The Hard Part’s Getting Away: The Versatility of Gene Hackman, as Seen through His Five 2001 Films

Earlier this year, a picture of Gene Hackman taken in May 2019 went viral on Twitter, with folks around the internet gathering to share their appreciation for the 91-year-old actor. Particularly for a place as ridden with heated daily debates about Eternals Rotten Tomatoes scores and whether or not it’s okay to watch Dune on HBO Max, seeing the Twitterati collectively unite to pour love on the two-time Oscar winner is representative of how Hackman’s gifts transcend any possible divide. He’s an actor you always recognize, yet he plumbs new depths and dimensions with each role he takes on, never failing to find the rhythms of the world around him. Whether you’re into disaster blockbusters, revisionist Westerns, paranoia thrillers or slapstick comedies, there is a Gene Hackman performance out there for you.

With the actor back in the discourse sphere, discussion inevitably led to a topic oft-mentioned: That of the disappointment that Hackman’s illustrious career ended with 2004’s critically reviled Welcome to Mooseport, a political comedy that sees Hackman’s retired U.S. President run a mayoral race against Ray Romano’s everyman. While it’s understandable for cinephiles to wish that their favorite artists end their careers on a high note, bemoaning this film as a nadir in a 40-year career does a disservice to the fact that Hackman was playing at the peak of his abilities right until the very end. While some of his contemporaries who dominated 1970s Hollywood could rightly be considered to have fallen into taking low-effort paycheck gigs in their later years, Hackman didn’t slow down for a moment until he unofficially retired post-Mooseport.

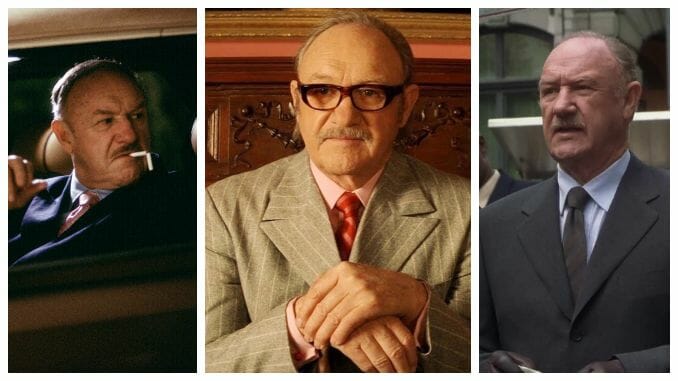

One only needs to look three years earlier than his final film to see the level of versatility he demonstrated, a recurring theme throughout his lengthy career. 2001 didn’t just bear witness to a single great Hackman performance; it saw him run a streak across five entirely distinct films, delivering in each a performance totally unique from the rest. It’s a body of work across one year that proves the elasticity of an actor who could always be counted on to deliver. The rarity of an actor taking big swings the way that Hackman did and still not missing is something that is unfortunately not appreciated enough when it comes to appraisals of his work, despite the laudits given to him since his early years.

2001 began in an unexpected place for the actor, with a sneaky eleventh hour role in Gore Verbinski’s romantic action comedy, The Mexican. Starring Brad Pitt and Julia Roberts as a chaotic couple on the outs, the narrative crux of the film finds Pitt traveling south of the border to pick up an allegedly cursed firearm for a man named Arnold Margolese, an incarcerated mob boss Pitt is indebted to. Throughout the film, we hear bits and pieces about Margolese, giving us the impression of him as a larger-than-life figure, a mysterious man you wouldn’t want to cross. It’s not until the very end that we actually meet him, played in a one-scene performance by Hackman.

Regaling Pitt with a tale of how several years in the slammer have transformed him, Hackman holds the responsibility of conveying the entire history of a character, the entire core of who this man is, in a single scene. He manages it without breaking a sweat. To put the pressure of capturing this man who has been discussed the entire film onto an actor for one scene, and one scene only, is a great deal for anyone to take on. Hackman not only has to be believable as the unnerving criminal kingpin Margolese once was, but also the changed man he has become. It’s almost an impossible task, as you enter a Catch-22 situation where the actor needs to be someone recognizable enough to the audience to immediately make an impression, yet we also have to be able to see this character for who he is—as opposed to it being Tom Cruise in Tropic Thunder, where part of the fun is the fact that we all know that’s Tom Cruise being ridiculous in a minor role. Hackman toes the miniscule line necessary to find success, ably underplaying the gravity of the role in a way that allows us to see him as a human being underneath the ominous shadow that has been cast over this man’s name for the entirety of the movie.

It’s rare for a star as big as Hackman to show no hesitation in taking on supporting roles, yet it was something he did with regularity. While he had showy leading parts in 2001, he also took a step back from the dynamic duo of Sigourney Weaver and Jennifer Love Hewitt in David Mirkin’s con artist comedy Heartbreakers, an underrated gem that perfects the “Dirty Rotten Scoundrels but they’re women” formula that The Hustle botched twenty years later. Weaver and Hewitt play a mother/daughter pair who use their sexuality to fool men into giving up half of their fortunes, with Hackman coming into the picture as their biggest target yet. The film is a broad farce, and Hackman leans into this with aplomb, taking on the role of a tobacco baron with a cigarette in his mouth every second he’s on screen. An absolutely deplorable wretch, this is Hackman at his most wildly unhinged, a scene-stealing turn that chews just enough scenery to ignite laughing fits whenever he’s around while never attempting to upstage the film’s stars.

-

-

-

-

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 3:10pm

-

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:57pm

- Urls By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:57pm

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:55pm

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-