Difficult Women: The Feminine Anti-Biopics of Mary Harron

This month sees the 70th birthday of Mary Harron, the Canadian filmmaker perhaps best known to the world for her work on American Psycho. The impeccable adaptation of Bret Easton Ellis’ controversial novel was seen as an impossible endeavor for any director, much less one with a single credit to their name. Yet Harron and her regular screenwriter Guinevere Turner turned the ultraviolent tale into a razor-sharp satire of male entitlement and the yuppie era. There’s a reason it’s widely considered her best work in a dishearteningly small filmography, but outside of Patrick Bateman’s blood-fest, Harron helped redefine one of the most maligned genres in mainstream filmmaking—and do so with an unapologetically feminist lens.

Dennis Bingham, perhaps the most celebrated scholar of biopic studies, described them as “a respectable genre of very low repute.” The biopic, in its purest form, is the most middle of the middlebrow, one that aims for prestige yet is limited in its creative ambitions. This is a genre defined by the most obvious of tropes, to the point of being the stuff of easy parody. The biopic is also typically focused on men, particularly those considered “geniuses.”

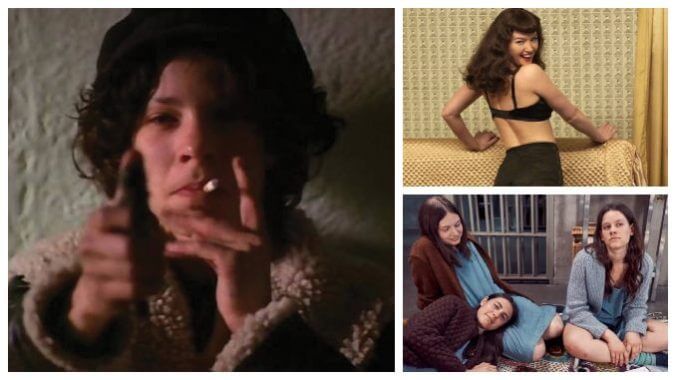

We’ve all seen countless films about the troubled yet inspiring lives of brilliant white men who overcame adversity, drugs and tragic childhoods. The role of women in these stories is usually limited to that of mothers and spouses. As Bingham noted in his book Whose Lives Are They Anyway, when the biopic turns its gaze towards the feminine, they are often stories of tragedy over accomplishment. History is a fickle beast, of course. Yet for Harron, these stories are ideal opportunities to examine the kind of women the biopic genre would usually avoid like the plague. Her trilogy of female-centered biopics (her most recent film, Dalíland, focuses on the artist Salvador Dalí) take women who never would have been expected to receive the lavish Hollywood treatment—Valerie Solanas, Bettie Page, and the Manson girls—and gives them the stories they deserve.

Harron’s debut, I Shot Andy Warhol, has little interest in the iconic figure of its title. If biopics are intended to demystify or deify genius, then Harron’s response is to show the artist as little more than a jerk, a guy who floats through his own life while others around him do the heavy lifting. For Harron, the figure of true fascination is Valerie Solanas, the troubled feminist writer of the SCUM Manifesto who would eventually try to assassinate Warhol.

As played by the always-underrated Lili Taylor, Harron’s Solanas is flinty, burdened by a tough life and ill-prepared for the new era that Warhol came to define. She is mentally ill, but Harron does not lay the blame for the shooting at any one easily categorizable quality. There’s no attempt to justify what she did, merely a hunger to remind everyone that she was as much a human as anyone else in Team Warhol (this also, mercifully, means that Solanas’ transphobia is not downplayed.)

Hugely militant at the time, the SCUM Manifesto now seems kind of obvious, and also incredibly self-aware in its humor. When Taylor reads from the book, shown intermittently through the film as minor sermons to the audience, she seems harsh but not lacking in sense. Like all women past, present and future, she is terrified of being reduced to a mere thing, something that Warhol’s Factory does to everyone that enters its orbit. Warhol, played with detached curiosity by Jared Harris, doesn’t seek to actively manipulate her but his default mode of dealing with people fulfills that fear for Solanas and others like Candy Darling.

Through Solanas, Harron reveals a very different death of the 1960s than she would in Charlie Says: The exposure of the true rot at the heart of the supposed radical change promised through Warhol’s world and its capitalist fetishism. Joan Didion once said of the Manson murders that she remembers how nobody was surprised by the news. The attempted murder of Warhol and the Factory dream feels similarly unsurprising, with Solanas’ ideals too much for a time that thrived on the status quo with a slightly shinier paint job.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-