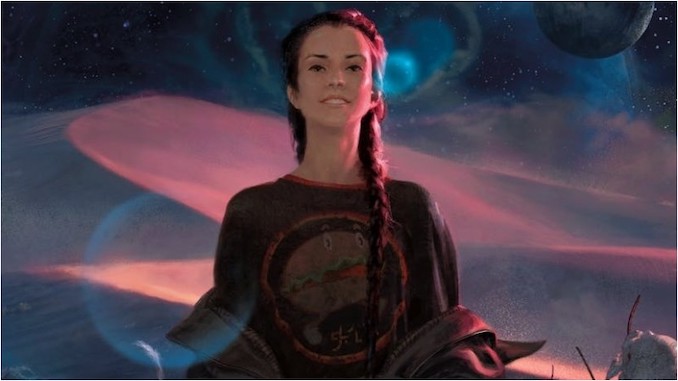

Nona the Ninth: Tamsyn Muir’s Locked Tomb Series Remains Defiantly Weird and Strangely Beautiful

Tamsyn Muir’s Locked Tomb series actively resists easy explanation, a story of impossible loss, love, and grief set in a far-flung universe where necromancers reign in the Nine Houses built on the bones of murdered worlds. Part fantasy, part space opera, and part apocalyptic nightmare, the story follows the swashbuckling adventures of bone mages and flesh adepts, cavaliers, skeleton armies, petty bureaucrats, and even God himself. Muir’s biting, hilarious prose is full of dark subject matter (violent death, creeping body horror, and various bits of effluvia and gore are commonplace) but tons of heart, deftly exploring issues of identity, belonging, love, and family.

It’s truly unlike anything else in science fiction and fantasy, and the best way I can explain its appeal to you is simply to tell you to go read it and find out for yourselves. (It’s worth it, I promise.)

But since the Locked Tomb series as a whole frequently defies description, it shouldn’t shock anyone that its latest installment, Nona the Ninth, does too. A book that wasn’t even supposed to exist in the first place—the bones of this story were originally slated for the first act of the upcoming series finale Alecto the Ninth—Nona is the series’ most personal and human. To be fair, it also contains just as much violence and cruelty as its predecessors. Characters die, get resurrected, and swap bodies just as easily as ever. But where Gideon the Ninth ended in tragedy and Harrow the Ninth was a study in grief, Nona the Ninth feels like something altogether different: A story about life, and maybe even a little bit about hope.

Set over five days during the countdown to an apocalyptic event, Nona the Ninth’s story is initially deceptively mundane. Though she’s only six months old (in a nineteen-year-old body she knows doesn’t belong to her), Nona is a being of simple pleasures. She loves her job at a local school, and the pack of streetwise kids she’s befriended there. She loves dogs and the ragtag group of three adults (who share two bodies) that have become her family. And while she may live in a war-torn city full of poverty and violence, all she wants is a birthday party at the beach. (Even if the water is such that no one should probably do any swimming.)

Nona makes for a delightful protagonist whose innocent, childlike way of navigating the world feels like a breath of fresh air after two books worth of secrets, betrayals, and ulterior motives. But at the edges of her life, we see hints that things are not as idyllic as our heroine believes. There’s a giant blue sphere in the sky, and it might be making everyone sick. The resettlement camps are growing restless and hard to control. People are burned to death if they’re suspected to be zombies. And everyone seems to think Nona’s true identity holds the key to either saving or damning the empire, no matter how she feels about the subject.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-