Cocktail Queries: 5 Questions about Scotch Whisky

Photos via Unsplash, Adam Wilson, B K, Anders Nord, Marvin L

Cocktail Queries is a Paste series that examines and answers basic, common questions that drinkers may have about mixed drinks, cocktails and spirits. Check out every entry in the series to date.

Scotch sort of occupies an unusual position in the modern alcohol hierarchy, doesn’t it? For decades, high-end scotch was the most sure sign of “cool” available to screenwriters and set decorators. Need to communicate to the audience that this character is a suave, sophisticated gentleman? Show him drinking some neat scotch, or scotch on the rocks. Where would the likes of Mad Men have been without it?

But in the modern mixology and cocktail culture boom, it sometimes feels like scotch has been left behind a bit. Whereas American bourbon (and especially rye) whiskey, rum, tequila, mezcal and gin have all seen surges, scotch hasn’t quite had the same attention, nor has it been reclaimed as a cool hipster drink in your average dive. Perhaps it’s only a matter of time, though, until scotch sees its moment in the sun?

There are, after all, no shortage of classic scotch cocktails such as the Rusty Nail, Rob Roy, Presbyterian or Penicillin. And with all of the new drinks that have been developed with the likes of mezcal in mind, perhaps some could be ported over to the original smoky European liquor: Scotch!

But beyond the cocktails, let’s answer the more basic questions: What is scotch? What’s that whole “single malt” designation all about? What are the scotch whisky regions? How does its flavor differ from American whiskeys, such as bourbon and rye? What should “good” scotch cost you at the package store these days?

Here then, are five questions about scotch you’ll probably want answered. Also: Check out our blind tasting of 10 bottom shelf scotches for less than $25.

1. What is the definition of scotch whisky?

First of all: It is indeed “whisky,” when you’re talking about scotch. The Scottish have never used the “e” in their spelling of whisky, whereas American, Canadian and even Irish whiskeys often do. There are of course a few exceptions, but when you’re talking about scotch, just spell it “whisky.”

Here are the basic outlines of what defines both scotch whisky, and “single malt” scotch whisky.

— Scotch must be produced in Scotland—fermented, distilled, aged and bottled in its country of origin. You may see bottles on the shelf labeled as “scotch-style” whisky that are from the U.S. or Canada, but if it actually says “scotch,” then it hails from Scotland.

— Historically, scotch whisky was first distilled from a fermented mash of malted barley, but modern scotch can also include other cereal grains such as wheat, corn, rye and others. As in any liquor, the sugars derived from mashing these grains are first fermented, and then distilled to a proof of less than 190, before being cut with water. All scotch whisky is then legally required to spend at least three years aging in oak, with a maximum size on casks—this is the same rule also required of Canadian whiskey. It is then bottled at a minimum strength of 40% ABV (80 proof), the same as in U.S. whiskey.

— The oak casks used for scotch whisky, however, are traditionally of a very different nature than what is being used for American bourbon and rye, although they are in fact the exact same casks. The difference is that American bourbon is required to age in newly charred casks, which impart much more intense and wood-forward flavors, in a shorter period of time. Scotch whisky, on the other hand, is traditionally aged in used casks of many different varieties. Used American bourbon casks make up a large percentage of the oak barrels used by the scotch industry, and can be re-used multiple times, but they contribute less intense flavors because the first round of American whiskey aging sucked many of those flavors out of the wood. However, this is really just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to scotch barrels: The industry also makes use of rum barrels and casks used to age sherry, port, wine and many other spirits. Even “virgin” oak, which is newly charred as in American whiskey, is starting to be used more frequently as the industry has increasingly become less reliant upon tradition.

Used barrels are essential to the scotch industry.

Used barrels are essential to the scotch industry.

— Scotch whisky is not allowed to contain any “added substances,” with the exception of plain (E150A) caramel coloring, which is standard in the industry for altering the color of scotch to levels desired by the consumer. This practice is still somewhat contentious, and distilleries may label their product as “bottled at natural color” to inform consumers that they didn’t use caramel coloring.

