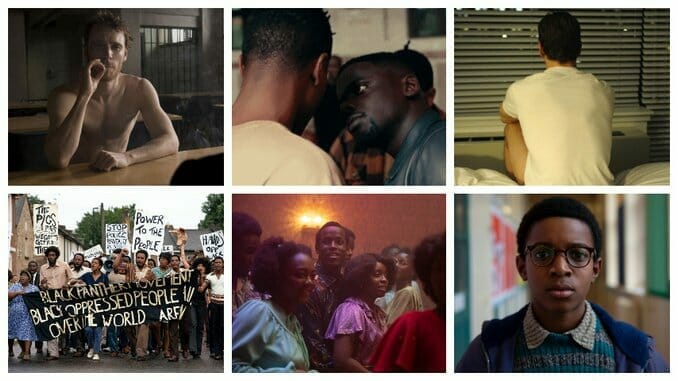

Every Steve McQueen Movie, Ranked

Ranking Steve McQueen movies is a bit like ranking the Seven Wonders of the World: For all that the pyramids of Giza might be more impressive than Machu Picchu, that’s not to say that you are wasting your time hiking the Inca Trail.

McQueen grew up in West London and became an acclaimed artist in the UK before going on to become an internationally renowned director. In 1999 he won the Turner prize, the UK’s biggest art award, and to this day creates celebrated artwork and installations between feature films. He is the first Black filmmaker to win the Academy Award for Best Picture and was knighted for his services to art and film in 2020. Not a man to rest on his laurels, his output is not only exemplary and varied, but produced at an impressive pace, with nine films in the past 12 years—including five as an Amazon Prime anthology collection Small Axe, released all in 2020. His work has been so exceptional that even his worst movies are still, in part, fascinating and hypnotically beautiful.

That being said, after many hours of joyful rewatching and agonizing deliberation, here is every movie by Steve McQueen, ranked:

10. Shame, 2011

McQueen’s second feature and second collaboration with Michael Fassbender is an elegant and raw look at sex addiction that shows off all of McQueen’s style but none of his substance. Fassbender plays a high-functioning sex addict whose life and appearance have a Patrick Bateman-esque sheen of perfection. His sister (a miscast Carey Mulligan) is a melancholy hot mess, dealing with their oft-alluded troubled childhood in a different but equally destructive fashion. For all the moody visuals and dispassionate but stylish nudity, Shame seems disengaged from its subject matter—and aside from an admiration of Fassbender’s, ahem, talents, it’s unclear what any of it is trying to say.

9. Alex Wheatle, 2020

Alex Wheatle is a coming of age story based on the early life of the eponymous award-winning YA author and is the penultimate film of McQueen’s Small Axe collection. Set in the ‘70s and early ‘80s, we follow Alex from his childhood in an orphanage of Dickensian cruelty to his Brixton youth, where he connects with his Blackness, to his being nurtured by a paternalistic Rastafarian cellmate in prison. Alex Wheatle is accomplished and devastating, with dynamic cinematography, a phenomenal soundtrack and a heartbreaking central debut performance from Sheyi Cole. In many ways, it feels like a melding of the other four Small Axe films: The systemic racism of Mangrove, the musical escapism of Lover’s Rock, the daddy issues of Red, White & Blue and the childhood cruelty of Education. But in its thematic overlapping, Alex Wheatle undermines its own significance. It doesn’t have the distinct identity of the other films and, while it’s always a pleasure to watch filmmaking at McQueen’s level, it doesn’t leave a lasting impression.

8. 12 Years a Slave, 2013

This may be a controversially low ranking, as 12 Years a Slave is McQueen’s best-known film, received virtually every accolade it qualified for (including the Academy Award for Best Picture) and set records by appearing on 100 critics’ end of year top-ten lists—taking the top spot in 25 of them. A film of historical significance, 12 Years a Slave is centered around a phenomenal performance from Chiwetel Ejiofor. His tears gently patting down on his daughter’s shoulder belie McQueen’s peerless ability to find rapturous power in moments of silence. But though 12 Years a Slave is McQueen’s most celebrated work, it is also his most conventional. Even the most ardent McQueen fan would fail to spot much of the director’s distinct creative perspective. With the hindsight of his future work, 12 Years feels a little brazen, ticking many of the boxes ascribed to “Oscar Bait.” Most uncomfortable are the accolades that Lupita Nyong’o received for this work; for all the pathos she brings to her feature film debut, it speaks volumes to Hollywood’s love of Black pain that this performance of relentless anguish, brutalization and rape is her best rewarded.

7. Red, White & Blue, 2020

What Red, White & Blue has going for it are two extraordinary performances from John Boyega and Steve Toussaint. Boyega is charming as the fiery and conflicted Leroy Logan, a Black scientist who—following on a racist police attack on his father—decides to join the force to reform it from the inside. His father is played with equally compelling ferocity and dignity by Toussaint. There is so much to love in this film, as McQueen leans into his skill at suspense—ratcheting up the tension with incomparable style—and brings out performances that are able to convey so much without saying a word. However, the script doesn’t match the rest of the film, with clunky exposition and uncharacteristic sentimentality weighing down the actors. At its core, Red, White & Blue is not about police reform. In fact almost all of Logan’s fascinating career accomplishments take place long after the film’s credits roll. Rather, Red, White & Blue is focused on a complicated father/son relationship. Viewed through that lens (and likely through the lens of your own specific paternal hang ups) it soars.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-