How Canadian Booze Supplied America’s Prohibition-Era Thirst

Photos via Shutterstock, Unsplash (Laure Noverraz)

This piece is part of a series of essays on alcohol history. You can read more here.

The grand irony of Prohibition in the U.S. is that although it did indeed succeed in curtailing drinking among many of the law abiding, it arguably made obtaining a drink easier than ever for many other Americans. The period between 1920-1933 devastated the country’s commercial beverage alcohol industry, but simultaneously illustrated that we didn’t really need that industry to exist in order to keep getting loaded–not when so many other manufacturers, bootleggers and enterprising homebrewers were waiting in the wings to supply the country’s thirst. From every direction, the booze poured in through the flimsy dotted line that was meant to represent America’s supposedly dry borders. Turns out that prohibiting alcohol production isn’t quite enough, when none of your neighbors are joining you in the grand endeavor.

And although the alcohol flowed from every conceivable direction throughout this period, in addition to the booze still being produced in the U.S.A., it was Canada that emerged as perhaps the most ridiculously prolific source of contraband hooch in Prohibition-era America. Led by the enterprising likes of Samuel Bronfman, who turned some solid business sense and a willingness to flout U.S. law into one of the continent’s biggest fortunes, Canadian distillers, blenders and bootlegging operators were able to ship night-inconceivable amounts of booze to thirsty U.S. cities by pretty much every vector imaginable. It was a process that made many people fabulously wealthy, building several companies that are still among the world’s biggest alcohol producers today as a result.

But why was Canada such a bastion of Prohibition-era alcohol production, and how did they get all that liquor to thirsty Americans? It’s a story still being mythologized today by the spirits industry itself.

The Many, Many Sources of Prohibition Booze

The popular conception of the Prohibition era, and even the pop-history side of how the era is presented, fail to get across just how many different ways alcohol could end up in a person’s mug from the years 1920-1933. It certainly didn’t all need to come from out of the country, from Canada or elsewhere, that’s for certain.

To begin with, there were a bevy of exceptions made in the U.S. when it came to alcohol production. Home winemaking and cider making from one’s own fruit was never outlawed during Prohibition, effectively having been used as an incentive to get rural citizens and farmers to back temperance efforts–they were promised a chance to keep their own alcohol, while stripping it away from the more “foreign” and minority representative populations of the densely populated cities. At the same time, however, city dwellers were able to take advantage of loopholes for things like “sacramental wine,” which encouraged the formation of thousands of fake “wine congregations” buying homemade wine from enterprising winemakers who doubled as phony ministers or pastors.

So too did legitimate alcohol sales continue in other forms such as the booming pharmacy industry dispensing “medicinal” whiskey from the handful of large American distilleries granted these permits, the likes of Brown-Forman and George T. Stagg Distillery (now Buffalo Trace) among them. This booze was joined by vast amounts of industrial alcohol produced in centers such as Philadelphia, ostensibly intended for commercial purposes but instead diverted toward more illicit uses. The denatured, undrinkable alcohol produced by large Philadelphia chemical corporations would be purchased and sent to other dummy chemical corps to have poisonous denaturants (hopefully) removed through redistillation, before the resulting unaged alcohol was flavored to vaguely resemble the likes of gin or whiskey. These spirits could be sold as-is, or cut with legitimate commercial liquor to stretch out stocks of bourbon or scotch and increase profit in the process. Anything was fair game, in an underground market with very little need for quality control.

For any shipment actually intercepted by Prohibition agents, 100 more got through just fine.

But despite all the homegrown sources of booze during Prohibition, it is true that much of the liquor consumed in the U.S. during this period also came from abroad, particularly if one lived within a reasonable distance of the coast or border. On the East Coast in particular, it was particularly easy to lay hands on commercial spirits produced in the U.K. or Caribbean, which would arrive via ships anchored outside the tree mile limit of international waters, easily accessed by small boats–even the rowboats of determined drinkers–who could use the moored ships as floating liquor stores. The idea of federal Prohibition agents somehow being able to enforce the law here, or catch those buying vast quantities of booze by night from floating ships and then distributing it inland, was nigh laughable–in his book Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition, author Daniel Okrent notes that when Prohibition began in 1920 there were less than 30 Coast Guard vessels available for “patrolling” the entire American coast. Even the government’s eventual move to increase the range of international waters out to 12 miles from shore did little to curtail the flow of booze from these floating dispensers, though it may have stopped those plucky rowboats.