— Any age statement on a bottle of scotch “must reflect the age of the youngest whisky used to produce that product.” If a whisky age statement reads 12 years old, therefore, it may actually contain older whiskies in it, but the youngest whisky in the blend is 12 years old. Conversely, a whisky without a numbered age statement is simply referred to as “NAS,” non-age-stated, although you know it’s legally required to be at least three years old.

— The most popular scotch whisky brands in the world are all “blended scotch whisky,” which is a legal term meaning that the product is a blend of both malt whiskies and grain whiskies. Malt whiskies, as the name would imply, are fermented and distilled exclusively from malted barley. Grain whiskies, on the other hand, are distilled from any other mash of grains. These include flagship brands such as Johnnie Walker, Dewar’s, Famous Grouse and many others, and are often characterized as more affordable and common for blending and mixed drinks, although ultra-premium blended scotch whisky also exists.

The most common and widely consumed scotch whiskies are blends of malt whisky and grain whisky, and are less expensive as a result.

The most common and widely consumed scotch whiskies are blends of malt whisky and grain whisky, and are less expensive as a result.

— “Single malt” scotch whisky, on the other hand, is typically characterized as a distillery’s most prized product, and single malt brands tend to carry higher price tags as a result. The word “single” specifically means that this is a whisky that was distilled by a single distillery, and “malt” means that the whisky contains no grain whiskies—it is exclusively malted barley. Taken together, it means that single malt whiskies are viewed as the purest expression of one distillery’s craft.

-

-

-

-

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 3:10pm

-

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:57pm

- Urls By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:57pm

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:55pm

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

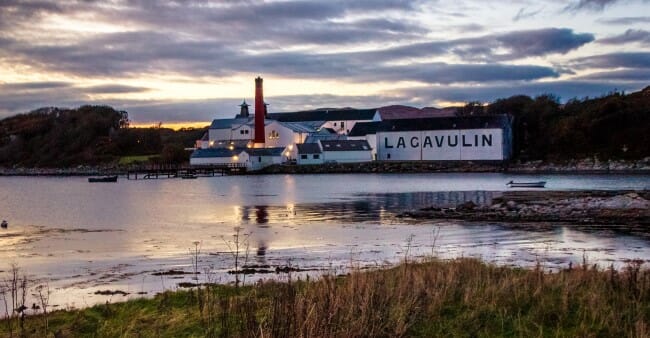

The seaside distilleries of Islay do not play around when it comes to bold flavors of peat and smoke.

The seaside distilleries of Islay do not play around when it comes to bold flavors of peat and smoke. You’re not going to find an American bourbon that tastes like this.

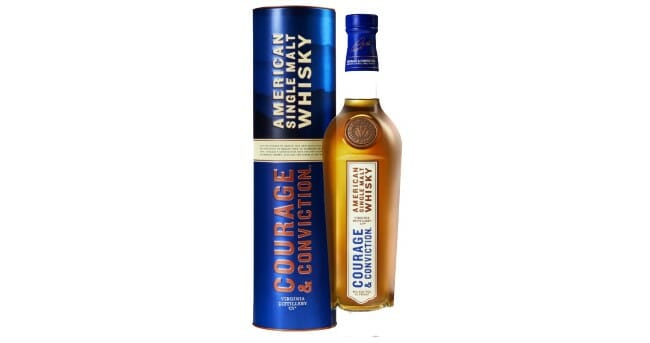

You’re not going to find an American bourbon that tastes like this. Places like Virginia Distillery Co. are focusing entirely on American single malts.

Places like Virginia Distillery Co. are focusing entirely on American single malts. Our blind tasting of bottom-shelf scotches was … illuminating, to say the least.

Our blind tasting of bottom-shelf scotches was … illuminating, to say the least.