The Weekend Watch: Tim Burton’s Hansel and Gretel

Subscriber Exclusive

Welcome to The Weekend Watch, a weekly column focusing on a movie—new, old or somewhere in between, but out either in theaters or on a streaming service near you—worth catching on a cozy Friday night or a lazy Sunday morning. Comments welcome!

Tim Burton’s career has involved more dark circles and spinning spirals than his loopiest designs. He’s always returning to the familiar—and hey, it’s good to have a niche. The goth auteur began his career as a Disney animator, graduating from working on The Fox and the Hound and The Black Cauldron to his own idiosyncratic productions that were a bit too much for Disney to touch. After he left for stints with Pee-Wee, Beetlejuice and Batman, Burton would come back to the Mouse House for his stop-motion Henry Selick collaborations and his Oscar-winning Ed Wood. More years passed, as did another strange phase of Burton’s career. Then he came back for Disney’s ongoing quest to remake all their animated classics as uncomfortably realistic CG hybrids, handling Alice in Wonderland and Dumbo. In a unique turning of the tables, he also did an animated remake of his own live-action short for Disney in Frankenweenie. How often does that happen?

As Burton returns to another old stomping ground with the legacy sequel Beetlejuice Beetlejuice, The Weekend Watch will focus on the first time Burton ventured into live-action (and the first thing of his own that he ever made for Disney): the Disney Channel’s 1983 version of Hansel and Gretel.

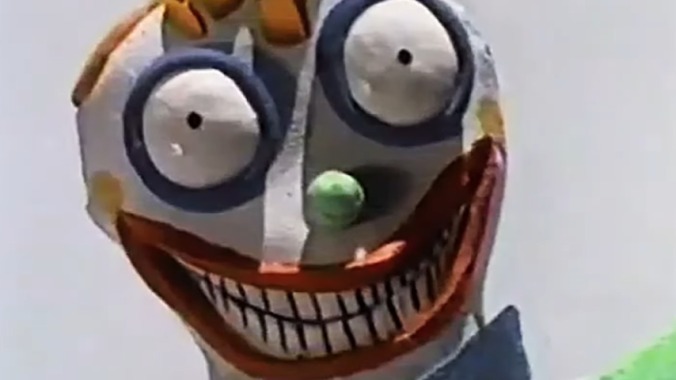

While this 34-minute special only aired a single time on live TV—fittingly, at 10:30 PM on Halloween—it was preserved by intrepid VHS rippers and Burton preservationists; in addition to being easily found on YouTube, Hansel and Gretel screened at the much more prestigious Museum of Modern Art retrospective of Burton’s work. And Hansel and Gretel often feels like a museum piece. The opening, full of recognizable sculptures and warped toys in Burton’s spiky style, is set to Johnny Costa’s piano—a more mature and playfully dissonant edition of Costa’s work on Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. Sharp beaks, extending tongues, Hot Topic stripes and wide-open eyes define the creature-machines outside Hansel (Andy Lee) and Gretel’s (Alison Hong) window. This is immediately, recognizably Burton, even if it’s a made-for-TV movie released years before he ever made a feature.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-