Cocktail Queries: What Exactly Is “Whiskey Fungus,” and Is It Dangerous?

Photos via Creative Commons, By Shadle, Roger Griffith - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0

Cocktail Queries is a Paste series that examines and answers basic, common questions that drinkers may have about mixed drinks, cocktails and spirits. Check out every entry in the series to date.

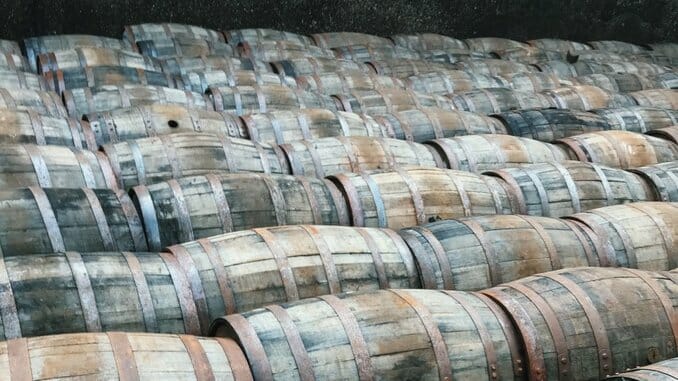

If you’ve ever gone on a tour of one of the major Kentucky bourbon distilleries, it’s a sight you’ve almost certainly witnessed–row after row of sky-high, wooden or tin warehouses (they’re called rickhouses in the industry), inside which one will find millions of barrels of whiskey statewide patiently aging. The numbers of barrels aging in these structures has skyrocketed in the last decade, as the whiskey industry has played catch-up to accelerate its production, years behind the curve of matching demand for many sought-after brands. This has meant the construction of many new rickhouses, an ongoing project that has in turn drawn attention to one of the industry’s less aesthetically pleasing sights: Whiskey fungus.

It’s another visual that you may very well have noticed while touring that big Kentucky bourbon producer: Rickhouses that are stained halfway up their sides (or entirely, in some cases) with a peculiar, black, grimy substance. Tour guides may have even pointed out why the rickhouses looked so strange or dirty, and the answer is all because of fungi. Specifically, the species that is generally referred to as simply “whiskey fungus,” which voraciously feeds and multiplies on a diet of alcohol fumes, which can obviously be found in abundance in the proximity of so many whiskey barrels. Rickhouses are the natural biome of whiskey fungus, and have been since at least the 1800s, when the species was first described. With the scientific name of B. compniacensis, the fungus was observed in France as early as 1872, blackening the walls of buildings near brandy distilleries. It has since been observed around the world, in Asia, Europe and the Americas–anywhere that barrels are left to age, leaking ethanol fumes into the air in the percentage of lost spirit over time that has classically been referred to as “the angel’s share.”

Historically, whiskey fungus has mostly been thought of as a rather innocuous eyesore. Most researchers say it’s not particularly destructive to structures or plant life, though it is extremely hardy, being able to grow in conditions of rapid temperature shifts that would kill most fungal species. It’s never been demonstrated to have any specific, adverse effect on human or animal life. Most people have never even seen whiskey fungus, except in the immediate vicinities of the rickhouses. But as the number of barrels aging in states such as Kentucky and Tennessee has continued to creep up, more small communities now find themselves being embroiled in bitter feuds over whiskey fungus, which has increasingly been characterized as an invading menace wreaking havoc on communities located near distillery property or warehouses.

A tree branch, coated in black whiskey fungus.

The most high profile of these fights has been ongoing for some time in Lincoln County, Tennessee, where the country’s largest producer of American whiskey, Brown-Forman’s Jack Daniel’s, has six barrel warehouses, with intent to build twice as many on another property. There, various residents have complained that the whiskey fungus has become a genuine problem, encrusting plants, trees, homes, cars and patios with sooty black particulate, allegedly fed by the alcohol fumes wafting from rickhouse sites. One resident took her complaints to the next level, suing the county in January, and claiming that the rickhouses near her wedding venue property lacked the necessary permits. In response, a judge recently halted construction on a new rickhouse, according to the New York Times. The resident, Christi Long, claimed her and her husband’s business had been damaged by the invasive fungus, which they attempted to remove every three months via pressure washing and bleach treatments. The fungus, she said, always returned.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-