Rise of the Machines: Can Artificial Intelligence Replace Your Therapist?

Photos courtesy of Lexi MorelandDystopian science fiction movies are always fun, in part because they exist just on the edge of what is possible. Movies like Blade Runner, Ex Machina, and Her portray a future that seems not so far from our own, a future where people are bossing realistic AI robots around and falling in love with them. They make AI look dangerous but enticing—as though if society could only thread the needle and avoid total annihilation, then the earth’s population’s true potential as a species would be unlocked.

This was the kind of thing we could daydream about until November 2022, when OpenAI launched ChatGPT4, and it started to become true. But AI didn’t just take over our dirty jobs like Rick Deckard in Blade Runner or Samantha in Her; it took over the arts. The Writers Guild of America and SAG-AFTRA both went on strike in 2023 to combat AI taking over their jobs. And now, in another twist of fate that no one saw coming (or ever really wanted), developers are creating AI psychotherapists.

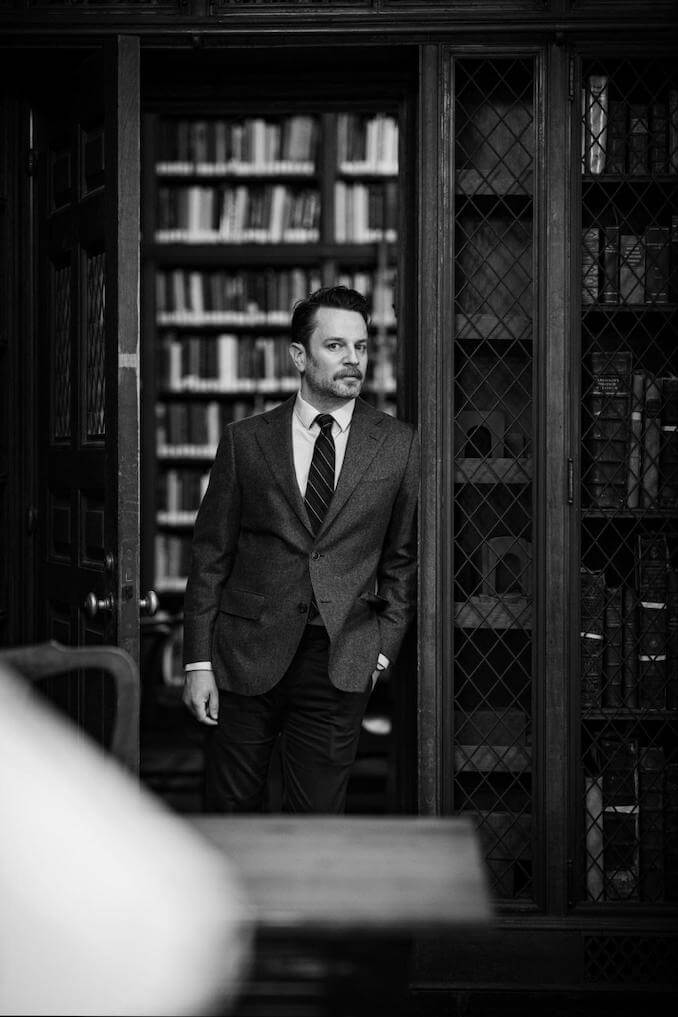

I sat down with Jordan Conrad, a psychotherapist and the founder and clinical director of Madison Park Psychotherapy in New York City, to discuss whether this is just hype or if we can look forward to AI therapists.

Dr. Conrad is just the right person to talk to. “My PhD is actually in philosophy,” he tells me as we sit down. He has those friendly-but-serious eyes that therapists sometimes have and talks in a calming tone that makes it easy to listen to him, even as our conversation moves to harder topics. “The word ‘crisis’ gets thrown around a lot these days, but there is a real problem in mental health worldwide,” he says. “AI has a lot of promise: to reach people in geographically isolated places or those where there just aren’t many therapists.”

The problem is whether AI provides a therapy worth wanting. Many AI psychotherapy developers claim to have high-tech features like mood trackers that can predict psychotic episodes before they even happen, but none of these are currently on the market. “Worse yet,” he explains, “most mental health apps have shoddy safety information or, in some cases, none at all.” It is almost hard to believe, after decades of science fiction, that safety wasn’t a top priority, but then I remember: greed. Ah, right…

I ask whether the safety problems can be managed by using one of these apps alongside a normal human therapist. “That might help reduce some of the problems, but professional organizations haven’t provided much guidance on how to incorporate these into our normal practice.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-