Knock at the Cabin Is a Great Thriller and an Insulting Adaptation

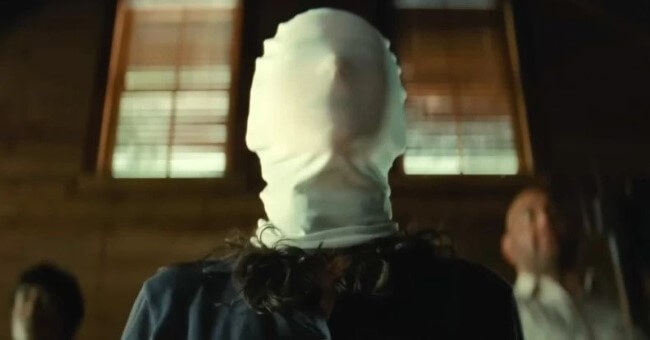

M. Night Shyamalan’s Knock at the Cabin is one of the man’s most confident, assured directorial efforts since the likes of Signs and The Village. It’s a handsome film, though shot a little idiosyncratically at times—it often lives inches from characters’ faces, like a canted take on the uncomfortably close conversations of Jonathan Demme’s The Silence of the Lambs. As an old-school thriller, though, Knock at the Cabin checks all the boxes: It’s a pulse-raising, suspenseful good time, featuring both the director’s own signature fusion of emotion and mysticism, and another wonderfully nuanced performance by hulking thespian Dave Bautista. As is so often the case in his career, a focused setting and story produces more satisfying results for Shyamalan than when he’s allowed to run wild with his own overindulgent concepts.

This is likely to be the perspective of someone seeing Knock at the Cabin, if they’re not familiar with the film’s source material, 2018 novel The Cabin at the End of the World by decorated horror author Paul G. Tremblay. If a viewer is familiar with Tremblay’s novel, however, the assessment of Knock at the Cabin almost can’t help but change radically. Because although Shyamalan has crafted an effective thriller on its own merits, the reality is that Knock at the Cabin is a painfully dismissive adaptation of its own source material. Seemingly faithful for the vast majority of its runtime, Shyamalan veers off in the final 20 minutes, irretrievably altering the outcome, themes and indeed the entire point of Tremblay’s book. Really, “altering” isn’t even a strong enough description—Shyamalan effectively reverses almost every bit of Tremblay’s intention into the exact opposite. It’s one of the more insulting adaptations of an author’s work you’re likely to see, and although Tremblay has been polite in discussing his opinion of the movie—as you’d expect from an author who has been cut their first ever big Hollywood check for a film adaptation—he does indeed admit that he prefers his own ending. I can only imagine how he must genuinely feel.

“There were times where I was tearing up at random things just because, wow, it was right out of the book,” said Tremblay in a just-published interview with the L.A. Times. “And other times I felt like I wanted to run out of the theater.”

I wouldn’t blame Tremblay for doing exactly that. From the moment I read The Cabin at the End of the World last fall and found out that Shyamalan was adapting it, this is pretty much exactly what I was afraid might happen.

In fact, I wrote as much in November, in a piece entitled “Can M. Night Shyamalan Really Deliver a Faithful Adaptation in Knock at the Cabin?” Diving into the the themes of the book, I questioned whether Shyamalan and Universal Pictures would have the guts to depict certain key moments from the novel, and whether Shyamalan would be able to resist his own compulsion for revelatory twists in order to preserve the novel’s single most consistent theme, which is that of uncertainty and a lack of easy, satisfying answers. As I wrote at the time:

Perhaps more important, though, to the spirit of Tremblay’s book, is the following question: Does M. Night Shyamalan have it in him to adapt and depict the uncertainty and doubt in Tremblay’s story? Will producers be okay with a story that never truly picks a side, or reveals if the protagonists or antagonists were “right”? And as a writer, will Shyamalan be able to bring himself to depict an ending that is adamantly free from a big reveal or dramatic twist? The twist ending, after all, is associated so strongly with Shyamalan’s career that the director’s very name is used to imply a zany twist. And to be honest, I’m not sure that Shyamalan can stop himself from trying to “spice up” Tremblay’s work with an ending that the audience can view as more definitive and revelatory.

So at the end of the day, it comes down to this: Which seems more likely? That M. Night Shyamalan would present a faithful, grounded version of The Cabin at the End of the World, capturing its unique tone of uncertainty and gray moralism? Or that he’ll deliver the type of film he’s been known for throughout his whole career, a Knock at the Cabin that eliminates the subtlety of Tremblay’s story in order to please the multiplex masses with a big, dramatic, emotional twist?

As predicted, Shyamalan goes with the latter, which really should be no surprise to any of us. But it’s still upsetting to watch the point of Tremblay’s story be trampled with such a cowardly, insulting adaptation, smashed by the director’s scriptural contributions with sledgehammer blows, exactly like one of its characters committing a messy ritual suicide.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-