The Greatest of Marlys is Lynda Barry at Her Greatest

Writer/Artist: Lynda Barry

Publisher: Drawn & Quarterly

Release Date: August 16, 2016

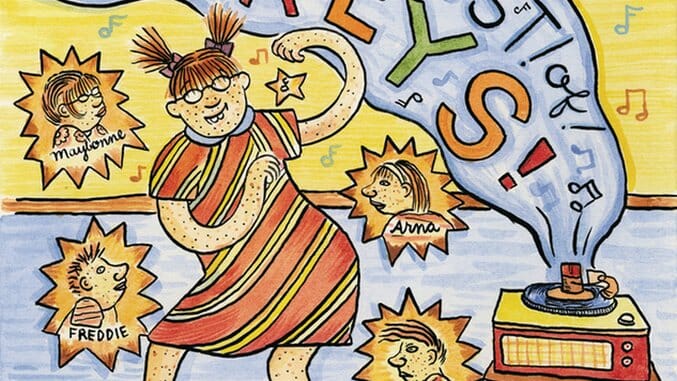

The Greatest of Marlys reintroduces a collection of Lynda Barry’s four-panel strips, which ran in alternative newspapers across the country from roughly 1980 to recently under the Ernie Pook’s Comeek moniker (she still makes work, but the newspaper business isn’t faring quite as well). Barry has remained reliably prolific for decades, and it wouldn’t be surprising if she gets her “complete works” in print someday, but for now they’re available in bits here and bits there. These specific 224 pages collect selections from the comic published from 1986—when she introduced the characters of Marlys, Arna, Arnold, Freddie and Maybonne—to 2000. If you grew up reading Barry’s output, sandwiched between copious local event listings, ads for sexy telephone lines and angry letters focused on city minutiae, opening this book will jolt you back to those days.

The Greatest of Marlys reintroduces a collection of Lynda Barry’s four-panel strips, which ran in alternative newspapers across the country from roughly 1980 to recently under the Ernie Pook’s Comeek moniker (she still makes work, but the newspaper business isn’t faring quite as well). Barry has remained reliably prolific for decades, and it wouldn’t be surprising if she gets her “complete works” in print someday, but for now they’re available in bits here and bits there. These specific 224 pages collect selections from the comic published from 1986—when she introduced the characters of Marlys, Arna, Arnold, Freddie and Maybonne—to 2000. If you grew up reading Barry’s output, sandwiched between copious local event listings, ads for sexy telephone lines and angry letters focused on city minutiae, opening this book will jolt you back to those days.

Dame Darcy’s Meat Cake Bible, published by Fantagraphics in July, makes for an interesting comparison. Both artists exercise a compulsive need to fill up the page with words and images, as well as border decorations and pattern, and both have a love of outsider culture. Recurring characters pop up in both works, and both present a world largely occupied by women. However, Barry creates emotional involvement with her characters by breadcrumbing an ongoing narrative. One piece of her work is nothing. A whole bunch of pieces constitute a nourishing meal.

The Greatest of Marlys Interior Art by Lynda Barry

Barry displays insight into the childhood mindset like almost no one else—in any medium, not just comics. Her work is a bubbling font of immediate, sensory experience: the joy of late summer evenings with the radio on, the itch of lying in the grass, the brainless pleasure of acting like a goofball. Marlys is both young enough and old enough to be interesting. Her dreams are fresh and uncrushable, and the contrasts Barry draws with her older sister, Maybonne, and her single mother induce a warm sadness in the reader. Third grade is a golden era. You can read. You exert a little independence. You have differentiated yourself from your parents. But the complications of hormones have yet to enter the picture, and you’re still free to behave as goobery as you want.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-