This Is Unnecessary: Bad Boys II at 20

“Taking a close look at what’s around us, there…there is some sort of a harmony—it is the harmony of… overwhelming and collective murder.” – Werner Herzog in Les Blank’s Burden of Dreams

“WOOOOO!!!” – Mike Lowrey (Will Smith) upon witnessing considerable loss of life in Bad Boys II

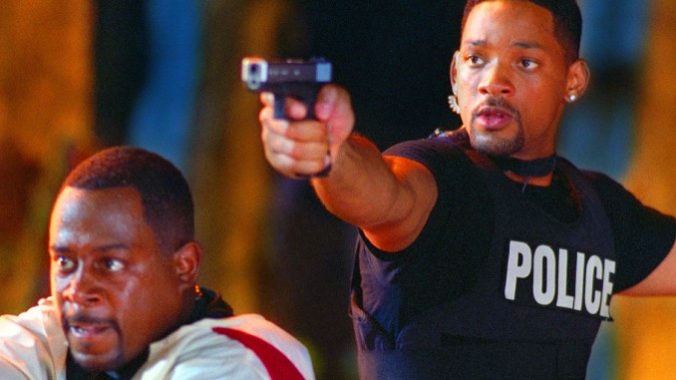

In Michael Bay’s sequel to 2007’s Transformers, Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen, Sam Witwicky (Shia LaBeouf)—an insufferable Bay protagonist in a legacy of them—scrawls ancient Cybertronian text on a dorm room poster of another Michael Bay movie, Bad Boys II. This self-reference bordering on self-reverence isn’t new. Last year’s AmbuLAnce mentions Bad Boys both explicitly (bystanders compare a moment to Bad Boys) and in imagistic shorthand, Bay mimicking his own regularly mimicked shot of Miami PD detectives Mike Lowrey and Marcus Burnett (Martin Lawrence) rising into frame as the simmering southern Florida skyline spins behind them. Capitalism ferments in the sun at the end of the world. Safe to say you probably know the shot: In Bad Boys II, Bay whips out the exact same shot again, only this time, Marcus slowly hangs up a mobile phone and adds, “Shit just got real.”

The older he gets, the less Bay resists the opportunity to allude, overtly and often, to the iconism of his previous films. But in 2009, with the Transformers sequel seemingly rushed into theaters just two years following the original, for Bay to point to Bad Boys II, the only other sequel he had (and has) ever made, feels like a deeper, more deliberate gesture towards his own work. Though Bay would continue to reimagine the Transformers movies as increasingly retconned dystopian odysseys, Revenge of the Fallen is the true follow-up to Transformers: Doubling down, without hesitation, on absolutely every impulse entertained in the first movie. Property destruction, death count, leering shots of Megan Fox’s body, an ever-complicating mythos, the irrepressibly psychotic might of the American military industrial complex, racist robots, incomprehensible CGI, the incessant whine of Sam Witwicky’s voice—all is amplified exponentially. And in the middle of it, Bay alludes to his archetypal sequel, released less than a decade before, on July 18, 2003. See Bad Boys II, Bay seems to say. That is what a sequel is supposed to be: Indulgent, reactive, loud and completely unnecessary.

A making-of documentary, included as a supplemental feature on the Bad Boys II DVD, opens on Michael Bay recalling his 1995 debut: “I remember the day before I was going to direct my little $10,000,000 picture—it was my chance, my one shot—I remember Don Simpson walking into the office with Jerry [Bruckheimer] and he slammed down a 60-page stack of notes, and said, ‘Jerry we’re taking our name off this picture,’ and I saw my whole career go down the toilet on a Sunday afternoon.”

Bruckheimer confirms Bay’s anxieties in an interview immediately following Bay’s recollection: The guy was right to feel the pressure. Bay had to deliver. His burgeoning career depended on it. And eventually he did, the film earning $141 million on a measly $19 million budget, enough of a guarantor to, by Armageddon three years later, see Bay shepherding a $140 million budget. Still, the guy in that 2003 making-of doc is not a guy who has shaken the need to prove himself.

In the 20 years since Bad Boys II, Bay is still proving himself. Five Transformers movies, Pain & Gain, 13 Hours, 6 Underground and AmbuLAnce—each successive title is a testament not to growth or to a broadening of his filmmaking vision, but to compression. To being able to always do more because he’s given more resources based on previously being able to do more based on being given more resources. To trusting in the clarity and strength of his vision, however violent and knuckleheaded and ultimately bleak. To always delivering. To masterful blockbuster pastiche, solidified. Every new Bay, then, is the epitome of Bay—not an experiment or a detour, but the full expression of his talent and influence up until the next chance he gets to do more of the same.

From that primordial stew of self-doubt and furious ambition crawls Bad Boys II, a sequel as Michael Bay’s blown-out manifestation of the unnecessary nature of sequels. Nothing is economic, or subtle, or measured in Bad Boys II—instead, all is mounting spectacle, existing to mount for the sake of mounting. The plot, an excuse to lay the groundwork for ridiculous action scenes upon which Smith and Lawrence can drape their indefatigable charm and improvised banter, is simple: So-called Johnny Tapia (Jordi Mollà), Cuban drug lord and swiss army nemesis, is behind an influx of super-powered ecstasy into Miami. Marcus and Mike, obnoxious motormouth family man and charming playboy psychopath respectively, are on the case, backed by the militarization of the local police department’s Tactical Narcotics Team (TNT). Increasingly complicating the duo’s ability to kill every drug dealer in sight is Marcus’s sister Syd (Gabrielle Union), an undercover DEA agent just recently added to Johnny Tapia’s payroll. Meanwhile, tension between Marcus and Mike escalates as Mike has seemingly learned nothing from their first major adventure, continuing to flagrantly murder people and disrespect the dignity of all living things, dragging Marcus into one mindlessly dangerous situation after another. Mike’s also started dating Syd surreptitiously, a secret Mike knows Marcus won’t take well, however it’s revealed.

It’s the stuff of buddy cop fodder, but pushed to every available extreme. The throughline of Bad Boys is that all cops must be psychopaths to confront a psychopathic world, and that Bay thinks that’s OK. Wasting taxpayer dollars and innocent lives and good taste are the terrible exigencies of the death spiral of modern American life. The only way to respond to such a reality is to meet it on its own terms, blow it to hell, go home, hug your wife and try to sleep one more night, bearing the weight of the many lives you’ve ended.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-