Cocktail Queries: 5 Questions about Rum

Photos via Unsplash, Malte Wingen, Gianluca Riccio, Artem Beliaikin

Cocktail Queries is a Paste series that examines and answers basic, common questions that drinkers may have about mixed drinks, cocktails and spirits. Check out every entry in the series to date.

As we’ve already opined from time to time in the past when writing about spirits, there’s perhaps no other style of liquor that breeds so many misunderstandings and misconceptions as rum. As I myself wrote last year when dismantling the idea of “dark rum” as a style:

Of all the major liquor families to populate the well of your average bar, none is so fundamentally misunderstood on almost every level by the American consumer as rum. And really, it’s not their fault—rum, as a topic, seems to possess an almost mystical power to compel mythology and misinformation. Its histories are murky and rife with inaccuracy. Many national rum industries get away with inconsistent or downright misleading labeling practices. Unlike homegrown American liquor terms such as “bourbon,” merely seeing the word “rum” barely gives you any information at all as to what is inside a bottle. It’s the most confounding of the major spirit categories … and one of the most delicious as well.

And that confusion no doubt means there are rum questions out there waiting to be answered. So here are our answers to five of the most common questions you may have about rum. Also: Check out our blind tasting of 10 bottom-shelf white rums for less than $15.

1. What is the definition of rum?

In a single sentence: Rum is an alcoholic liquor made via the fermentation and then distillation of molasses or sugar cane juice. It is defined, then, by the source of its fermentables—whereas something like the vague concept of “vodka” can be produced from fermentables that range from potatoes and corn to wheat or rye, the starting point of rum always comes back to sugar cane.

Notably, rum can be produced from either the pure juice of crushed sugar cane, or the byproduct we know as molasses. We call molasses a byproduct because that’s what it is—it’s created via the process of refining sugar cane juice into crystalized sugar. Each time that the sugar cane juice is boiled, sugar crystals form and the remaining liquid further concentrates and caramelizes, becoming darker and darker styles of molasses. Industries thus sprung up around how to use this byproduct, incorporating it into cooking and various styles of baking. But one of the biggest uses of molasses has always been rum production, and rum made from molasses has always accounted for the vast majority of all rum that is produced. Rum produced directly from sugar cane juice has a very different flavor profile and identity, which we will discuss in more detail below.

You can’t have rum without sugar cane.

You can’t have rum without sugar cane.

Beyond that basic definition, however, the idea of “rum” is quite nebulous, and each sovereign nation may have very different requirements for its production and maturation. Some locales require a year of aging for all rum products, while others do not. Some distilleries focus more on expressive pot still distillation, while others stick to cleaner and lighter column stills. Many rums that are aged see time in used American whiskey barrels, but others are aged in wooden barrels of every possible description—wine, sherry, port and beyond. Some rums are even aged in stainless steel rather than in wood at all, or are filtered after being aged in wood in order to remove their coloration.

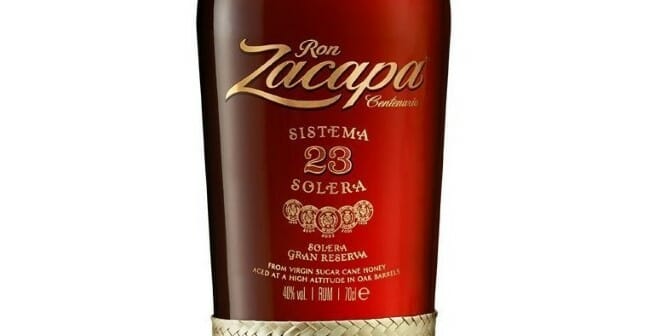

A good rule of thumb: If you want legitimately aged rum, look for an actual age statement. Not just a number on the label, mind you—an actual age statement that has the word “years” after it.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Many classic cocktail rums are in the English style.

Many classic cocktail rums are in the English style. Tiki drinks would be a lot less interesting without rhum agricole.

Tiki drinks would be a lot less interesting without rhum agricole. A particularly misleading “23.”

A particularly misleading “23.”