To get a sense of the scale of this illicit liquor flow, you have to remember that producers in the U.K. or the Caribbean were effectively trying to replace the entire commercial beverage alcohol industry of the U.S.A., which meant that a gigantic new market of opportunity had opened up, regardless of the fact that their product was technically illegal. The ripple effects, meanwhile, led to the waystations of this trade becoming major shipping centers practically overnight. For example, the sleepy ports of The Bahamas turned into bustling hubs of activity in the early 1920s as Nassau became a huge center for the storage and shipping of alcohol from Europe and elsewhere in the Caribbean. Per Okrent, in 1918 scotch exporters sent a mere 914 gallons of their product to The Bahamas. In 1920? They sent 386,000 gallons there. And it wasn’t a mystery where the booze was going next.

Canada, meanwhile, ironically had its own versions of Prohibition on the books in its various providences in the 1910s and 1920s, but enforcement in many places was even more lax than it was in the United States. Nor did even the Canadian provinces prohibiting the sale of alcohol dare to prohibit the manufacture of alcohol for foreign markets–the country was not about to give up the lucrative export taxes of the liquor industry. And if that liquor should end up in the United States? Well, that was America’s problem, wasn’t it?

Sam Bronfman: Canada’s Liquor King

The dawn of the Prohibition era in the United States was a golden window of opportunity for a certain breed of cutthroat, ambitious businessman, and there was no one who fit this mold more perfectly than Samuel Bronfman. Born aboard a ship en route to Canada, his wealthy family hailed from present day Moldova and fled the Russian Empire as refugees from antisemitic pogroms of the day. Settling in Manitoba, the Bronfmans were effectively forced to start from scratch, gradually acclimating to the culture and extending their business interests far and wide–first into lumber, and then frozen fish, before entering more lucrative trades in horse supply and the bar and hotel industry. It was here that a teenaged Sam Bronfman noted the most lucrative aspect of the hotel business: The booze. That observation would be the first step in a bootlegging operation that would build his family into some of Canada’s most prominent billionaires. He would build his empire with the indispensable but not often publicly acknowledged help of his brothers Harry, Allan and Abe.

As Prohibition began in the U.S., the first order of business, believe it or not, was for Sam Bronfman and his brothers to lay hands on as much U.S.-made liquor as they possibly could. After all, they didn’t yet own means of alcohol manufacture, so the game was to buy and import as much booze as possible, which could then be discreetly shipped back down to the now dry United States. As Okrent notes in Last Call:

“In the very beginning of the Bronfmans’ cross-border business, the liquor flowed upstream, as American distillers disposed of much of their presumably valueless inventory by sending it to Canada. In the first year of U.S. Prohibition the Bronfmans imported some 300,000 gallons of whiskey from American distilleries, mixed it with raw alcohol and water, and began shipping a much larger quantity of seriously degraded product back across the border. When their supply of Old Crow and Sunny Brook and other American brands ran out, the Bronfmans began importing enormous quantities of pure neutral spirits from Scotland, diluting it, and adding appropriate coloring. Before the end of the year they were sending 26,600 cases–almost 64,000 gallons–of their goods back to the United States each month.”

But that was just the beginning. What Bronfman really needed to establish was a major source of his own liquor production, and again he turned his gaze toward the United States in acquiring it. In the course of his honeymoon after marrying Saidye Rosner in 1922, Bronfman toured the U.S.A. with his new wife, making special stops to visit now-shuttered distilleries. He ultimately found what he was looking for in Kentucky (surprise), where he purchased the entire Nelson’s Green Brier distillery (now reestablished) for pennies on the dollar and then had it disassembled and shipped to Canada, where it was reassembled and began producing liquor once again. Its new home was the Montreal suburb of Ville LaSalle, Quebec being chosen because it was the “wettest” of Canadian provinces thanks to its wine-loving French ancestry. Here, Bronfman could begin the mass scale production of inexpensive, unaged whiskey, which he would then blend with higher quality imported whisky from Scotland, selling the result as “Highland whiskey.”

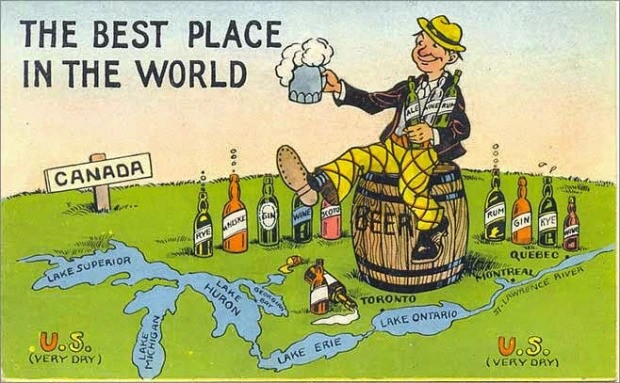

A Canadian postcard from the late 1920s, highlighting the Great White North as America’s wet neighbor.

