20 Years Ago, The Passion of the Christ Scared a Generation of Christian Kids

When I was young, teetering on the edge of sleep each night, I would test my love for God. My fists would clench beneath the thin sheet, my eyes would scrunch closed, my muscles went rigid, shaking with the effort of my focus. I would think about all the good things in my life and tell God I loved him, counting each declaration as it ticked past; 10 times, then 20, then 50. No one had asked me to do it, not precisely, but the need for all-encompassing contrition was as ingrained in the fabric of Christianity as the forgiveness promised in exchange. If “the wages of sin is death,” this was my own act of repentance; childlike, yet costly.

According to Mel Gibson, the severity of the human condition, as defined by Christian doctrine, was never adequately expressed from the pulpit. He felt that as a filmmaker it was his job to convey the totality of Christ’s suffering, accurately capturing his gory final moments. It was a decision born of his own suffering, his idea of God settling into clarity after he prayed.

“Because of my experience I started to focus on the Passion of Jesus, which for me, growing up as a kid, had always been sanitized and not real, like a fairytale,” he explained.

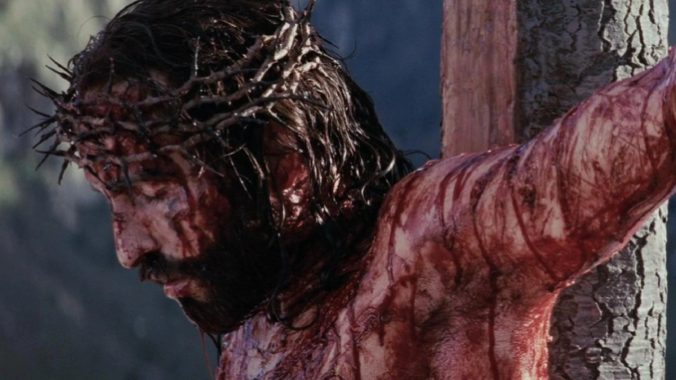

From this place of desperation, The Passion of the Christ came together. The first scene opens with Jesus (as portrayed by a committed Jim Caviezel, attempting a performance beneath gallons of fake blood) praying in the garden of Gethsemane while being visited by Satan (Rosalinda Celentano), who skulks around our sweaty protagonist, peering out beneath a dark cape. This is how the relatively simple retelling begins, with broad beats over-emphasized with slow-motion; a warning of the gruesome endurance test which unfolds over the next few hours.

The real legacy of Gibson’s passion project is how it was readily embraced by the Christian right, weaponized as a sharp, strange evangelistic tool. My own experience with The Passion of the Christ stretches back to the early 2010s, late into the age-old youth group tradition of the “lock in.”

Lock ins are somewhat self-explanatory: A group of teenagers are locked into a church hall for a co-ed sleepover. Every so often the merriment would be interrupted by a mini-sermon and an altar call (a chance for attendants to publicly announce their faith).

One year, at around 2 AM and in lieu of a sermon, they played the final half hour of The Passion of the Christ for a room of sleep-deprived tweens. My youth pastor stood at the front, providing a tearful commentary on Christ’s crucifixion, imploring us to commit our lives to God. Most of us sat dazed, the after-effects of our sugar highs wearing into dull headaches as we absorbed the blood and gore. A few people trudged up to the stage where they would at least have their backs to the images projected overhead.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-