From this point, the empire’s growth became a self-sustaining monolith. Bronfman’s Distillers Corporation Ltd. did massive business to the illicit American market, supplying the lion’s share of booze for big northern cities like New York, Chicago and Detroit. In 1928, the company absorbed the competing Joseph E. Seagram & Sons and unified under that name, in a move that would create one of the biggest and most prosperous Canadian companies of the 20th century. Before its late 1990s implosion, Seagram had become the world’s largest owner of alcoholic beverage brands, enriching the extended Bronfman family of shareholders with a fortune built on a legacy of bootlegging.

Of course, one might wonder: How were the likes of Sam Bronfman truly able to feign legality in sending all this liquor to the United States during Prohibition? Well, there were countless ways to get around the limitations of the law. Perhaps the most effective developed by Bronfman and co., though, was their use of the tiny island of St. Pierre off the coast of Newfoundland, which still maintains its status today as a territory of France. This was an opportunity for Bronfman: Liquor could officially be “exported” to St. Pierre, but once there it could simply be packed up and sent to the porous American coast. And as long as the proper export taxes were paid, the Canadian government had little incentive to care any more than that. Before long, this booming business brought the same kind of bustling activity to St. Pierre as it had brought to the likes of Nassau. Per Okrent, in Last Call:

“In any given week, Bronfman had a million dollars’ worth of inventory stashed on the North Atlantic island of St. Pierre. Virtually every man, woman and horse on the island was engaged in unloading, storying, and reloading liquor destined for the United States; many houses were shingled with used packing crates.”

Of course, it really wasn’t much more difficult to bring booze in straight over the border between the U.S. and Canada, thanks to the ability of bootlegging dollars to grease all the right palms along the way. On the East Coast, fishermen gave up their nets and reels to become much more profitable alcohol smugglers, picking up at distribution centers north of the border and dropping off at clandestine points south of it. Land entry across the border in small towns of states such as North Dakota (especially by rail) was as simple as legally going through Canadian customs, paying the appropriate export duty, and then bribing the American border agents or Prohibition agents on the other side. Other Canadian distillers simply claimed they were internationally exporting their wares to Mexico or the Caribbean, and that those cases of liquor were simply “passing through” the U.S. rather than coming to rest there. To support this scam, they would submit falsified landing certificates from ports such as Havana in order to claim that the product had been shipped and received there.

Various Canadian jurisdictions, meanwhile, effectively washed their hands of widespread bootlegging operations by simply ruling that U.S. law was a moot point in Canada. In Windsor, Ontario, just across the titular river from Detroit, local officials declared that U.S. law couldn’t compel Canadian citizens to follow it. Soon, a vast array of private boats dubbed the “mosquito fleet” were swarming back and forth across the river at all times of day, loaded down with beer and whiskey. Meanwhile, federal Prohibition agents in the area didn’t possess a single boat of their own. There was no hope of stemming the flow of illicit alcohol; any earnest attempt at enforcement was always destined to be hopelessly outmatched by the collective efforts of entrepreneurs who knew there was profit to be made.

This was the setting that allowed the likes of Sam Bronfman to flourish, ultimately changing the course of the North American spirits industry forever. Even now, one of the most hyped releases from Sazerac Co.–which is saying a lot, given that this includes all Buffalo Trace products, etc.–is the ultra-limited Mister Sam Tribute Whiskey, a mysterious blend of American and Canadian distillate that is dedicated to Bronfman. As Sazerac Co. describes it:

The mighty Sam Bronfman, Seagram’s first master blender, revolutionized the art of blending as he built his Seagram Company into a massive spirits empire. Our Master Blender, Drew Mayville, comes from this Seagram master blender lineage. Before he came to Sazerac, Mayville was the last master blender at Seagram’s and his mentor was Seagram Master Blender Art Dawe, who worked directly with Sam Bronfman. Mayville created this perfect blend through experimentation and precision and it is fittingly bottled at our Old Montreal Distillery in Montreal, Quebec.

The legacy of “Mister Sam” lives on.

Of course, in reading about this $300 MSRP bottle–which you’ll find on the secondary market closer to $3,000–one will note that there are no references to be seen to the illicit industry that first built Bronfman’s Seagrams into such a global powerhouse. That side of the company’s history has been washed and scrubbed away as much as possible in the intervening decades, as Bronfman and his biographers did what they could to put a respectable face on his “rags to riches” story. Today, the Bronfman name is known more for tabloid appearances and philanthropic pursuits than its intricate bootlegging operation during Prohibition, the seedy origins of the fortune having gradually sunk into the mists of history.

For American drinkers during those 13 “dry” years of federal Prohibition, however, Bronfman’s enterprises were more than welcome. Together, he and other Canadian distillers kept the party going until our own commercial alcohol industry could finally return for its second act.

Jim Vorel is a Paste staff writer and resident beer and liquor geek. You can follow him on Twitter for more drink writing.